US-China rivalry in Asia: Fifty years after the Berlin Wall froze Europe, a perceptible frost is settling over the Malacca Strait. One needed only a quarter hour of US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth’s oratory at the Shangri-La Dialogue to feel the temperature plunge. His warning of an imminent Chinese threat drew the predictable rebuke from Beijing—yet what truly rattled the region was the echo of an age many believed entombed with the Soviet archives. A second Cold War is not a historian’s conjecture; it is a live rehearsal on prime-time television, playing out in the waters and markets of Asia.

Washington insists it wants peace. Unfortunately, peace now comes packaged with a shopping list: hike defence outlays to 5% of GDP, buy American hardware, patrol contested seas. In the same breath, the White House slaps punitive tariffs—145% in some cases—not only on Chinese goods but on items that criss-cross Vietnamese and Malaysian supply chains. Beijing retaliates by squeezing exports of gallium and graphite, reminding everyone that semiconductors require more than silicon. Thus, Asia receives both barrels: tanks for its treasuries and tariffs for its factories.

The paradox is exquisite. Trade between the two superpowers touches near-record volumes, yet every container now arrives with the whiff of a potential embargo. What began as a duel over intellectual property has mutated into a contest over who defines the Twenty-First-Century order—guns, chips or rules.

READ I India’s AI dilemma: Jobs vs productivity growth

The latent military peril

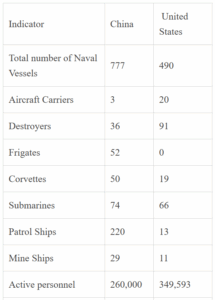

Strip away the rhetoric and the scoreboard is unsettling. China’s navy already sails with more hulls than the US fleet. Its shipyards, working three shifts, can replace tonnage faster than Washington can convene a Senate committee. Add a stockpile of over six hundred nuclear warheads, and the People’s Liberation Army appears intent on deterrence by saturation.

Chinese Navy vs US Navy – A comparison

America’s reply is a doctrine of denial, which translates into forward-deployed submarines, hypersonic tests and a web of intelligence sharing across the Indo-Pacific. In simpler English, each side is preparing for a night when diplomacy fails. A mis-calculated manoeuvre off the Philippine coast or a radar blip above Arunachal Pradesh could ignite an escalatory chain that neither hotline nor hashtag may arrest.

US-China rivalry in Asia

East Asia does not wish to choose sides, but geography and supply-chain mathematics leave little room for boycotts. ASEAN’s 10 economies trade more with China than with Europe and the United States combined. Yet none relish the idea of a Pax Sinica imposed by dredgers and coast-guard cutters in the Spratlys. This is why the same governments that queue for Chinese investment in ports also clamour for US freedom-of-navigation patrols—an exquisite diplomatic two-step worthy of Fred Astaire.

European leaders, too, smell the brimstone. President Emmanuel Macron, no stranger to grand speech, warned that forcing countries into binary camps risks demolishing the very institutions—WTO, WHO, the Paris Agreement—that underwrote post-war stability. His plea for coalitions of action rings truer in Jakarta than in Brussels: South-East Asian states know that when superpowers quarrel, the silk roads fray first.

India’s three-front dilemma

New Delhi sits at the intersection of three fault-lines. First, the contested land frontier with China, patrolled by troops lodged at altitudes inhospitable even to yaks. Second, a dependency on Chinese imports—pharmaceutical precursors, solar modules, electronics—etched into our balance of trade. Third, an American courtship that offers advanced technology, intelligence sharing and, whisper it, a moral veto in future crises.

How does one deter a neighbour, court a distant partner and still buy critical goods from the former? Strategic autonomy once enjoyed the luxury of ambiguity; today it demands precision. Our navy, though modernising, is half the size of the PLAN surface fleet. Cyber defences lag behind the digital-infrastructure boom. And while we congratulate ourselves on semiconductor ambitions, financiers price Indian fabs 150 basis points higher than peers because they cannot model the geopolitical discount.

The stealthy economic tax

A cold war collects its revenue long before the firing starts. Marine-war-risk premia in the South China Sea have risen by double digits. Global logistics firms quietly redirect traffic via Indonesia and Mexico, bypassing Shanghai and—alas—Chennai. Investors price uncertainty into everything from smartphone assembly lines to climate-finance bonds. Chatham House estimates that a one-percentage-point slowdown in Chinese GDP knocks 0.2 percentage points off Indian growth; the arithmetic is unforgiving.

Meanwhile, populist moods in Washington resurrect the spectre of secondary sanctions—penalties on anyone, including Indian entities, that transact with the wrong Chinese companies. The message is clear: economic ambiguity is expensive.

A doctrinal to-do list

First, harden the economy. Fast-track the overdue review of the ASEAN free-trade agreement; slash administrative tariffs that cripple intermediate imports; woo investors with genuine market access in return for resilient supply chains. If Vietnam can anchor four Apple suppliers in five years, so can Tamil Nadu.

Second, invest where deterrence is cheapest. Satellites, under-sea sensors, cyber firewalls and intelligence fusion cost a fraction of aircraft carriers yet multiply strategic options. Each rupee spent on better eyes postpones rupees spent on bullets.

Third, build coalitions that transcend the binary. Europe needs markets, India needs technology, and both need rules. The proposed India-EU Trade and Technology Council must move from press release to purchase order within the calendar year. Likewise, the Quad should expand its agenda beyond submarines to digital standards and pandemic preparedness—areas where middle powers can lead without provoking Chinese red lines.

Fourth, speak for the voiceless majority. Many in the Global South see India as a country big enough to say no to hegemony yet familiar enough with poverty to understand their anxieties. A foreign policy anchored in the constitutional promise of economic justice—and articulated without triumphalism—can still set the regional tone.

Reclaiming the Asian century

History’s tragedy is its repetition. The first Cold War sequestered resources, polarised alliances and delayed the economic ascent of entire continents. We owe the next generation a reprieve from that fate. The United States and China may feel compelled to test their strength; the rest of us are condemned to live with the fallout.

India’s task is not to play balancer in someone else’s see-saw; it is to enlarge the playground. By deepening economic partnerships, fortifying its own deterrence, and voicing a principled multilateralism, New Delhi can help steer Asia clear of another ideological ice age.

The point bears repeating: cold fronts are weather patterns, not destiny. With clarity, capacity and coalitions, India—and Asia—can still reclaim the warmth of an Asian century.