A spate of recent incidents—from protests outside Hindu temples in Texas to rising hostility toward Indian professionals in Silicon Valley—has unsettled Indian Americans. The anxiety feels sharper than before. It coincides with tighter visa scrutiny, louder anti-immigrant rhetoric, and the return of culture-war politics to the centre of American public life. For many, the question is whether something fundamental has shifted in the United States. History, data, and policy incentives suggest otherwise.

What looks like a structural change is closer to a familiar moment in American politics- when economic stress and political mobilisation find an easy target. These moments are loud and unsettling. They are also temporary, because markets, institutions, and demography have a way of pushing back.

READ I America’s H-1B visa reform rewards scale, not talent

A familiar American pattern of suspicion

The US has repeatedly gone through phases of suspicion directed at specific communities. In the 1950s, it was communists. Later decades saw African Americans, Hispanic migrants, Muslims, and East Asians framed as threats to jobs, security, or national identity. Each phase was accompanied by moral panic, legislative overreach, and social stigma. Each eventually faded.

The pattern is well documented, including in long-running studies by institutions such as the Brookings Institution and the Pew Research Center. Periods of economic uncertainty tend to produce scapegoats. When labour markets tighten or inequality becomes politically salient, cultural explanations substitute for economic ones. Indian Americans now find themselves in this position not because they are marginal, but because they are visible.

Visibility, in American politics, often precedes resistance.

READ I H-1B visa shock: What it means for India’s jobs strategy

Indian Americans: Demography and economics

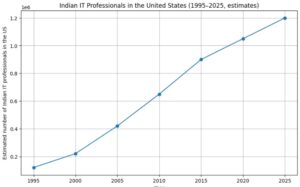

Indian Americans today form one of the most economically integrated migrant communities in the United States. According to Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data, the Indian American population reached about 5.2 million in 2023, growing by nearly 174% since 2000. About 77% of Indian adults aged 25 and above hold at least a bachelor’s degree, far higher than the national average. Median household income for Indian-headed households stood at roughly $151,200, compared with about $75,000 for U.S. households overall.

These figures matter because American immigration policy, in practice, bends toward economic self-interest. High-skill migrants fill gaps that domestic education systems have struggled to close, particularly in technology, healthcare, and advanced research. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics continues to project shortages in several STEM and medical occupations through the next decade.

Rhetoric may turn hostile. Policy rarely sustains positions that weaken competitiveness for long.

READ I India looks to reverse brain drain amid US uncertainty

The H-1B flashpoint is policy, not permanence

The H-1B visa programme has become the focal point of current hostility. Proposals ranging from steep fee increases to wage-weighted selection systems are framed as protecting American workers. In practice, they function more as political signals than as lasting changes.

Data from the U.S. Department of Labor show that H-1B holders are concentrated in specialised, high-skill roles. Research by the National Foundation for American Policy finds no credible evidence that the programme depresses overall wages. When visas tighten, firms do not suddenly discover large pools of local talent. They shift work offshore, automate tasks, or relocate research and development.

This is why administrations that campaign against skilled migration often soften their stance in office. Universities, technology firms, healthcare systems, and state governments exert counter-pressure. The costs of restriction show up quickly—in productivity, investment decisions, and tax revenues.

Political noise versus institutional gravity

What feels different today is less the prejudice itself than the speed and reach with which it now travels. Social media amplifies fringe narratives and collapses the distance between rhetoric and threat. Online hostility creates the impression of permanence even when policy remains fluid.

Institutional gravity still matters. Indian Americans are increasingly citizens, voters, donors, and office-holders. Their demographic profile is young. The median age of U.S.-born Indians is just over 13 years, and a majority are under 18. This is not a transient workforce. It is a settled community with long-term civic stakes.

Backlash has also intensified as Indian Americans have become more politically assertive. In American history, resistance often follows participation. Over time, participation reshapes the terms of debate.

Economic reality will reassert itself

The current phase also reflects labour-market anxiety rather than economic collapse. In late 2025, U.S. GDP growth remained strong even as unemployment edged higher and hiring slowed. That combination—strong output alongside job insecurity—has historically fed nativist rhetoric.

As cycles turn, the narrative changes. Groups portrayed as “job takers” during periods of uncertainty are later reframed as contributors when growth accelerates. This pattern was visible in earlier debates over East Asian engineers in the 1980s and Eastern European scientists after the Cold War.

Indian professionals are not insulated from political cycles. But their skills remain aligned with the structural needs of the American economy. That alignment tends to outlast electoral moods.

The unease felt by Indian Americans is real. It carries social and psychological costs. It does not, however, point to a durable shift in American policy or identity. The United States remains dependent on skilled migration, demographically committed to diversity, and institutionally resistant to permanent exclusion.

The risk lies in mistaking a noisy phase for a settled future—especially when policy can still swing sharply at the margins, at the state level or through administrative discretion. For policymakers, restraint matters more than rhetoric. For India, sustained institutional engagement with the United States matters more than reacting to political cycles. And for Indian Americans, history offers perspective: America argues loudly with itself, but it rarely stays where its fears momentarily take it.