By Sucheta Sardar and Sanghamitra Kanjilal Bhaduri

Unemployment, uncertainty among Indian youth: There is immense potential for economic and social progress in countries that take advantage of their demographic dividend. But this potential will remain unrealised without planning and investment to help the youth achieve their aspirations. India has the largest adolescent and young people (AYP) population in the world.

According to Census 2011, every fifth person in India is an adolescent (10-19 years), totalling a mammoth 236.5 million (19.2% of the country’s population). Also, every third person is a young person (10-24 years), numbering 229 million. Yet ground level research on the challenges faced by the youth and policy prescriptions to mitigate them are absent. Young people’s lives are shaped by the major transitions they make — moving from primary to secondary school, leaving school, starting work, and marriage and motherhood in the case of girls. The adolescent population has specific health and developmental needs.

Due to the existent social paradigm in India, young people tend to have many family responsibilities. This calls for a need to better understand the everyday realities of young people’s lives, as their health and well-being tend to be affected by cultural, socio-economic and environmental risk factors. It is important to link all these aspects of young people’s lives, rather than focusing on each in isolation.

There is need to take a holistic view of all the factors that shape young people’s lives. This would enable to build a powerful multidimensional picture of the challenges and opportunities facing young people and make targeted investment to improve their well-being and productivity. There is also a need to reach them through the use of mobile phones, social media and community-based strategies. Interactive surveys and data-collection methods should be used to build an accurate scenario of the forces shaping young people’s lives and to guide them to negotiate the problems they face.

READ I Women bear the brunt of job losses as Covid-19 devastates Indian economy

Poverty, unemployment make youth vulnerable

Eradicating poverty (SDG1) is a particularly pertinent youth issue, as a majority of those aged 15-24 are likely to be among the working poor. Globally 16% of all employed youth were living below the poverty line in 2015, compared with 9% of working adults . Society pays a high cost when development policies and programmes fail to take cognizance of the needs and aspirations of the youth. For example, lack of social protection and job security make youth vulnerable.

In such a situation the impact of poverty is not only humongous, but also multi-dimensional and long-lasting and often inter-generational. Employment opportunities get narrowed for those dropping out of school and poor nutrition during adolescence often leaves chronic effects on the health of individuals when they become adults, affecting labour productivity.

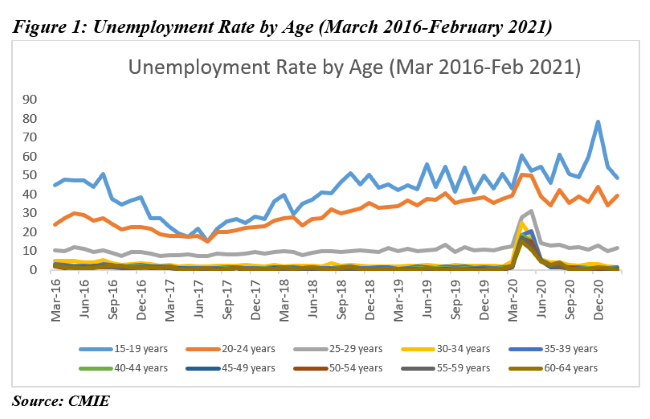

CMIE monthly data on employment for the period from March 2016 to February 2021 shows that unemployment rate (those who are seeking jobs, but not getting) is highest among the youth. This is a consistent trend with 15–19-year-olds being most impacted, followed by 20–24-year-olds as seen in Figure 1.

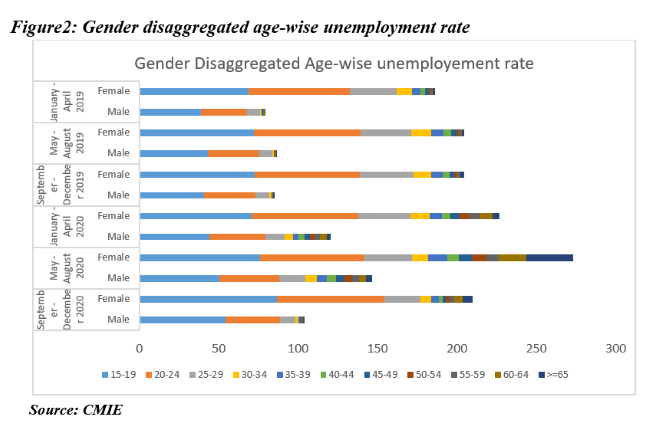

Gender disaggregated data, represented in Figure 2, shows a similar scenario faced by males and females. Both male and female unemployment rate is highest in this age group with young females facing a greater brunt. Increased educational enrolment, early marriage, child bearing and participation in domestic chores are cited as the most important reasons explaining the phenomenon of higher unemployment rates among young girls and women aged 15-24 years. The pandemic too impacted this group the most with highest job losses occurring among the youths and consequently a slow recovery and low chances of them getting jobs back.

READ I Covid-19: Multilateralism, diplomacy can improve pandemic response

Unemployment and uncertainty in jobs

Young people are crucial stakeholders in the pursuit of decent and productive work for all (SDG 8). The transition of young people from schools and training institutions into the labour market is a phase marking a critical period in their life cycle. However, very often, their positive and negative experiences and viewpoints never get shared with decision makers and their voices remain unheard.

Young people are often trained for skills, which are not matched by labour demands. This leaves many young people stuck in unemployment with their rates of unemployment being significantly higher than that for the adults as seen in Figure 2 and with higher uncertainty as well. When they do get employed, youth often end up working in vulnerable conditions foregoing job security, minimum wage and with limited or no access to legal benefits as an employee.

Creating opportunities for youth to move out of poverty into decent and sustainable work will help capitalize on the demographic dividend created by India’s youthful population . Given this situation, youth will not only directly experience the outcome of plans to attain SDGs, but will also be the key driver for their successful implementation .

Most of the government programmes for youth fail to understand what drives the behaviour in the first place, and ignore the broader risks that young people face from poverty, work, social stigma or exclusion from quality services. Better research tools and more community-based initiatives are needed that focus specifically on understanding and enhancing resilience among adolescents. There should be evidence-based understanding of the factors that matter most, and this can inform the timing and focus of policies and interventions needed to support positive transitions for adolescent girls and boys.

It is essential to deploy a bottom-up approach in which adolescents are treated as partners in improving their health and well-being, not just the recipients of change. Young people can create a dynamic force of political change and social transformation when they are included in decision-making processes. Interventions need to be made within the communities and across all settings to understand how young people spend their time, how they access resources and who controls their earnings.

READ I Fertilizer policy 2021: Modi government faces Hobson’s choice on price hikes

Investment in human capital the highest priority

Human capital formation is the foundation for the transformation of the AYPs in leading a decent life. Improving quality of schooling, sharing information on employment opportunities after schooling and about accessing opportunities including the scope for skill formation to be more suitable for employment through regular counselling at school may help to generate a positive cycle of thinking and pursuing education. School-to-work transition techniques need to be focused upon. This will help reduce the number of NEETs (Not in Education, Employment and Training) among the youth.

AYPs need higher skills to have better employment potential and bargaining power. Being mostly in informal sector, they have little scope to bargain and, therefore, they need to be oriented towards the benefits available for the unorganised labourers. To cope with their vulnerability there is a need to encourage them to develop a habit of saving and to be able to avail of social protection schemes like Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana/ Public Provident Funds. Most effective steps in capitalising the potential of adolescents in India include generating better education, skill development, work and citizenship opportunities for adolescent girls and boys.

(Sucheta Sardar is Assistant Professor, Sharda University. Sanghamitra Kanjilal Bhaduri is a post-doctoral scholar, Department of Economics, University of Algarve, Portugal.)