India is once again facing tariff uncertainty from its most important trading partner. The United States has threatened punitive duties of up to 500% on Indian exports if New Delhi continues to purchase Russian oil. Coming at a time when 2026 was expected to stabilise India’s trade outlook, this marks a sharp escalation in the use of trade policy as a geopolitical weapon. For India, the dilemma is stark. Buying costlier crude strains public finances and stokes inflation, but complying with coercive demands from Washington risks eroding strategic autonomy. With nearly 85% of its crude oil requirement met through imports, India has little room for miscalculation.

The trigger is Washington’s growing push to enforce compliance with its sanctions regime against Moscow. US President Donald Trump has publicly backed the bipartisan Sanctioning Russia Act of 2025, signalling that energy-importing countries will be forced to choose between access to the American market and continued engagement with Russia. For India, which has sought to navigate the Ukraine conflict through calibrated neutrality rather than alignment, this is no longer a purely diplomatic challenge. It is now a question of economic resilience and long-term energy security.

READ I Why India-Russia relations will withstand western pressure

Why Russian oil matters to India

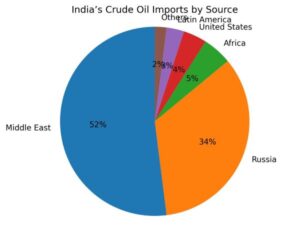

Since the Ukraine war began in 2022, Russia has emerged as India’s largest crude supplier. The reason is simple: price. Deep discounts on Russian oil helped India blunt the inflationary shock that followed the war and Western sanctions on Moscow. Lower crude prices feed directly into transport costs, fertiliser subsidies, and food inflation. For a fast-growing economy with rising energy demand, affordability is not a negotiable variable.

Asking India to walk away from these supplies is therefore not a marginal adjustment. It implies higher import bills, renewed pressure on the current account, and difficult fiscal trade-offs. From New Delhi’s perspective, the US demand is economically costly and politically sensitive.

READ I India-Russia ties need an MSME-led economic strategy

A tariff threat that changes the equation

What sets the current episode apart is the scale of Washington’s threat. A 500% tariff would effectively shut Indian goods and services out of the US market. The United States is India’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade in goods and services crossing $132.2 billion in FY25. India’s trade surplus stood at $40.8 billion, reflecting the strength of software services, pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, and textiles.

A tariff shock of this magnitude would undo years of painstaking market access gains. It is also meant to send a broader signal. US Senator Lindsey Graham has said the proposed legislation is designed to give the White House “maximum leverage” over countries such as India to choke off financing for Russia’s war effort. India is not a collateral casualty; it is a test case.

What is often missed in this debate is that the real pressure points lie beyond tariffs. India’s Russian oil trade depends on shipping insurance, reinsurance, port services, and trade finance systems still dominated by Western firms. Secondary sanctions targeting these channels could disrupt supplies even without formal trade bans.

The immediate exposure would fall not on the state but on refiners such as IOC, BPCL, HPCL, and private players with export-oriented margins and dollar financing. Any disruption would quickly feed into domestic fuel pricing, transport costs, and food inflation, areas with high political sensitivity. This constrains New Delhi’s room for manoeuvre more tightly than abstract notions of strategic autonomy suggest. The choice is therefore shaped as much by balance sheets and ballots as by diplomacy.

READ I India-Russia trade ambitions face geopolitics and hard economics

Why India cannot absorb oil shocks

India’s options are narrower than they appear. Unlike China, it cannot offset a US market closure by pivoting inward or rerouting exports at scale. Unlike Europe, it lacks the fiscal space to indefinitely subsidise energy costs if forced to switch to more expensive suppliers. And unlike smaller economies, it cannot avoid scrutiny. India’s size, visibility, and growing geopolitical role ensure that it sits squarely in Washington’s line of sight.

This combination leaves New Delhi in a strategic bind. Compliance carries long-term costs. Resistance carries immediate ones.

Short-term accommodation, unresolved tension

In recent months, India has signalled limited accommodation. Russian oil imports fell sharply in December 2025, touching a three-year low. The message was carefully calibrated: responsiveness without capitulation. This may buy time, but it does not resolve the underlying tension between US geopolitical priorities and India’s energy calculus.

A deeper concern is credibility. Even if India adjusts today, what prevents similar demands tomorrow? If energy trade can be penalised this severely, other policy domains such as data localisation, digital taxation, defence procurement, or industrial subsidies could follow. Strategic autonomy loses meaning if it is negotiated issue by issue under threat.

Energy security and Russian oil

Energy security is not merely about access; it is about diversity, affordability, and resilience. Over-dependence on any single supplier creates structural vulnerabilities. Ironically, US pressure to cut Russian imports could push India back toward a narrower West Asian supplier base, reviving risks New Delhi has spent decades trying to manage.

The longer-term response lies neither in defiance nor in capitulation. India must reduce its exposure to external shocks. That means accelerating domestic exploration, expanding strategic petroleum reserves beyond current capacity, and compressing timelines for the energy transition. Renewable energy, electric mobility, and green hydrogen are not climate indulgences; they are strategic assets. Every additional megawatt of solar or wind power reduces vulnerability to geopolitical coercion.

Diplomacy also needs diversification. India should work with other large energy importers such as Japan to push back against the extraterritorial use of trade sanctions. Multilateral forums may be weakened, but coordinated signalling still matters. Washington, too, has an interest in avoiding a precedent that undermines partnerships rather than strengthening them.

This episode is larger than oil or tariffs. It is a test of whether strategic partnerships can accommodate national interest, or whether economic coercion will become the default tool of statecraft. India’s response will shape not just its energy security, but the terms on which it engages a more transactional global order.