As the world emerges from the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, global entities are at work crafting a treaty to mitigate future crises through mutual cooperation and knowledge sharing. The World Health Organisation is spearheading negotiations for this first global pandemic treaty. Among the expected amendments are significant changes to the International Health Regulations 2005, aimed at enhancing cross-border information sharing in the event of potential infectious disease outbreaks. The treaty’s primary goal is to ensure equitable access to crucial resources such as vaccines and treatments while strengthening global defences.

The pandemic served as a wake-up call, exposing the vulnerability of nations when isolated during a global health crisis. The virus transcended borders, devastating economies and claiming millions of lives as even the most advanced economies struggled to respond. The subsequent unequal distribution of vaccines highlighted the disparities between affluent and less wealthy nations, necessitating the creation of the global pandemic treaty.

READ | US-China tech rivalry: Can America maintain its lead in AI

What is the global pandemic treaty

In March 2021, at the height of COVID-19, 25 heads of government and international agencies advocated such a treaty, marking a watershed moment in global health governance. The draft treaty encompasses a range of issues including pathogen surveillance, healthcare workforce capacity, supply chain logistics, technology transfers to facilitate vaccine production, and intellectual property (IP) rights waivers. It obliges nations to enhance their health systems and sanitation and advance toward universal health coverage. Separate discussions at the WHO aim to revise the International Health Regulations, requiring countries to promptly report health emergencies.

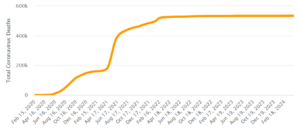

India: Total COVID-19 deaths

The treaty also tackles the vital issue of pathogen access and benefit sharing (PABS). Sharing virus samples and research data is crucial for developing vaccines. The treaty intends to create a framework for pathogen sharing that ensures equitable benefits for all involved. In exchange for data access, diagnostic, therapeutic, and vaccine manufacturers would be mandated to provide 10% of their products free of charge and another 10% at nonprofit prices. However, many developed nations and pharmaceutical companies have expressed dissatisfaction with the current draft’s provisions on access and benefit sharing.

The draft agreement also proposes establishing a robust regulatory body, creating a Conference of Parties (COP) to monitor treaty implementation—a formal arrangement under Article 19 of the WHO Constitution, as opposed to the more flexible opt-out options under Article 21.

The final session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) for the 30-page Pandemic Agreement took place in March. The final draft is set to be presented for approval at the World Health Assembly in late May.

While ideally, the proposal should be accepted unanimously, there is a risk of collapse due to concerns over national sovereignty and intellectual property rights. Opposition is notably strong among right-wing politicians in several countries, including the US who are wary of taxpayer money being used internationally. At the negotiation table, developing nations largely supported the revised draft, while developed nations uniformly criticised it, particularly over financing and IP issues. Nations such as Australia, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States have even described the draft as a ‘step backward.’

Representing Southeast Asia, India emphasised the importance of clearly distinguishing between obligations and responsibilities in the treaty. This distinction is vital to ensuring fairness in the treaty’s implementation between developed and developing nations.

The alternative—national isolationism and self-reliance—proved costly during the pandemic. As the virus spread, countries were compelled to halt international trade and travel, crippling global economies. The pandemic demonstrated that no one is safe unless everyone is safe. Investing in a coordinated response is far more cost-effective than the consequences of inaction.

Looking ahead

A potential solution could involve establishing a network of global mRNA vaccine production facilities. The modular nature of mRNA vaccines allows for rapid response to emerging viruses. Transparency also plays a crucial role. Despite initial hesitations, China eventually shared the genetic sequence of the COVID-19 virus, enabling researchers worldwide to expedite vaccine development.

Constructing these facilities globally would ensure swifter and more equitable vaccine distribution. A global trust, managed by the WHO and funded by willing donors, could cover costs in Africa and the least developed parts of Asia. Meanwhile, national governments might seek support from private entities. Developing new vaccines and investing in pandemic preparedness also demands substantial funding. Pandemic bonds, akin to catastrophe bonds, could be a viable solution, attracting investors with the prospect of high yields during pandemics.

The agreement faces significant challenges in terms of global governance, enforcement, and accountability. Without cooperation from the Global North, the agreement risks being ineffective.