Access to universal healthcare: In a world that relentlessly pursues equality and inclusivity, gender disparities in healthcare utilisation persist as a pressing concern. This article delves into research work on gender inequalities in healthcare access, with a focus on Rajasthan. Here, BSBY, a government health insurance programme, seeks to ensure equitable access to healthcare services. The scheme closely mirrors the Union government’s Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) initiative, which extends its coverage to millions of individuals across the nation.

The research underscores the necessity of addressing gender disparities in healthcare. Regrettably, India ranks among the world’s poorest performers concerning women’s health. An index measuring factors such as women’s perceived access to care, the quality of care received, their health-related opinions, and safety reveals India’s troubling position, ranking 14th from the bottom. This disheartening placement aligns India with countries like Sierra Leone, highlighting the gravity of this pervasive issue.

It is an irrefutable fact that gender bias, pervasive in healthcare provisioning through the provision of fewer healthcare services and treatments to women, leads to dire health outcomes for them. This deeply entrenched issue, often referred to as ‘missing women,’ has reached an estimated magnitude of 63 million in India, with the majority comprising adults. These disparities have endured over time, prompting policymakers to launch various subsidies and health insurance schemes in their efforts to address them.

READ I Kerala Story: Migrant workers struggle for equitable healthcare access

India’s universal healthcare schemes

Government health insurance initiatives in India, notably PMJAY, have played a pivotal role in enhancing healthcare access for economically disadvantaged households. These commendable programmes offer cost-free or significantly subsidised care at both public and private healthcare institutions. A key innovation embedded within these initiatives is the inclusion of private hospitals as care providers for economically disadvantaged households, with these hospitals later filing claims for reimbursement from state insurance programmes.

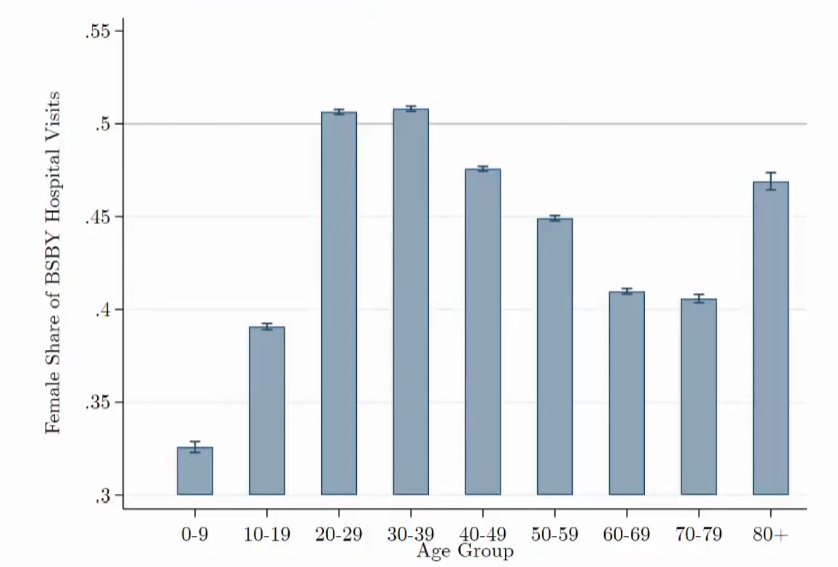

Gender gap in hospital visits

Gender gap among beneficiaries

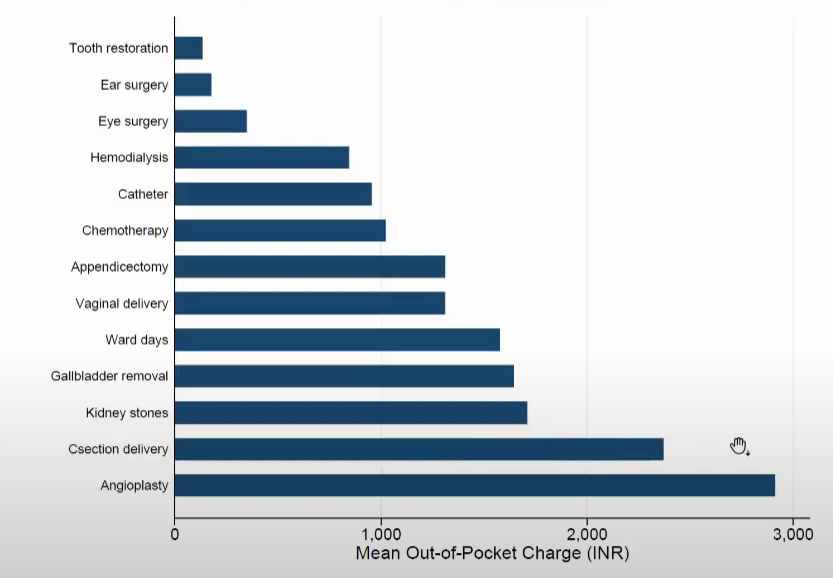

No free lunch: Out of pocket expenditure

The core question addressed in the researcher work revolves around the effectiveness of subsidising hospital care in mitigating gender inequality in healthcare utilisation. The study’s epicentre is the Rajasthan programme, encompassing 46 million individuals, and drawing upon claims data spanning from 2016 to 2020.

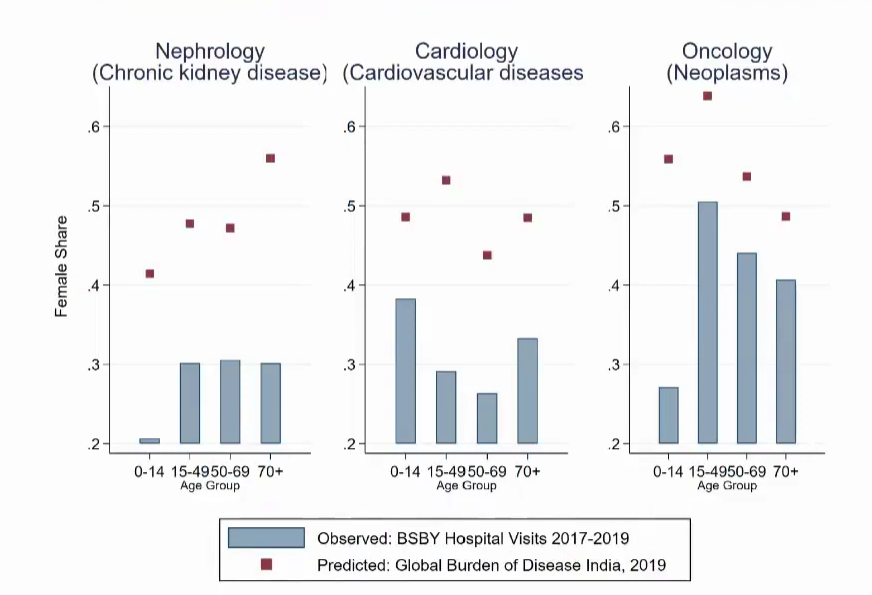

Key findings and gender disparities

The primary research findings shed light on significant gender disparities, encompassing both the likelihood of receiving care and the nature of care delivered. Despite the policy’s noble intention of delivering free care, hospitals frequently impose out-of-pocket expenses on patients, a phenomenon that disproportionately affects women. Additionally, the incurrence of transportation costs, in terms of both time and money, compounds the widening gender gap in healthcare utilisation.

The journey rightly underscores that merely reducing the cost of care may not be adequate to narrow these gender disparities. Universal subsidies, while instrumental in elevating overall healthcare utilisation, may not be sufficient to bridge the gender gap, as both men and women benefit. To truly achieve gender parity, we must augment these efforts with targeted interventions designed to address the specific barriers obstructing women’s access to healthcare.

Identifying gender-specific barriers

The research places significant emphasis on the identification of gender-specific costs and barriers that impede women’s access to healthcare. By shedding light on these obstacles, policymakers can craft more effective interventions to combat gender disparities. In summary, while universal subsidies enhance female healthcare utilisation, the implementation of gender-targeted interventions emerges as an indispensable imperative for achieving genuine equity.

Gender disparities in healthcare access persist across the globe, spanning various regions, including India. Government health insurance programs have indeed achieved commendable progress in bolstering healthcare access for economically disadvantaged populations. However, as this research compellingly illustrates, gender disparities persist even when care is subsidised or rendered free.

To achieve authentic equity, policymakers must expand their purview beyond the mere reduction of care costs. They must proactively implement specific interventions tailored to address the unique challenges women face in accessing healthcare. Only through a comprehensive understanding and diligent redressal of these gender-specific barriers can we hope to attain gender parity in healthcare utilisation, thus elevating the health and well-being of all our citizens.

Access to high-quality healthcare constitutes a fundamental right, one that should be equally accessible to every member of our society. However, as is evident in numerous regions worldwide, India included, gender disparities in healthcare access endure, even within universal healthcare programs designed to encompass the entire populace. In this op-ed, I have dissected a researcher’s work that delves into gender disparities in healthcare access, casting a particular spotlight on Rajasthan’s universal healthcare program. This illumination extends to encompass the factors contributing to these disparities and potential avenues for their resolution.

(This article is the edited excerpt of a presentation, Gender disparities in utilisation of government health insurance in India, by Pascaline Dupas, Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Princeton University.)