By Sadhika Tiwari

On March 19, 2020, Lakhan Sabar, 35, a farmer who lives in Boro village of drought-prone Purulia district of West Bengal, had to sell two quintals of his cucumber crop at Rs 900 per quintal because no vehicles were available due to the COVID-19 lockdown to take his produce to market, where he could have got a higher price of up to Rs 2,000 per quintal. His total produce this season was around eight quintals; the remaining six quintals found no buyer and were left to rot.

In the weeks before the pandemic struck, when it was sowing season, he had taken a loan of Rs 20,000 from the local cooperative bank in Boro village in Purulia at 12% rate of interest and Rs 10,000 from a local money lender to sow the crop a few months back. The rate of interest from the local money lenders is so high that the interest often grows up to 80% of the principal amount within five months, Sabar said.

Sabar grows tomatoes, cucumbers and watermelons. His last sold crop was tomatoes, after which he was relying on the cucumber harvest to repay his loans. “I managed to save some money by selling tomatoes. That is what we were using so far,” Sabar said in a webinar conducted by Praxis India, a Delhi-based non-profit, on April 10, 2020. “How will I repay these loans? I sold a goat to pay off some of my debt. My family survives on whatever we earn from our agricultural produce,” said Sabar who has a family of five to sustain.

READ: Covid-19: How Kerala fought the deadly virus

Amid the countrywide lockdown due to COVID-19, farmers and daily-wage earners belonging to the denotified Kheria Sabar tribe in Purulia district of West Bengal are struggling for sustenance, a survey of 33 villagers from 30 districts in Purulia district of West Bengal found.

Direct cash transfers, free ration and subsidies that the government had announced have not reached many. The few who have received some help from the government have found it to be insufficient.

Denotified tribes were listed as criminal tribes during British rule under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. They were delisted or ‘denotified’ in 1952; despite this, they continue to face stigma because of their status as erstwhile criminal tribes. Denotified tribes are scattered across India and often migrate from one state to another, engaging in various occupations such as farming, domestic work and salt trading. Many also work as acrobats, street dancers, snake charmers and pastoralists.

India has 1,500 nomadic and semi-nomadic tribes and 198 denotified tribes, said the Renke Commission report of 2008, emphasising that denotified tribes continue to face poverty and marginalisation and are one of India’s most backward tribes. The report found that these tribes continue to fare poorly in literacy, housing, employment and living conditions, with 89% of these tribals being landless.

READ: Govt agencies push online learning, disregard official data

Survey findings

Most daily-wage earners had not received their wages and indebtedness has increased post-lockdown to a level that could push them into bonded labour, the survey, conducted between April 4 and April 6, 2020, by Praxis India and the National Alliance Group for Denotified, Semi-Nomadic and Nomadic Tribes (NAG-DNT), based out of New Delhi, found. Most villagers do not have a Jan Dhan account and the few who do, have either not received any relief money from the government or said they found it too meagre to sustain their families.

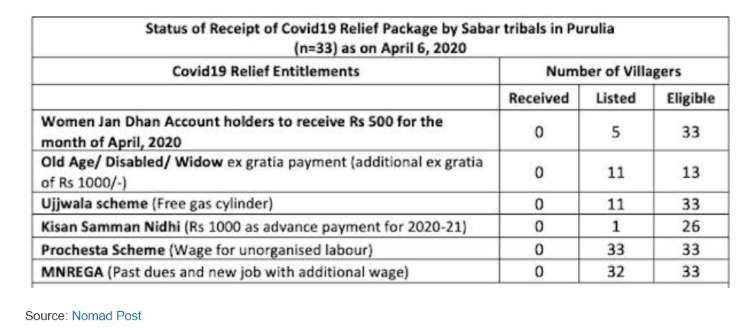

Other government measures of providing relief to poor families through schemes including pension schemes under the National Social Assistance Programme (monthly pensions for senior citizens, widows and differently-abled), Ujjwala scheme (subsidised cooking gas cylinders), Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme (annual payment of Rs 6,000 to farmers), Prochesta scheme (monetary assistance for daily wage labourers during the lockdown in West Bengal) or Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS, 100 days’ paid work in rural areas) are not able to bring any major respite to these families, the survey report, titled ‘Analysis Report Of Information Collected From DNT Workers in Purulia, West Bengal During The COVID-19 Lockdown’, found.

Alleging discrimination from the community and the administration, the report recommended that a local community organisation be appointed as a nodal point to disburse relief and ensure it reaches the tribes, and that the government look into alleviating indebtedness.

After the National Alliance Group for DNT reached out to the district authorities with these suggestions, the district collector of Purulia appointed the ADM as the nodal officer to disburse relief to the community.

“Stigmatisation might increase as hunger might drive one or two people into thieving, which would affect the entire community; there is also an increased fear of lynching,” said Prasanta Rakhshit, 60, who has been working with Kheria Sabar community for 37 years and is associated with the Paschim Banga Kheria Sabar Kalyan Samity (PBKSKS) in Purulia, West Bengal and was a part of the survey team.

READ: Make PDS more inclusive, give ration cards pan-India validity

Increasing indebtedness

The survey showed that most of the Sabar families are daily-wage earners and none of them had received any wages as of April 6, 2020, despite the prime minister’s appeal to the employers to pay salaries to all workers during the lockdown, “this does not seem to be happening anywhere here”, the report reveals.

Contractual labourers who had been working in different states have returned to their villages during the lockdown. “It is not easy for any family to survive without income,” said the report as most of these labourers have meagre savings and many haven’t even received their wages for the previous week.

“I used to get Rs 220 and 2 kg rice as a daily wage but that has stopped during the lockdown,” said Phulmoni, 40, who lives in Purulia and works as a daily wage labourer in West Bengal’s Bardhaman district. She is finding it hard to sustain her family as her wages have stopped and shopkeepers have stopped giving things on credit or loan. “I am getting rice from the ration once a week, but that is hardly enough for the family,” she said.

Of the 33 tribals surveyed, nine of them (27%) had already taken a loan during the lockdown period. The most common reason for these loans was found to be access to food, especially for children.

Of the nine people who took a loan, at least one took the loan from his employer, which indicates a higher possibility of the worker getting into a bondage situation, the report said. “Indebtedness has always been a trigger for other social and economic exploitation, causing a rise in trafficking, bonded labour and child labour,” it said.

Families who have taken land on lease have to pay a monthly rent. These farmers will either have their loans deferred leading to its accumulation or will have to take loans from the local moneylender.

“I grow vegetables like tomatoes, gourds, beans, cauliflower, cabbage, watermelon, etc. twice a year,” said Kharu Sabar, 52, from Manbajar block, Purulia district. “I spent almost Rs 64,000 on my crops but have recovered only Rs 10,000 so far. I recently earned Rs 800 from selling beans. I don’t know how [I will] sell vegetables that are already planted and ready for harvest.”

Seven of the 33 people, about 21%, had at least one family member who was ill, adding the costs for medicines to the expense. Three of these seven families had to take a loan.

In about two weeks, the number of families taking loans could increase drastically, which is a worrying trend because these loans were become increasingly important for food and healthcare. “At the current rate, there is scope for a high increase in bonded labour, given that workers will either turn to moneylenders or employer to borrow,” found the report.

Loss of land and livestock are also a worry during the lockdown as these are the first to be sold or mortgaged for loans and have been hard for the community to acquire. The Sabars were given ‘patta’ land by the government which “will gradually go away from their hands as they will end up illegally mortgaging it for loan”, said Rakhshit from PBKSKS, “There will also be a loss of livestock as there will be increased distress selling to cope with lack of income.”

After the survey was conducted, the local authorities permitted the farmers to sell their produce in the market, “but by now the entire lot for several vegetables like cucumber has already rotted, the farmers are trying to sell whatever little is left,” said Mayank Sinha, convener, National Alliance Group for Denotified and Nomadic Tribes (NAG-DNT).

READ: Coronavirus crisis: Why not a salary challenge at the national level?

Looming food insecurity

The Sabars are now selling fish they catch from local ponds to meet expenses and buy basics such as rice and flour.

“We have received 2 kg rice and 500 gm pulse on our ration card but it is difficult for a family to sustain on this,” said Ratnabali, 23, from Latpada village, whose mother works as domestic help.

“In some families, they have got less than this. If this situation continues, what will the Sabars do? Others don’t understand this situation we are in,” she added.

Food security will increasingly become a problem with time, as most villagers are still surviving with the previous month’s ration. The West Bengal government claims to have reached 78.8 million beneficiaries through the Public Distribution System (PDS), the survey noted. While all 33 families had a PDS card, only two got the extra ration of 5 kg rice.

Twenty four of these families are also entitled to free grains from the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme with the presence of either a pregnant woman or children below six years, but only 17 families have received free grains.

Children who were receiving food through the anganwadi centres are also facing a crisis. “We are looking at an increase in malnutrition among children,” said Rakhshit from PBKSKS, “there is also possibility of an increase in child deaths.”

The survey found that even though no villager has gone hungry yet, most have managed because of loans or advances.

After the survey was conducted, “rice distribution under the PDS extended to more number of blocks in the area but the tribespeople reported that the quantity is still insufficient an there are many who still haven’t received any ration,” said Sinha from NAG-DNT.

Government relief schemes

Government schemes that these tribes could have fallen back on in the absence of regular wages are either not enough for sustenance or are not reaching all. “While many schemes have been announced, the access and reach of these schemes still remains limited,” found the report, which collated responses as on April 6, 2020. “Even after April 6 there hasn’t been much difference in the status of cash transfers received by the community, said Sinha.

“Denotified tribes across the country are engaged in the informal economy, and the lockdown has hit them severely,” said Sinha. “A majority of these tribespeople either do not have ration cards or do not live in the states where these cards were made because they keep migrating–either way, it means that these people would not be able to access the government’s relief packages.”

As part of its relief efforts, the Centre had announced on March 26, 2020, that under the Ujjwala Scheme, free gas cylinders would be provided to 80 million poor families for the next three months. While most villagers were unaware of this scheme, of the 11 who were a part of it, none had received free cylinders. They said they did not have money to pay for cylinders, if required to.

About 87 million farmers who are beneficiaries of the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi and are entitled to a sum of Rs 6,000 annually, would be given Rs 2,000 as a “front-loaded matter,” Nirmala Sitharaman had announced. Of the 33 people surveyed, only one had received a partial amount of Rs 1,000 till March 2020, even as several farmers have incurred massive losses as their crops have rotted.

“Since the lockdown, we Sabars are facing a lot of problems,” said Jalandhar, 59, from Manbajar block. “We haven’t been able to buy even salt and oil. Those who grow vegetables are not finding ways of selling it. The cucumber yield has completely rotten and the watermelons are going to face the same now.”

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman had said in March 2020 that over 200 million women Jan Dhan Account holders would be given Rs 500 per month. Subsequently, the government said the money was disbursed to 200.5 million women as on April 22, 2020. Of the 33 villagers surveyed, only five had Jan Dhan accounts. Of these, one had received the money while the other four women had not received anything yet.

The Centre had announced in March 2020 that pensions given to 29.8 million widows, senior citizens and differently-abled under the National Social Assistance Program will be given an advance pension for three months and an ex-gratia amount of Rs 1,000. However, the survey found that of the 13 families eligible under the scheme, only 11 have received the pension for this month and none are sure of having received any advance, while no family has received any ex-gratia amount.

Meanwhile, the “Prochesta” scheme launched by the West Bengal chief minister has not reached any of the 33 people. Under the scheme, daily wage labourers were to be given an assistance of Rs 1,000 per month during the lockdown.

About 32 families who have a job card under MGNREGS, none have received any payment or any job over the last few months. The Centre had announced that every worker will get an additional wage of Rs 2,000 annually and funds will be released to clear pending wages. However, “none of the villagers seem to have benefitted from this announcement thus far”, the survey said.

(Published in an arrangement with IndiaSpend.)