What exactly is Viksit Bharat? Beyond the rhetoric, it is a promise to transform India into a nation that matches the world’s best in prosperity, opportunity, and dignity of life. The idea draws inspiration from the Panch Pran — five guiding commitments: building a developed India, erasing colonial mindset, taking pride in civilisational roots, fostering unity, and instilling civic responsibility. But lofty visions mean little unless they can be defined, measured, and acted upon — a challenge now facing both policymakers and economists.

While politicians may draw inspiration from history and values, economists prefer measurable variables. For the past two years, they have struggled to pin down what Viksit Bharat entails in concrete, quantifiable terms. The Union Budget of February 1, 2025, finally offered a policy framework, listing six goals: zero poverty; universal access to quality school education; affordable, high-quality, and comprehensive healthcare; 100% skilled workforce with meaningful employment; 70% women’s participation in economic activities; and transforming Indian farmers into global food suppliers.

Now comes the harder part — translating these into metrics.

READ I Composite insurance could transform LIC’s growth path

The per capita income benchmark

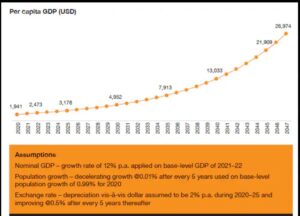

Economists, in the absence of clarity, have so far leaned on a single proxy—per capita income (PCI). To be counted among developed nations by 2047, India’s PCI would need to rise from around $2,500 in 2023 to $17,000. That calls for an annual growth rate of nearly 10%—a steep target, especially when factoring in inflation and population dynamics.

But the new goals widen the lens, demanding a multi-dimensional development strategy. The challenge is to devise indicators that allow progress to be monitored in real time.

Poverty — beyond the global benchmarks

The first Viksit Bharat target—zero poverty—is easier said than measured. Globally, poverty is defined in relative terms; even in New York City, poverty persists by that yardstick. India will need to define an absolute threshold that reflects local context—basic nutrition, clothing, and shelter. This could be benchmarked against the Tendulkar or Multidimensional Poverty Index, but updated to reflect current realities and inflation.

The task is not merely technical. The underlying assumption must be political consensus on what constitutes a minimum dignified life.

School education — quantity vs quality

Universal access to “good quality” education is another Viksit Bharat goal riddled with ambiguity. What defines quality—employability, civic responsibility, or fluency in English?

Should we use Kendriya Vidyalayas, elite private schools, or international boards as a benchmark? Or are state-run schools the more appropriate model? Should employability be the dominant filter, and if so, does English-medium instruction become the default? We will need a composite index that captures infrastructure, teacher competence, curriculum relevance, and student outcomes.

Healthcare — allopathy or ayurveda

On healthcare, defining “high-quality, affordable and comprehensive” remains an open question. Do we benchmark against government hospitals, corporate chains, or global best practices?

India’s health system is pluralistic—Allopathy, Ayurveda, Homeopathy, and Unani co-exist with increasing popularity of wellness practices like yoga. The indicator must account for affordability, accessibility, and outcomes. Perhaps a weighted index combining life expectancy, disease burden, maternal and child health indicators, and out-of-pocket expenditure could serve as a viable composite.

Skill and employment

Skilling 100% of the labour force is perhaps the most dynamic Viksit Bharat goal, especially in an era of rapid technological churn. The Fourth Industrial Revolution—marked by AI, ML, and automation—demands lifelong learning and skill renewal.

Most skilling centres today focus on entry-level vocational training, many trailing behind evolving industry demands. A credible metric here must link certification to employability and income growth, not just course completion. Employment, too, must be qualified—not just by quantity but also the dignity and productivity of jobs.

Women in the workforce

Raising women’s economic participation to 70% would be transformative. Currently, India’s female labour force participation is among the lowest in the G20. In developing countries, women often join the workforce out of necessity; in richer economies, it is a matter of choice.

As fertility rates fall and aspirations rise, policy must navigate a path that supports choice through affordable childcare, parental leave, and safety at the workplace. Any metric will have to capture both participation and the quality of work done—formal vs informal, salaried vs unpaid.

Food security to food sovereignty

India already enjoys food self-sufficiency. But the goal now is to become a food basket for the world. That implies export competitiveness—not just in volumes, but in meeting phytosanitary standards, traceability norms, and carbon footprints of global markets.

To measure progress, India could track the percentage of agri-produce destined for export, net foreign exchange earned from farm exports, and the share of high-value crops like fruits, spices, and processed foods in the basket.

Viksit Bharat: From rhetoric to roadmap

For now, the government has laid out an ambitious direction. Economists must now refine each of these parameters into measurable outcomes. Once that is done, India can move from aspirations to actionable goals—and begin tracking real progress.

Achieving Viksit Bharat by 2047 is not just a slogan. If delivered, it will mark a new chapter in development economics, proving that large, diverse democracies can not only grow fast, but grow equitably.

And for India’s economists, the journey from abstraction to accountability begins now.

Dr Charan Sigh is a Delhi-based economist. He is the chief executive of EGROW Foundation, a Noida-based think tank, and former Non Executive Chairman of Punjab & Sind Bank. He has served as RBI Chair professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.