By Bijulal MV

The nationwide lockdown announced by the government has forced many education institutions to adopt online teaching. Remote learning is now touted as the new normal for all levels of education — from post-graduate level to kindergarten. The NCERT has created an online academic calendar for school children in the country, while the Central Board of Secondary Education has urged schools to engage children through videoconferencing apps. The University Grants Commission has constituted a committee to recommend ways to increase online academic transactions in universities. The government is keen to promote online learning as it will reduce the education budget considerably. But, is the country ready to take the plunge?

Online learning is catching up and the number of students using digital platforms is growing at a fast clip. This has led to an exponential growth in allocations for online education, which is emerging as an alternative to person-to-person contact learning. The discourse on the subject is projecting a conventional vs modern binary. The problem with the “modern” mode is that it is failing to sustain the levels of inclusiveness and social justice offered by classroom teaching. The call for a shift to remote learning is capturing the public imagination. One has to assess the impact of this new normal on the fundamental principles of equality and the right to livelihood of a large number of people before deciding the desirability of online learning in the country.

READ: Great lockdown: Remote working widens India’s digital divide

READ: Coronavirus pandemic exposes India’s online teaching prowess

A fundamental disconnect, that can be called data ability, exists between students and teachers engaged in an online interactive platform. Data ability is the sum total of various factors — economic, infrastructural cultural, geographic and social – that inhibit the equitable and effective use of remote learning platforms. This article draws heavily from the author’s experience as a teacher at the university level.

The lockdown has pushed India’s poor into abject poverty while moving its strong middle class into the throes of poverty. Survival is an issue for a large number of Indians at present. The question is how could a family invest in an online learning environment in the prevailing circumstances. The proponents of the idea of online education as the new normal betray their ignorance of its social impact.

READ: Can India match Chinese success in post-Covid global economy?

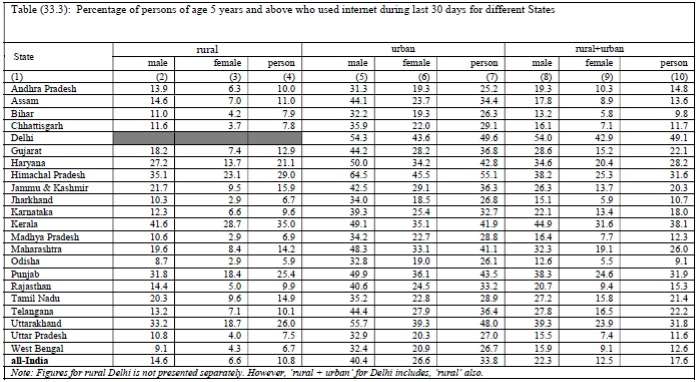

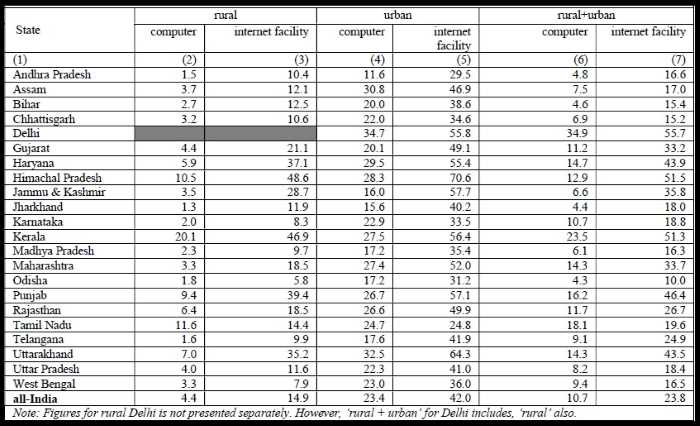

The economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is yet to be ascertained fully. Questions are still unanswered on whether it right to promote remote learning in a low middle-income country like India when some of the richest nations are unable to roll out such a system effectively. Findings of the NSS 75th Round Report released on November 23, 2019, offer an unambiguous response on this issue. The report shows only 10.7% of the households have a computer — 4.4% in rural and 24.4% in urban areas. In spite of the proliferation of smartphones, just about 24% of Indian households have internet access – around 15% in rural and 42% in urban areas. Another disabling factor for online learning is the computer proficiency of the population which is below 50% even among urban population.

The author’s personal experience with remote teaching of post graduate courses in the last few weeks explains the issue from a different perspective. The group of students in question has access to computers – 50% of them have own equipment while the rest have access through friends. It was found that environment-related factors as well as economic factors (empirical verification is difficult) affected the conduct of classes. One needs to understand that the experience occurred in Kerala where the access to computers and internet usage are high compared with the national average. The key learning from the experience is that a well thought out learning plan that takes into account all factors that influence equitable access is a primary requirement for the success of remote learning experience. If the students are unable to raise the fundamental questions related to the digital divide and data ability, remote learning process will only lead to the widening of the inequality among the different sections of the society.

Internet users during last 30 days (%)

READ: Make PDS more inclusive, give ration cards pan-India validity

Education is a basic human right. The introduction of remote teaching raises a few questions related to the right to education. Such actions cannot progress without the meaningful participation of marginalized communities. Right to development needs to be facilitated through an interconnected series of enabling programmes and the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution provides a basis for inclusive governance. The right of people to have access to free and quality education in an equitable manner cannot be ignored while introducing new platforms of learning. A section of critics argue that the introduction of a new platform may help sections of privileged people, resulting in perpetuation and widening of the digital divide.

Concerns about the digital divide were highlighted by the most recent advisories from the UNESCO and the UNICEF. The Futures of Education commission, a body that has experts from several countries including India, says the digital mode of education will deepen inequalities world over, and more so in poor countries. Its suggestions are highly relevant to India, considering the levels of digital divide that exist in the country. Experts have already highlighted the stress on families affected by joblessness, fall in income and other difficulties. As government agencies such as NCERT, CBSE and UGC push for online education, they should also study the preparedness of various stakeholders. Democratic decision making requires consultative governance and convergence of ideas. Any model that follows a trickle-down approach is bound to fail.

Access to computer, internet connection

READ: Coronavirus crisis: Why not a salary challenge at the national level?

Digitising education at the elementary level will result in long-term problems that will accelerate social exclusion and geographic divide across India. The Right to Education Act, 2009 had identified several important interventions by agencies of state to improve teaching and learning facilities and health infrastructure. According to an Oxfarm study (2019) on the implementation of RTE, all indicators pointed to severe lapses on all these objectives. Adding to these, discrimination based on caste, religion and sex is still rampant in most parts of the country. This being the case of progress in measures to strengthen social and cultural impact of school education, a systemic intervention to promote data-related infrastructure could create a systemic logic to cover up the mismanagement of initiatives to improve social justice and equitable distribution of quality education. In remote learning, each student will be a user of the services, where there is no guarantee of steady supply of data at affordable rates.

The governments, both at the Centre and states, must address some fundamental questions to ensure democratic governance of online learning. The implementing agencies must ensure fair and equal access to education to all Indians. If a majority of citizens are deprived due to official apathy, it will result in the perpetuation of inequality between geographies, castes and communities. There is also a need to ensure the security of participating students according to the national Information technology policy. The government and its agencies should not turn a blind eye to the stark reality of digital divide, evident in the statistics collected by its own agencies.

(Dr Bijulal MV teaches at the school of international relations and politics at Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam. Shambhu Ghatak’s support in preparing the table is thankfully acknowledged.)