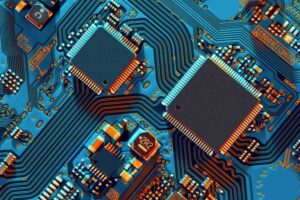

Semiconductors have become the nerve centre of global technology competition. India, keen not to be left behind, is preparing the second phase of its India Semiconductor Mission (ISM), with a budget of $15 billion (₹1.3 trillion). Unlike the first phase, which focused on chip fabrication and assembly plants, the new push is aimed at micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). The goal is to develop local suppliers of high-purity silicon, photoresists, and specialty gases—materials that make the industry tick.

This is a marked shift in strategy. Phase one concentrated on attracting global names to set up fabrication units and outsourced semiconductor assembly and testing (OSAT) facilities. Phase two seeks to ensure that small firms become reliable suppliers in the global value chain, reducing India’s dependence on imports. Industry analysts project the semiconductor market to touch $1 trillion by 2030, and the government wants domestic firms to claim a share.

READ | India resets China ties at SCO Summit 2025

Semiconductor mission: Building the ecosystem

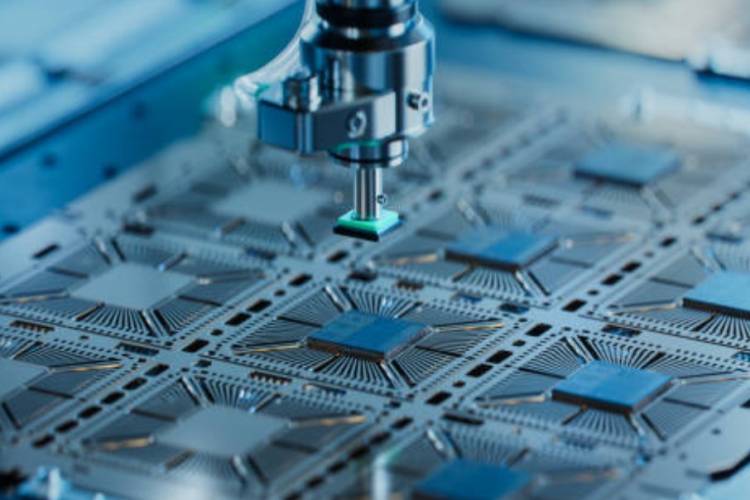

Making a chip involves hundreds of steps, each requiring precision and materials of exacting quality. By incentivising MSMEs to meet these needs, India hopes to build a self-reliant ecosystem. Officials indicate that the government is also weighing proposals to extend incentives for research, development, and skill-building, which could further sweeten the pitch for foreign investors.

A revamped Design Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme is also on the table. Many Indian startups in chip design struggle to progress beyond Technology Readiness Level 7 (TRL-7) because of funding gaps. As a result, they are acquired prematurely by larger firms at low valuations. The reworked scheme aims to provide financial and technical support to help these startups scale globally.

What did phase I achieve

The first phase, launched with ₹78,000 crore, has already approved 10 projects: two fabrication units and eight OSAT/ATMP facilities across Gujarat, Assam, Punjab, and Andhra Pradesh. Micron Technology’s $2.75 billion ATMP unit in Sanand and Tata Electronics’ fab in Dholera, capable of producing 50,000 wafers a month, stand out.

Just this month, four more projects were cleared: SiCSem and 3D Glass Solutions in Odisha, Continental Device India (CDIL) in Punjab, and Advanced System in Package (ASIP) Technologies in Andhra Pradesh. The 3D Glass Solutions plant in Bhubaneswar has attracted backing from Lockheed Martin, Intel, and Applied Materials—a sign of growing global confidence.

Geographic spread and global context

The spread of projects across Gujarat, Assam, Punjab, and Odisha reflects an effort to disperse economic benefits and avoid concentration in one region. Sanand and Dholera are shaping up as semiconductor hubs, while Mohali and Guwahati are emerging as important nodes.

Globally, the industry has been buffeted by pandemic disruptions and geopolitical rivalries. In response, the US, China, and the EU have announced over $200 billion in support for domestic production. India’s ISM is part of this worldwide race to secure semiconductor supply chains.

India’s advantages and challenges

India brings a large engineering talent pool, a growing electronics market—valued at $155 billion in 2024 and expected to reach $300 billion by 2030—and policies designed to improve the ease of doing business. Demand from smartphones, electric vehicles, and renewable energy systems will ensure a ready market for chips.

But hurdles remain. Semiconductor manufacturing is capital-intensive and technology-heavy, demanding skills that India must build at scale. Success will depend on efficient policy implementation, minimal bureaucratic friction, and sustained investment in education and training.

If the second phase of the ISM delivers, India could move closer to its ambition of becoming a global semiconductor powerhouse. By empowering MSMEs and startups, the government is not only strengthening its industrial base but also laying the foundation for technological sovereignty in an era when semiconductors decide both economic competitiveness and strategic security.