Urban homelessness in India: On a winter night in Delhi, families clutching tattered blankets huddle beneath flyovers. Children and older persons sleep on pavements, beside trampling traffic and honouring the cold gusts that sweep the capital. Some seek refuge at the entry of a hospital, others in the nooks of railway stations. The image is stark, yet it lies in sharp contrast with the narrative of India’s rapid urban growth and economic ambition. For all the glowing metrics of urbanisation and rising skyscrapers, the deep reality of homelessness remains hidden from the development story.

The constitutional promise of life with dignity under Article 21 is confronted every night by thousands lacking even a roof. According to the 2011 Census, India counted 1,772,889 homeless people, of whom 938,348 were in urban areas. This is the last full national enumeration. It is now widely accepted that these figures are substantial under-estimates.

READ I Road safety crisis: Why accident deaths keep rising

Urban homelessness and the invisible India

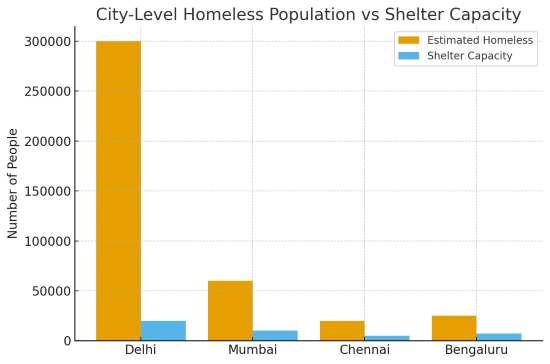

For example, in Delhi, a 2024 civil-society head-count by Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath found 154,369 people sleeping on the streets over five nights; extrapolation suggested a total homeless population of over 300,000 in the city alone. Meanwhile, a written reply to the Lok Sabha in March 2023 reported reliance on Census 2011 data, and stated that no newer national survey was undertaken.

Why the discrepancy? Because homelessness is mobile, hidden and entwined with informal work. Counting only people in shelters or on pavements on one night will omit those who use night jobs, migrate seasonally, or sleep temporarily in makeshift dwellings. Many escape official enumeration. Civil-society studies emphasise that women, children, elderly and mentally-ill persons are systematically excluded from tabulations of homelessness.

One of the paradoxes is this: India is the world’s fifth-largest economy, urbanisation is proceeding apace, yet the basic condition of shelter eludes large numbers of its citizens. Urban homeless remain outside of, rather than included in, the story of growth.

Schemes on paper, gaps on the ground

The Union government administers the Shelters for Urban Homeless (SUH) scheme under the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana – National Urban Livelihoods Mission (DAY‑NULM) and supports the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana – Urban (PMAY‑U) housing scheme. According to a July 2024 press release from the ministry of housing and urban affairs (MoHUA), some 1,986 shelter homes have been created under SUH with capacity for more than 141,000 persons.

On the housing front, PMAY-U has sanctioned over 1.18 crore houses; of those, more than 114.33 lakh have been grounded for construction and over 85.04 lakh completed/delivered.

But the gap between policy and ground reality is large. Capacity for 1.41 lakh under SUH is dwarfed by evidence that a single city like Delhi has 3 lakh homeless persons. Shelters may exist on paper, but access is often restricted by requirements such as photo-ID, local address, or migrant status, which effectively exclude many. NGOs in Delhi report that even when shelters exist, they remain under-occupancy during day hours and inadequate at night.

Moreover, PMAY-U is a housing scheme for eligible urban households, but does not target the chronically homeless per se. Many homeless persons are migrant day-labourers, people in informal work, with no permanent urban address. They are left out of the beneficiary lists. Even in cases where shelter is provided, the transformation from shelter to housing—especially affordable or rental housing—is missing. The result is that homelessness persists, hidden yet systemic.

Law, courts and the right to shelter

Over the years, the judiciary has recognised that the right to shelter is integral to the right to life under Article 21. The long-pending PIL in W.P.(C) 55/2003 and related matters has led to orders asking states to furnish data on shelter homes, to upgrade facilities and to monitor capacities. In August 2025 the Supreme Court of India directed the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) to inspect and report on the closure of shelters in Delhi (Anand Vihar and Sarai Kale Khan) due to metro-construction, asking whether alternative sites can accommodate over 1,000 displaced persons, and that the inspection be done after 8 pm to reflect occupancy.

The question is: can judicial nudges substitute for a coherent national urban homelessness policy? The answer must be negative. The courts flag gaps, but constructing policy, financing it, aligning it with land markets and urban planning is a task for the executive and legislatures—not activism via courts alone.

Why urban homelessness persists

Urban homelessness in India is not simply a short-term emergency. It is linked to the dynamics of urbanisation, land markets, informal work, and weak social protection. Migrant labour flows into cities seeking work in construction, services and logistics. These jobs are informal, low-paid, and without security. Such workers often cannot afford urban rents of ₹3,000–₹5,000 or more in Delhi, so they sleep at construction sites, pavement curbsides, under flyovers. The SAM:BKS survey in Delhi found many homeless families live where jobs are concentrated though housing is absent.

Then there is the real-estate effect. City planning and world-class city ambitions often privilege land for offices and high-rise housing, while displacing informal settlements and night shelters. The redevelopment of transit hubs or metro corridors sometimes leads to demolition of shelters before adequate alternatives are in place. The directions in Delhi where land owned by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) was earmarked for redevelopment is one such instance.

The underlying structural failure is weak rental housing and social housing systems in cities. Without affordable rental stock, informal workers are pushed into street-sleeping. Without integrated livelihoods, health, mental-health and child-protection support, shelters become stop-gaps rather than pathways.

A realistic policy agenda

A national urban homelessness strategy must go beyond shelters and housing targets. First, the government should commission updated, credible national and city-level data on homelessness, using mobile enumeration, hot-spot mapping and seasonal head-counts. Without accurate numbers, targeting remains flawed. Second, it must expand and upgrade shelter capacity with defined norms for every city, ensuring 24×7 access, family units, women-and-child friendly spaces, and linkages to health and livelihood support.

Third, a national urban homelessness strategy should integrate housing, health, mental health, child protection and livelihoods; it must cover the entire continuum from street-sleeping to stable housing and employment. Fourth, transparency and accountability are needed in the implementation of PMAY-U and SUH. Audit logs, occupancy data, migrant-friendly criteria and linkages to employment must be introduced.

India cannot claim the label of Viksit Bharat while hundreds of thousands sleep exposed to cold, heat and insecurity. The real economic question is not just growth but who the growth leaves behind. A society that builds skyscrapers for the few yet ignores the roof-less for the many fails its most basic moral and constitutional test.