Women’s self-employment on the rise: India has seen a sharp rise in women’s employment, driven largely by the surge in rural self-employment. The latest Periodic Labour Force Survey shows that self-employment increased from 57.6% in 2017–18 to 73.5% in 2023–24, with women accounting for a significant share of this shift. The change signals a structural transition in the labour market, but it also raises a central question: Is women’s self-employment translating into genuine economic and social empowerment?

The evidence is mixed. While own-account work and micro-enterprises are expanding, much of the increase is concentrated among helpers in household enterprises, who now account for 42% of the rise. This category offers limited autonomy, low and uncertain earnings, and little formal protection. The argument centres on whether the current model of self-employment improves long-term productivity or merely reflects a lack of better jobs. With India aiming for Viksit Bharat @2047, the quality of women’s work comes into sharper focus.

READ I Will labour codes weaken job security further?

Women’s self-employment trends show gains

The rise in own-account workers, from 19% to 31.2% in six years, signals a shift towards micro-entrepreneurship. But women’s self-employment remains informal and vulnerable, with limited access to credit, insurance, or skill-building pathways. The increase mirrors distress-led employment in many pockets, driven by stagnant farm wages, low rural job creation, and limited formal opportunities, as noted by recent RBI analyses of rural labour markets.

Against this backdrop, the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana–National Rural Livelihood Mission has emerged as a critical instrument for women-led enterprise formation. The programme has mobilised 10.05 crore rural households into 91.75 lakh Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and federated institutions. Its pillars—social mobilisation, financial inclusion, livelihood diversification, and social inclusion—have deepened women’s economic participation across rural India.

Financial inclusion underpins SHG growth

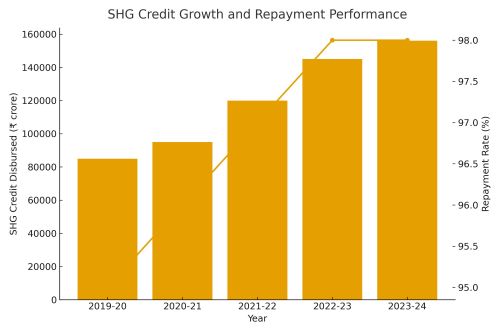

DAY-NRLM’s biggest success has been in creating a dense network of community institutions equipped to handle credit, book-keeping, and enterprise activities. SHGs have built a strong financial track record. By 2022, repayment rates touched 98%, while non-performing assets fell to 2%.

The scale of financial support is rising. Budget allocation for DAY-NRLM increased to ₹19,005 crore in FY 2025–26, a 26% rise compared to the previous year’s revised estimates. By December 2024, banks had disbursed ₹51,697 crore in credit to 21.94 lakh SHGs, signalling strong institutional confidence in the model.

Complementary schemes are strengthening the enterprise ecosystem. The Start-up Village Entrepreneurship Programme (SVEP) supports micro-enterprises in non-farm sectors, while the Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (MKSP) builds capacity for women farmers. Together, these efforts are helping SHG members move beyond subsistence-level activities.

Structural barriers still hold women back

Despite the progress, several constraints reduce the productivity and scale of women-run enterprises. A UNDP (2021) study finds low technology adoption and continued reliance on traditional tools and inputs across producer groups. This limits output quality, market reach, and competitiveness.

Infrastructure gaps, weak market linkages, and socio-cultural norms also persist. Unpaid care work remains the biggest barrier to women’s economic mobility. The Indian Time Use Survey shows women spend nearly 7.3 hours daily on unpaid domestic and caregiving tasks. The ILO (2024) reports that 748 million people globally cite care responsibilities as the primary reason for being outside the labour force—56% of them are women in South Asia.

Operational gaps within SHGs are common. Non-attendance at meetings, irregular record-keeping, and limited follow-through reflect the pressure of household responsibilities. Access to social protection, childcare, early learning centres, and long-term care facilities remains limited in rural India, slowing the transition from group activity to viable enterprise.

Strengthening entrepreneurship through skills

A targeted multi-pronged approach is needed to convert participation into sustained empowerment. The priority is clear: reduce and redistribute unpaid care work, expand community support services, and strengthen skilling pathways. DAY-NRLM’s “Lakhpati Didi” vision can materialise only when skill development is aligned with market needs and local opportunities.

A coordinated effort involving Skill India Digital Hub (SIDH), Self-Help Promoting Institutions, Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), and local NGOs can create specialised skill tracks for SHG members. Continued training for cluster resource persons, banking correspondent sakhis, and SHG leaders can strengthen last-mile delivery.

Improving women’s self-employment outcomes

Improved access to social security will enhance the resilience of women’s enterprises. The e-Shram portal, launched by the Ministry of Labour and Employment, offers a unified platform for 14 social protection schemes, including insurance and skill programmes. Linking DAY-NRLM beneficiaries with the e-Shram database can provide an essential safety net.

Special registration drives can be led by BC sakhis and cluster coordinators. Strong inter-ministerial coordination between rural development, labour, women and child development, and finance ministries can streamline benefits and reduce duplication.

DAY-NRLM remains one of India’s most effective poverty alleviation and women-led enterprise models. But scaling its impact requires structural reforms—better skilling, improved childcare access, stronger financial linkages, and wider social security. Budget allocations must be aligned with human capital investments to raise women’s productivity and labour force participation.

The argument centres on building a policy architecture where women move beyond subsistence-led self-employment into resilient, market-linked enterprises. Achieving this transition is central to India’s ambition of Viksit Bharat @2047.

Dr Ellina Samantroy is Fellow, VV Giri National Labour Institute. Dr Chetana Naskar is India Lead, SHE Changes Climate, New Delhi.