With every passing year, nature seems to test the limits of India’s preparedness more severely than before. The latest reminder has come in the form of Cyclone Montha, a storm building over the Bay of Bengal and heading toward the coasts of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. Nearly 50,000 people have already been evacuated from vulnerable zones, schools have shut, and disaster response teams are in place. It is a familiar ritual — one that shows both the country’s growing capacity to respond and its persistent vulnerability.

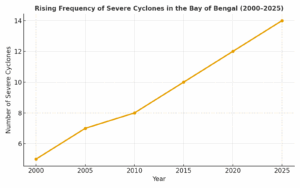

Each cyclone, flood, or heatwave now carries a message that is impossible to ignore. Climate change is no longer a distant or seasonal phenomenon. It is a relentless, year-round stress test of governance, infrastructure, and foresight. India may be better at saving lives than it was two decades ago, but the scale of exposure — in population, assets, and livelihoods — has multiplied. The question is no longer whether the systems will hold, but whether they will evolve fast enough to match the pace of the threat.

READ I Will India’s financial sector reforms win back investors?

Cyclone Montha: Lessons from the Bay of Bengal

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), Cyclone Montha has formed over the Bay of Bengal and could make landfall today. Authorities have shut schools and colleges, deployed disaster-management teams, and shifted thousands from low-lying zones to safer shelters. The RTGS War Room is monitoring rainfall, wind speed, and inundation in real time using satellite phones, digital radios, and V-SAT systems to ensure uninterrupted communication.

These proactive measures mark progress since the 1999 Odisha super-cyclone, which killed nearly 10,000 people. India’s institutional response is far stronger today. Yet, the resilience of physical infrastructure remains the weak link. Early-warning systems and evacuation plans can only work if roads, bridges and relief centres survive the storm. In many coastal belts, flood-prone shelters and inaccessible roads continue to threaten lives despite better preparedness.

Resilience demands investment

The evacuation of 50,000 people ahead of Cyclone Montha is commendable, but India’s high-risk coastal exposure persists. Investment in storm-surge defences, resilient housing, and elevated utilities has been inconsistent. Without long-term financing and planning, these protective systems remain patchy.

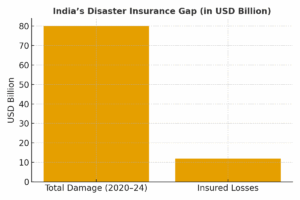

One promising step is the government’s exploration of a climate-linked parametric insurance model, which releases payouts automatically when pre-defined weather thresholds — such as wind speed or rainfall intensity — are reached. For a country ranked among the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations, this could be transformative. If implemented successfully, India would become one of the few major economies with such a system at scale.

Financing remains the weakest link in India’s climate-resilience strategy. Most state budgets still prioritise post-disaster relief over long-term adaptation. Building sea walls, upgrading drainage, and flood-proofing power lines require predictable, multi-year funding — something current fiscal frameworks do not ensure. India could consider a National Adaptation Finance Facility, backed by green bonds and blended finance, to help states invest in preventive infrastructure. Without such an institutional mechanism, every cyclone will renew the cycle of destruction and relief, eroding both resources and public confidence.

A deeper structural challenge lies in unplanned coastal development. Expanding ports, industries, and housing projects often violate coastal-regulation norms, shrinking natural buffers such as mangroves and wetlands. Urban sprawl across floodplains and reclaimed land, particularly in Chennai and Visakhapatnam, has worsened storm impacts. Enforcing Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) rules and integrating hazard mapping into urban master plans are essential. Unless development plans account for future sea-level rise and erosion, the next cyclone could undo years of economic progress.

From relief to prevention

Currently, most funding for disaster recovery flows through the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF) and State Disaster Response Funds (SDRF). These mechanisms support relief but not prevention. The Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) argues that India must shift from a “wait-and-react” mindset to a “design-and-resist” strategy — building infrastructure that anticipates extreme weather instead of merely responding to it.

That means state disaster protocols must evolve from evacuation-centric responses to resilience-oriented systems. As Cyclone Montha approaches, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha will face the real test: whether shelters can retain power, sanitation, and medical support, and whether district administrations can coordinate effectively even if communications fail.

Future of climate governance

To build genuine resilience, India must integrate community preparedness into everyday governance. Schools and public buildings should be retrofitted as storm-resistant shelters. Budgets must earmark funds for flood-resilient embankments, underground cabling, and real-time sea-level monitoring. The private sector too must invest in insurance and resilient infrastructure as part of its ESG commitments.

Real resilience begins at the local level. Panchayats, municipalities, and district administrations are often the first responders, yet their role in disaster management remains limited to implementing top-down directives.

Decentralised funding, capacity building, and community awareness can make them more effective. In Odisha’s past cyclones, trained community volunteers saved thousands of lives — a model worth replicating nationwide. Embedding climate literacy into local governance will ensure that preparedness is not an emergency drill, but a habit of daily administration.

Cyclone Montha is not an anomaly but a signal. Each storm now tests whether India is learning fast enough. The time for reactive relief is over — the time for climate resilience is now.