India-Russia oil ties: President Vladimir Putin’s visit for the 23rd India–Russia Annual Summit comes at a time when global power balances are in flux. The meeting signals continuity in a relationship shaped by energy, defence, and strategic alignment. It also reflects the slow movement of the global system toward a more multipolar economic order. The United States remains the world’s largest economy, with GDP of about $30 trillion—roughly 26% of global output in 2024, according to the IMF. Yet Washington’s recent tariff actions and energy sanctions reveal the anxiety created by fast-growing Asian economies and the expanding BRICS grouping.

Energy lies at the heart of this churn. Oil shapes trade flows, security alignments, and the resilience of global value chains. It also defines Russia’s economic strength and India’s import dependency. The policy question is how India can preserve strategic autonomy while securing affordable energy in an uncertain world.

READ | Indian economy: Inflation cools but investment lags

US sanctions and the global oil disruption

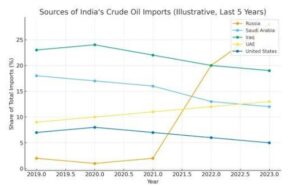

The United States has long used energy policy as an instrument of geopolitical pressure. Russia produces about 10% of global crude, behind the US and Saudi Arabia. China, India, Turkey, and the European Union have been among its core buyers. The first sanctions wave came in early 2022. The Biden administration banned Russian oil imports.

The G7 introduced a price cap in December 2022. Russia responded with steep discounts, offering crude at $30–35 per barrel below Brent, which India imported on economic grounds.

Sanctions tightened again in October 2025, when the US Treasury targeted Rosneft and Lukoil and their subsidiaries, firms responsible for nearly half of Russia’s oil output. The action narrowed discounts and constrained trade, forcing importers—including India—to reassess long-term supply strategies.

Geography and economics of oil production

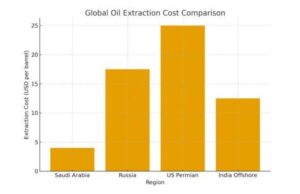

Oil extraction remains highly uneven across geographies. The Middle East holds the world’s largest reserves. Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar field, stretching roughly 280 km, produces crude at $3–5 per barrel because of simple geology and favourable reservoir pressure, according to the IEA.

Russia’s West Siberian Basin covers 2.2 million sq km and is the largest hydrocarbon basin in the world. But its extreme climate drives extraction costs to $15–20 per barrel, reducing flexibility under sanctions.

The United States has the prolific Permian Basin. South America adds supply from Venezuela, Brazil, and Argentina. India has modest offshore reserves in Mumbai High, the KG Basin, and the Barmer block, but rising energy demand far outpaces domestic production.

India is the world’s fourth-largest refiner, with major complexes run by Reliance (Jamnagar), Nayara (Vadinar), and public-sector units under Indian Oil Corporation. The scale makes India an important player in global petroleum markets even without large domestic reserves.

India-Russia oil ties: A long strategic partnership

India–Russia ties are anchored in decades of cooperation. The Soviet Union’s influence shaped India’s early economic thinking, including the shift toward state-led industrialisation and centralised planning under the Five-Year Plans.

The 1971 Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation deepened cooperation across defence, space, heavy machinery, and energy. Russia remains central to India’s defence inventory and its civil nuclear expansion, including the Kudankulam reactors built with Russian assistance.

Coordination in multilateral forums such as BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the United Nations underscores the persistence of strategic alignment even as both economies engage widely with other global partners.

A resilient, diversified energy strategy

India’s economic growth target—becoming a developed economy by 2047—will require secure, affordable, and diversified energy supplies. Oil still accounts for 28% of India’s primary energy demand, according to BP’s Energy Outlook.

The policy priority is to reduce dependence on a narrow set of suppliers without compromising energy security. This requires: expanding domestic exploration and production; raising refinery efficiency and upgrading technology; scaling renewable energy, including green hydrogen, biofuels, and electric mobility; diversifying long-term crude contracts across Africa, Latin America, and West Asia; and using strategic reserves and forward contracts to manage global price. volatility.

India has managed the Russia energy shock with relative stability. But future resilience depends on how well the country builds alternatives that align with climate goals, industrial needs, and geopolitical realities.

India–Russia energy ties sit within a wider shift toward multipolarity in the global economy. The task ahead is not to choose sides but to ensure that energy security, economic efficiency, and strategic autonomy reinforce each other. A diversified energy portfolio and steady investment in low-carbon technologies will offer India the policy room needed in a fractured world.

Swati Mehta is Associate Professor, Punjab School of Economics, GNDU, Amritsar.

Dr Charan Sigh is a Delhi-based economist. He is the chief executive of EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank, and former Non Executive Chairman of Punjab & Sind Bank. He has served as RBI Chair professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.