Indian diplomacy has been under considerable stress in recent weeks, absorbing the pressure of a flurry of high-stakes engagements. These included the Quad foreign ministers meeting in Washington on July 1 and the BRICS summit in Rio de Janeiro on July 6–7, closely following a multi-nation parliamentary outreach aimed at presenting India’s position on the recent terrorist attack originating from Pakistani soil. This sequence of events highlights both India’s rising diplomatic centrality and the increasing difficulty of maintaining strategic autonomy in a world defined by economic coercion and geopolitical competition.

The Rio summit of BRICS yielded two outcomes that have placed India squarely in the glare of strategic scrutiny. The first was a pointed condemnation of what the bloc described as the “weaponisation of civilian nuclear infrastructure”—a diplomacy coated rebuke of the US–Israeli airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities last month. The second was a collective rejection of unilateral tariff measures, reflecting deepening concern over the use of trade policy as a tool of geopolitical assertion. Though the language avoided direct naming, the implications were unmistakable: BRICS is asserting a normative challenge to Western exceptionalism, both in military conduct and trade practice.

READ I BRICS economic goals clash with India’s Quad strategy

Trump’s tariff threats

Washington’s response was immediate. President Donald Trump, announced a sweeping additional 10 percent tariff on any nation aligning with what he termed “anti-American policies of BRICS.” He further warned of a potential 100 percent tariff on countries supporting the bloc’s de-dollarisation agenda. This is nothing but coercive signal. The message to partners was clear: alignment with BRICS could carry tangible costs. Rather even the phrase – partner – must be redefined in the English dictionary.

For India, this escalation introduces a new degree of strategic friction. On the one hand, it is a founding member of BRICS, deeply invested in its potential as a platform for Global South solidarity and multipolar reform. On the other, it is actively engaged in a sensitive and high-stakes trade dialogue with the United States, with expectations of an interim economic agreement by autumn 2025. Its participation in the BRICS communiqué may reflect long-standing commitments to sovereignty, non-intervention, and international law, but it also risks inviting economic penalties that could undermine India’s export competitiveness and investor confidence.

Trade talks and red lines

The trade dialogue with the United States is itself layered with complexity. While India is open to deeper integration on digital trade, clean energy, and critical technologies, there are red lines it cannot cross. Sectors such as agriculture are politically and economically sensitive, and remain non-negotiable in the domestic context. The agricultural sector, in particular, forms the socio-economic backbone of rural India and commands significant electoral weight. Concessions that expose Indian farmers to subsidised American imports could have profound political consequences. Similarly, premature liberalisation of the automotive sector would disrupt an industry that is both labour-intensive and central to India’s manufacturing aspirations under programmes like ‘Make in India’. Negotiating trade convergence while protecting sectoral sovereignty is, therefore, political necessity.

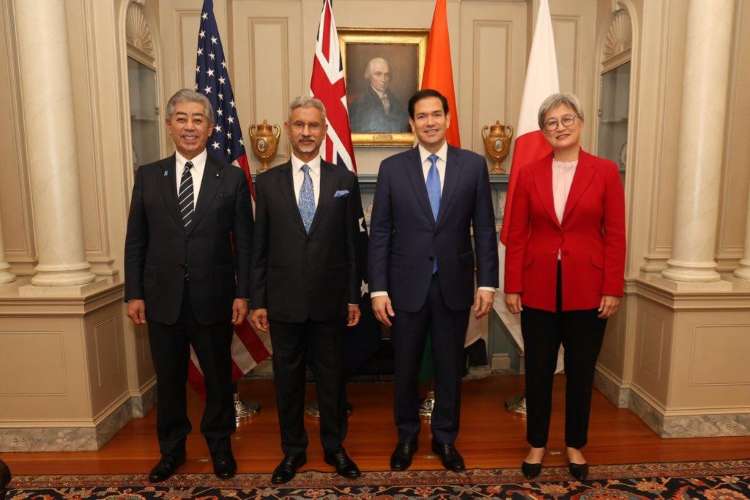

New Delhi’s diplomatic response has so far been defined by calibrated ambiguity. The BRICS statement was firm on principle but avoided naming the United States or Israel directly. In Washington, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar reaffirmed India’s commitment to a rules-based international order while engaging substantively with US counterparts. This twin-track engagement reflects the essence of India’s approach: principled but pragmatic, assertive yet non-confrontational.

Beyond binary alignments

India’s position is shaped by a strategic culture that rejects binary alignments. While deeply engaged in the Quad and committed to Indo-Pacific stability, India does not seek to be tethered to bloc politics. Its engagement with BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the broader Global South is not intended to supplant Western partnerships, but to broaden the avenues through which it can shape global norms.

It is telling that India, while supporting BRICS efforts to diversify financial arrangements, has remained circumspect on de-dollarisation. It has not endorsed Chinese-led monetary alternatives, instead preferring gradual de-risking and deeper cooperation on digital payments and trade finance with multiple partners.

India’s strategic pluralism

This pragmatic pluralism also informs India’s wider foreign policy architecture. It has invested in overlapping minilaterals—such as I2U2 and the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor—while simultaneously deepening its presence in multilateral infrastructure such as the New Development Bank. Its “Act East” engagement, Indo-Pacific maritime strategy, and linkages with Africa and Latin America all point to a country seeking not to choose sides, but to expand its agency.

Yet the space for manoeuvre is narrowing. Trump’s tariff doctrine, even if domestic-rhetoric, the risk of an increasingly transactional and punitive international environment. For India, the potential imposition of tariffs could affect key sectors of the economy at a time when global capital, manufacturing supply chains, and geopolitical influence are being redrawn. The challenge is therefore twofold: to uphold its normative commitments without inviting avoidable costs, and to convey to both BRICS and the US that its strategic autonomy is not a form of fence-sitting, but a coherent doctrine anchored in democratic values, sovereign equality, and institutional reform.

Shaping a new order

India must continue to articulate that its role within BRICS is not ideologically adversarial to the West. Rather, it represents a push for rebalancing and inclusion, not decoupling or confrontation. In doing so, India strengthens its claim as a credible voice for the Global South, while reinforcing its reliability as a partner to the developed world. Its contribution lies not in echoing the rhetoric of power blocs, but in shaping a framework where dialogue remains possible, diversity is institutionalised, and coercion—whether military or economic—is resisted by legal and diplomatic means.

The coming months will test the coherence of this approach. If India can resist the gravitational pull of rigid alignments, protect its economic interests, and remain firm in its normative commitments, it will not simply preserve autonomy—it will begin to define a new model of leadership.

The real question is whether India can demonstrate that strategic autonomy is not an act of hedging, but an act of leadership. The answer may well shape the contours of global governance for the remainder of the twenty-first century.

Srinath Sridharan is a strategic counsel with 25 years experience with leading corporates across diverse sectors including automobiles, e-commerce, advertising and financial services. He understands and ideates on intersection of finance, digital, contextual-finance, consumer, mobility, Urban transformation, and ESG. Actively engaged across growth policy conversations and public policy issues.