The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 by the World Economic Forum reveals a dramatic fall in employment opportunities because of COVID-19 pandemic. The report shows that job losses are more pronounced for women than men across the globe. The report says the pandemic has set the world back by a generation and it will take several years to close the gender gap in economic participation.

India stood at 140th position out of 156 countries in gender parity on the Global Gender Gap Index (a fall of 28 places compared with last year). In terms of economic participation and opportunities, India is placed abysmally low at 151. It fares only slightly better than countries such as Pakistan, Syria, Yemen, Iraq and Afghanistan that are at the bottom of the list.

This low rank is because India has recorded one of the lowest women labour force participation rates (LFPR) in the world in 2018-19. The recently released Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) quarterly report (April-June, 2020) indicates a further decline by 8% compared with the same period last year. The first official labour force survey report in the post lockdown phase echoes the findings of the Consumer Pyramid Household Survey (CPHS) data collated by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) regarding the impact of the lockdown on headline employment indicators.

READ I Agrarian crisis: FPOs is the way out for Indian farmers

Economic crisis, job losses expose gender gap

According to the CMIE data, when India was experiencing 6% economic growth between 2016-17 to 2019-20, total employment declined from 413 million to 409 million and this fall was triggered by a fall in women’s employment from 54 million to 44 million. During the same period, men’s employment rose from 359 million to 365 million, clearly indicating the gender gap. This decline in workforce participation rate is also validated by the Employment and Unemployment Surveys of the National Sample Survey and by Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data that shows a fall in workforce participation from 21.9% in 2011-12 to 17.6% in 2018-19.

While India was already grappling with low women WPR before the pandemic, the sudden decision of the Union government to impose a nationwide lockdown (index value=100) made the chances of women joining the labour force even worse. The lockdown was declared only the evening before it came into force. Like other pandemics, the impact of COVID-19 is not gender-neutral and women bear the brunt of the outbreak. During the strict lockdown phase between March and June 2020, the employment rate of women declined from 8.9% to 6.7%. The rate for men fell from 66% to 53% during the period.

Though job losses were observed in both rural and urban areas, for women, the recovery in the post lockdown period in urban areas was almost nil compared with men, for whom the recovery rate was from 49.4% to 60.4%. The unemployment rate for women also rose almost by 5 percentage points during the lockdown period and this is much more than the same quarter in the previous year when it was 7.1% in urban areas.

The recently released quarterly bulletin of PLFS also shows a significant rise in women’s unemployment from 10% in Jan-Mar 2020 to 21% in Apr-Jun 2020. These results indicate that the relative fall in employment was greater for women, compared with their pre-pandemic level. Job revival was not gender-neutral even during the post-lockdown phase.

READ I ADB predicts 11% growth for Indian economy, sees benign inflation

Heavy job losses in manufacturing, services

The existing literature shows a greater impact of the pandemic in urban areas of India. As per Deshpande (2020), there was a 33% drop in employment in urban areas compared with 29% in rural areas. This is connected to the closure of the manufacturing and services firms and a significant percentage of workers are employed in these two industries in urban areas. The gendered difference in this case was revealed by the PLFS bulletin that shows steeper decline for women in the secondary sector during the lockdown period.

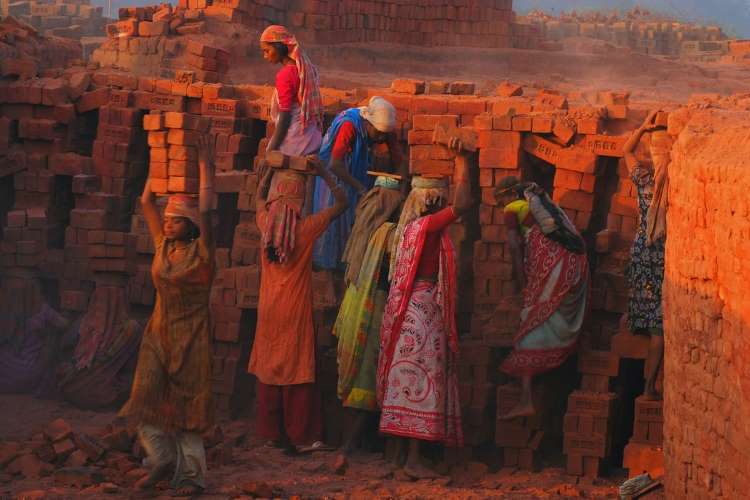

In the pre-lockdown quarter (January-March, 2020), 34% of women were engaged in the secondary sector, which fell to 24% in the next quarter (April-June, 2020). It is historically true that women in the secondary sector are mostly engaged in the manufacturing sector. The CMIE data also show the same trend of falling overall manufacturing employment in urban areas during the lockdown and post lockdown phase from 16.7% in March 2020 to 10% in September 2020. There is revival of 13% in December 2020. The CMIE data has shown the slow pace of recovery of employment in the economy in the post lockdown period.

Most of the job losses were among the younger sections than the older. Approximately 59% of the workers in the 15-29 age group lost jobs during the lockdown and the post lockdown period which is not more than 40% for older age groups (Abraham, et al. (2021). Moreover, the CMIE data depicts a declining employment rate for all education categories over the years.

A detailed look at the monthly data shows the fall in the employment rate in the lockdown and the post-lockdown phases. Despite a revival, employment has not reached the level of December 2020 and is consistent across all education levels. Individuals with lower education levels were found to be more affected by the lockdown measures in comparison to better educated groups. Moreover, the informal sector workers also suffered more severe job loss.

Participation of individuals in the workforce varies for different social groups and hence there was a differential impact of pandemic across social groups. The fall in employment rate was the highest for Scheduled Tribes (ST), followed by Scheduled Castes (SC) and the rate of revival in jobs was also the lowest for the former in the post-lockdown period. The unemployment rate only increased from 11% to 15% for the Upper Castes.

For the STs and SCs, it increased from 8% to approximately 23%. Abraham et. al (2021) mention that even if there is a revival of jobs, the pattern and the level of jobs were not matched by the previous level. Moreover, there has been a shift of workers from regular salaried employment to self-employment.

READ I Fertilizer policy 2021: Modi government faces Hobson’s choice on price hikes

MSME crisis triggers massive job losses

The decline in all categories of work is also evident from the PLFS quarterly bulletin for both men and women between Jan-Mar 2020 and April-Jun 2020. This decline is evident because of the shutdown of small businesses, other manufacturing and service sector units. The shutting down of small businesses affected women workers more as their employment in this was largely necessity driven.

The restrictions on the entry of domestic helps in houses due to the lockdown affected their regular work and women working as casual labourers in various units also faces the same problems. Thus, the proportion of self-employed women declined to 5% in Apr-June 2020 quarter from 6.7% in the previous quarter. The fall in regular wage work among women declined by 1.7 percentage points.

The above analysis and the existing literature related to the condition of employment in the pre- and post-lockdown period emphasize that the impact of the lockdown is more pronounced in urban areas than in rural areas. The recent quarterly bulletin of PLFS and the CMIE data are mostly urban biased. Hence this paper will also focus on the employment condition in the pre-lockdown and post-lockdown period in urban areas.

Existing literature has examined the effect of the lockdown on overall employment in India, mostly by either using micro assessment studies or by the CMIE data. The present study, for the first time, attempts to analyse the magnitude and nature of job revival and the consequent fall in unemployment across gender and state. The study uses both the official surveys and CMIE data.

The study concludes that more direct employment generation through increased public investment and provision of public services is highly recommended along with further reservation for women as a stop-gap solution. Strengthening access to social protection, with a focus on old-age pensions and healthcare in all sectors including those where women are concentrated, is the need of the hour.

(Priyanka Chatterjee is Assistant Professor at Sharda University, Greater Noida. Shiney Chakraborty is Research Analyst at Institute of Social Studies Trust, New Delhi.)