GST reforms: India is preparing for a significant overhaul of the goods and services tax to simplify the regime. The proposal on the table is a two-slab structure of 5% and 18%, with a special 40% rate reserved for sin and demerit goods. While the change promises simplicity, it has triggered sharp resistance from state governments which fear losing Rs 7,000–9,000 crore annually. Their anxiety is not misplaced.

For most states, GST is the lifeline of public finance. It contributes nearly 23% of provisional revenue receipts and accounts for about 44% of their own tax revenue in FY25. Nearly 45% of states’ own tax revenue comes from State GST (SGST), with Bihar, Gujarat, West Bengal, Karnataka, and Uttarakhand most exposed to changes. In contrast, states such as Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Telangana rely less on SGST, but they too stand to lose.

READ | Deepwater exploration at the core of India’s energy push

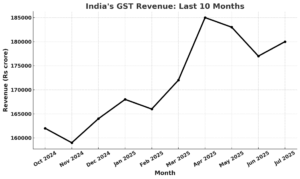

The concern is magnified by slowing goods and services tax revenue growth. Collections are projected to rise by just 8%, compared with the 14% annual growth before GST’s launch in 2017 and 11.6% in 2019. For states already grappling with fiscal constraints, such a slowdown imperils their ability to finance education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

Risk of revenue erosion

The crux of the problem lies in moving big-ticket items — automobiles, cement, and white goods — from the 28% bracket to 18%. These categories form the bulk of goods and services tax collections for most states. Lowering rates would certainly make goods cheaper and boost consumption, but it also risks creating a fiscal hole that states cannot easily bridge. The overall annual shortfall could exceed Rs 1.1 trillion, or 0.3–0.4% of GDP.

The GST Council has to balance the promise of higher consumption against the certainty of immediate revenue loss. Without a cushion, the reforms may weaken states’ fiscal position and compromise development spending.

Compensation and transitional support

One option is to extend the GST Compensation Cess beyond its expiry in March 2026. Originally designed to guarantee states 14% annual revenue growth, the cess has been an effective safety net. A reimagined cess, levied on a wider range of high-value goods, could provide a steady stream of funds without unduly burdening consumers.

Another possibility is a temporary revenue protection mechanism. Guaranteeing states a baseline growth of 10–12% for two to three years post-reform would ease the transition. Surplus cess collections could be used to partially offset the projected shortfall.

Over the medium term, the government must consider bringing petroleum, alcohol, and real estate under the GST net. These sectors are major contributors to state revenues and their inclusion could significantly strengthen the tax base. Expanding goods and services tax coverage would improve revenue without raising rates, offering a more durable solution than repeated compensations.

Rethinking revenue sharing

The revenue-sharing model itself warrants review. Currently, states get 100% of SGST, about half of Integrated GST (IGST), and a portion of Central GST as recommended by the Finance Commission. Industrialised states such as Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, which contribute heavily to GST collections but lose out under consumption-based taxation, have long sought a more equitable formula. Adjusting IGST apportionment or revising devolution criteria could create a fairer fiscal balance.

A related concern is whether tax cuts genuinely benefit consumers. Past experience suggests otherwise. For instance, reductions on white goods often translated into price cuts of barely Rs 1,000, with much of the benefit absorbed by manufacturers. A price-monitoring mechanism, backed by penalties for non-compliance, could ensure that lower rates feed through to consumers. Targeted tax credits or subsidies for labour-intensive sectors like textiles could further boost employment while supporting states such as Gujarat and Tamil Nadu.

GST reform: State-specific concerns

Not all states face the same pressures. High-population states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which carry heavy developmental burdens, will need greater central support. Increased grants or retention of lower rates for state-specific sectors—such as textiles in Tamil Nadu or diamonds in Gujarat—could minimise disruption.

In the long run, a simplified GST structure should reduce compliance costs, spur consumption, and enhance tax buoyancy. But the immediate risks are real. Unless supported by compensatory mechanisms and flexible revenue-sharing arrangements, the reforms could weaken states’ finances instead of strengthening them.

The goods and services tax overhaul is a bold reform in search of simplicity. But simplification should not come at the cost of fiscal fragility in the states. Extending compensation, broadening the base, recalibrating revenue sharing, and ensuring consumer benefits are critical to success. Unless the Centre treads carefully, the promise of a consumer-friendly GST could end up undermining the very developmental aspirations that depend on strong state finances.