Venezuela crisis: 2026 was expected to bring some stability to global trade after successive shocks. Instead, the sudden US military intervention in Venezuela and the capture of President Nicolás Maduro has opened a fresh fault line. Coming on top of wars in Ukraine and Gaza, shipping disruptions in the Red Sea, and sanctions-linked instability in Myanmar, the episode underlines a basic shift: geopolitics is now the dominant driver of trade outcomes.

For India, the direct economic exposure is small. The strategic signals, however, are not. Energy markets, sanctions, and great-power rivalry are increasingly intertwined, and distant political shocks now travel quickly through prices, capital flows, and supply chains.

READ | US intervention in Venezuela and the Monroe Doctrine

Oil markets react first, but supply risks are modest

Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, however its actual output has been constrained for years by underinvestment, sanctions, and institutional decay. Any military escalation involving a major hydrocarbon producer tends to unsettle markets, even when immediate supply disruptions are limited. Traders may know that Venezuela’s lost barrels are largely priced in, but geopolitical risk premiums rise sharply during moments of uncertainty.

For oil-importing economies, the consequences are familiar. Higher crude prices feed into inflation, widen current account deficits, and complicate monetary policy. India imports over 85% of its crude oil. A sustained rise in prices would strain both household budgets and fiscal arithmetic, just as central banks are attempting to normalise policy after years of disruption.

Limited exposure does not mean limited vulnerability

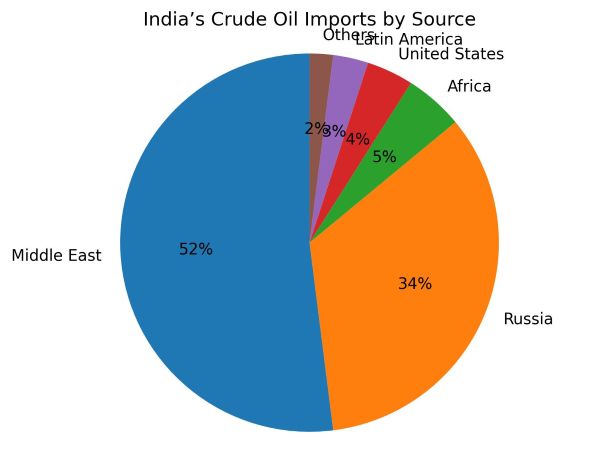

India’s direct trade exposure to Venezuela is marginal. Bilateral trade has remained below $2 billion in recent years. Imports of Venezuelan crude, once significant for Indian refiners designed to process heavy oil, fell sharply after US sanctions tightened in 2019. Indian refiners responded by diversifying supplies towards Russia, West Asia, and the United States.

This diversification has reduced immediate supply risks. It has not eliminated vulnerability. Oil is globally priced. Even when India does not import Venezuelan crude, it pays the international price set by marginal supply and sentiment. Energy shocks therefore reach India through prices rather than volumes.

Frozen upstream investments and a narrowing strategic space

Venezuela once occupied a central place in India’s overseas energy strategy. In the 2000s and early 2010s, Indian public sector firms invested heavily in the Orinoco heavy oil belt. ONGC Videsh holds stakes in the San Cristóbal and Carabobo-1 projects, developed with PDVSA. These investments have been effectively frozen for years, with production crippled by lack of technology and capital and revenues trapped by sanctions.

A US-led restructuring of Venezuela’s oil sector could produce mixed outcomes for India. Easing sanctions and injecting capital could revive output and stabilise global supply, benefiting oil-importing countries. It may also allow Indian firms to recover long-pending dues running into hundreds of millions of dollars.

At the same time, greater US control over Venezuelan energy assets would narrow the strategic space for other players. Energy security is not only about price and volume. It is also about predictability and autonomy. When access to resources becomes conditional on political alignment, commercial logic recedes. For a country that has sought to balance relations across rival blocs, this shift raises uncomfortable questions.

READ | Venezuela crisis turns into a public health emergency

Energy transition rhetoric meets fossil fuel power politics

The Venezuela episode also exposes a deeper contradiction in global energy politics. Even as advanced economies commit to decarbonisation, fossil fuels remain central to geopolitical power. Control over oil and gas resources continues to shape foreign policy choices. The scramble over Venezuela’s reserves sits uneasily with climate rhetoric.

For developing economies, this creates a dual challenge. The transition to renewables is a climate necessity, but fossil fuels still anchor energy security and macroeconomic stability. The episode underlines that the transition will be uneven, contested, and shaped as much by power politics as by climate commitments.

China’s shadow over Venezuelan crude

China’s role adds another layer of complexity. Over the past decade, Beijing has emerged as the largest buyer of Venezuelan crude, accounting for more than half of its exports. Many of these flows operate under opaque arrangements that blur the line between trade, debt repayment, and strategic leverage.

Any US attempt to reassert control over Venezuelan production is therefore also a signal to China. Energy resources are no longer neutral commodities. They are strategic assets in a widening contest for influence. That shift matters for India, which has relied on diversification and commercial pragmatism rather than geopolitical alignment to secure energy supplies.

READ | US intervention in Venezuela threatens rules-based global order

When intervention erodes the rules that trade depends on

Beyond oil and sanctions, the Venezuela episode carries a quieter but more consequential signal. A unilateral military intervention to remove a sitting head of state, without clear multilateral authorisation, weakens the already fraying norms around sovereignty and non-intervention. Global trade relies not only on open markets but on predictable rules governing borders, governments, and the use of force. When those rules are bent selectively, commercial risk rises even for countries far removed from the conflict.

For middle powers like India, this erosion matters. India has consistently argued for restraint, dialogue, and respect for territorial sovereignty—whether in Ukraine, Gaza, or Myanmar. A world in which regime change is normalised through force creates uncertainty that no amount of trade diversification can fully hedge against. Contracts, investments, and supply chains are only as secure as the political order that underpins them.

The precedent is especially troubling for resource-rich but institutionally fragile states. History suggests that such countries are not stabilised by intervention; they are often destabilised further. The collapse of governance then spills outward—through volatile commodity prices, disrupted shipping routes, and abrupt shifts in sanctions regimes. Trade becomes collateral damage in geopolitical contests rather than a stabilising force between nations.

What India should take away

The immediate macroeconomic impact on India may be limited. Inflationary pressures would rise if oil prices spike, but fiscal buffers and fuel tax flexibility provide some room to absorb shocks. The larger risks lie elsewhere—in sanctions regimes that can change overnight, in overseas investments exposed to political intervention, and in a global energy system increasingly shaped by power rivalry.

India’s response must therefore be deliberate. Supplier diversification remains essential, as does faster diversification of energy sources. Expanding domestic production where feasible, investing in strategic petroleum reserves, and accelerating renewable deployment are no longer just climate choices. They are geopolitical hedges. Overseas investments by Indian firms also require stronger sovereign backing and clearer risk-sharing frameworks, especially in volatile regions.

Venezuela is not an isolated episode. Resource-rich countries with weak institutions are often more vulnerable, not less. When they fracture, the spillovers travel far—through oil markets, financial systems, and diplomatic alignments. For India, the immediate impact may be small. The signals, however, are large. Energy security can no longer be separated from geopolitics, and complacency would be costly.