Despite the Indian economy clocking stellar GDP growth rates year after year, the government is faced with a sticky problem — weak investment by private sector for more than a decade despite several policy incentives. Every few months, the economy offers a familiar spectacle — a flutter of anxiety at the first sign of private sector slowdown. Commentators speak of waning confidence, investors grow uneasy, and policymakers brace for uncomfortable questions. But not every deceleration is a distress signal. Economies, like engines, occasionally downshift not because they are stalling, but because they are preparing for a more sustained run. India may be in such a moment — not of crisis, but of calibration.

Recent data do suggest a pause in private investment activity and a more cautious corporate mood. Growth in new project spending has softened, sanctioned project costs have declined, and the investment-to-GDP ratio has slipped to its lowest level in three years. These are not symptoms of collapse, but signs of restraint. The real challenge for policymakers is not to reignite the same pace at any cost, but to understand what this moderation reveals: an economy shifting gears toward a steadier, more deliberate trajectory.

READ I Why China’s critical minerals dominance will last years

What do macroeconomic indicators suggest

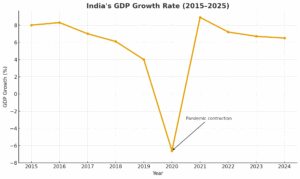

To understand the current phase of private sector slowdown, we must look beyond the headline numbers. India remains the fastest growing large economy, clocking 6.5 per cent GDP growth in 2024-25. The Reserve Bank of India’s foreign exchange reserves touched $697.9 billion in June, enough to cover 11 months of imports — hardly the picture of macroeconomic distress. What has slowed is not output itself but its composition and momentum.

Credit expansion, particularly to large corporates, has cooled noticeably. Retail loan growth, once galloping at 14 per cent, slipped to 11.9 per cent in July 2025. The number of new private sector projects sanctioned has declined, and credit to large industry grew at barely 1 per cent, even as micro and small enterprises (MSEs) saw an impressive 21 per cent jump. The divergence tells its own story: the slowdown is selective, not systemic.

In essence, India’s growth engine is not stalling but re-tuning. Demand is maturing, and firms are financing expansion through retained earnings and equity rather than heavy bank borrowing. The slowdown, therefore, may represent the beginning of a more balanced and sustainable growth phase rather than the prelude to contraction.

The anatomy of private sector slowdown

To call it a private sector slowdown without examining its anatomy would be misleading. Three distinct shifts stand out. First, India is moving from quantity to quality. Manufacturing and services activity both remain comfortably in expansion territory. The manufacturing PMI rose to 58.4 in October from 57.7 a month earlier, while services moderated from 60.9 to 58.8. The trend suggests that the easy gains of post-pandemic recovery are over, and growth is now anchored in efficiency, technology and value addition rather than volume.

Second, there is a visible decoupling between credit and investment. Large industrial borrowers, still cautious from past deleveraging cycles, have avoided new leverage. Meanwhile, MSEs are becoming the new engines of employment and production. Their rising credit share — 21 per cent growth year-on-year — indicates a deeper formalisation of the grassroots economy. This decentralisation of capital formation is healthy. It signals a broadening of India’s entrepreneurial base even as legacy conglomerates consolidate balance-sheet strength.

Third, the external environment has turned less hospitable. Softening global demand, the ripple effects of U.S. tariffs, and higher input costs have dampened exports and new corporate orders. Yet domestic fundamentals remain sound. Public investment continues at a brisk pace, inflation expectations are moderate, and the rupee has been relatively stable. The slower rhythm may, in fact, be affording Indian firms the breathing space to recalibrate supply chains, strengthen productivity and diversify markets.

What emerges is a portrait of an economy that is maturing rather than faltering. Having grown rapidly on the back of consumption and services, India is now quietly laying the foundation for investment-led, export-sensitive and innovation-driven growth.

Fiscal policy amid the transition

The challenge for policymakers is to read this transition correctly. There is a temptation — especially when growth rates dip — to reach for the old playbook of broad fiscal stimulus. That would be a mistake. The present moment does not call for pumping more liquidity or widening the deficit, but for precision investment and institutional reform.

The Union government has, in recent years, demonstrated fiscal restraint by keeping the deficit within glide-path limits and prioritising capital expenditure. That prudence must continue. The task now is to channel capital spending towards sectors that multiply productivity — logistics, renewable energy, digital infrastructure — rather than indiscriminately boosting consumption. India’s fiscal challenge is not a shortage of ideas but a shortage of executional bandwidth: too many schemes, too little follow-through.

Fiscal policy must also anticipate the compositional shift in growth. As large corporates hold back, small and medium enterprises need targeted support through easier credit access, supply chain integration, and technology adoption. Tax incentives, if any, should reward innovation and employment creation, not mere capacity addition. The government’s role, in short, is to steer the economy’s new gear with discipline, not to slam the accelerator.

Coordination with the Reserve Bank is equally essential. The RBI has maintained a cautious but accommodative stance, ensuring liquidity without fuelling inflation. As credit demand becomes more selective, monetary policy should focus on ensuring that genuine productive sectors — MSMEs, infrastructure, and export clusters — do not face funding bottlenecks.

Rethinking reserve management

The external front presents a contrasting picture of strength. India’s foreign-exchange reserves crossed $702 billion in October 2025, an increase of $4.5 billion in just a week. The RBI’s gold holdings, now valued above $100 billion, mark a significant strategic diversification away from the traditional US Treasury-heavy portfolio.

These developments underline a quiet transformation in India’s reserve-management philosophy. The focus is shifting from quantity to quality, from accumulation to composition. As private capital flows become more volatile and the global monetary order fragments, resilience must be built into the very architecture of reserves. Holding a diversified basket of currencies, gold and SDRs is no longer optional; it is a strategic necessity.

Furthermore, reserve deployment must coordinate with fiscal and defence policy. In a volatile world of supply-chain disruptions, energy insecurity and cyber-risk, reserves are not just buffers against currency volatility — they are instruments of national resilience. The RBI must, therefore, resist the urge to defend the rupee mechanically and instead use reserves judiciously to smooth volatility and strengthen external confidence.

The current phase of private sector slowdown should be seen not as an alarm bell but as a signal — a signal that the Indian economy is maturing and recalibrating. Having exhausted the post-pandemic momentum of consumption and credit, it is moving towards a steadier, investment-led model. The risks, of course, remain: global turbulence, corporate deleveraging, and persistent stress in real estate could yet cloud the picture. But these are challenges of adjustment, not of survival.

If fiscal and monetary authorities interpret the data correctly, India could emerge stronger from this transition. The lesson is simple but profound: economic growth is not an endless sprint; it must occasionally slow to build endurance. In macroeconomic terms, that means tightening fiscal focus, strengthening reserves, and allowing private enterprise to find its new rhythm.

India must treat the private sector slowdown as an inflection point rather than an emergency. The government should resist populist spending and instead deepen capital investment in infrastructure, green energy, and innovation. Fiscal prudence and strategic reserve management will offer more lasting stability than any quick stimulus.

The time has come to view slower private sector growth not as a failure but as evidence of economic maturity — the moment when an economy learns to run, not just sprint.