The rupee depreciation challenge: Foreign exchange rate reflects the external purchasing power of the domestic currency and is shaped by demand and supply in global transactions. Trade in goods and services, remittances, capital flows and external borrowing influence this balance. In an open economy, exchange rate movements affect inflation, capital inflows and export competitiveness. The exchange rate system has evolved from metal coins to the gold standard and fixed regimes.

Under the gold standard, currencies were pegged to a fixed quantity of gold. After 1944, the Bretton Woods system linked currencies to the US dollar, which remained convertible to gold at $35 per ounce under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund. Persistent US deficits forced the system to unwind, and major economies moved to floating exchange rates through the 1970s.

India followed a fixed exchange rate regime for decades. At independence, the rupee was pegged to the pound sterling, and later to the US dollar. By the 1970s and 1980s, the rupee moved to a currency basket to reflect changing trade patterns. The currency was devalued in 1949, 1966 and 1991, the last during a balance-of-payments crisis.

The decisive shift came in 1993, when India adopted a market-determined exchange rate under a liberalised foreign exchange framework. Since then, the Reserve Bank of India has followed a managed float, intervening only to smooth volatility and not to defend any specific rate. This regime is documented in the RBI’s Annual Reports.

READ I IMF flags rupee flexibility shift as RBI reduces intervention

How the rupee has moved — and why

The rupee has weakened sharply over the decades. It moved from ₹3.30 per dollar in 1947 to ₹7.50 in 1966, and now trades near ₹89–90. In May 2024, it touched ₹83.28. The currency has been among Asia’s weaker performers since 2024, pressured by a stronger dollar and domestic vulnerabilities.

A similar slide had occurred in 2018, during a period of US Federal Reserve rate hikes that pushed most emerging-market currencies lower. India saw an 11–12% depreciation that year. Recent performance has also lagged the Chinese yuan and the Indonesian rupiah, both of which absorbed global shocks more effectively.

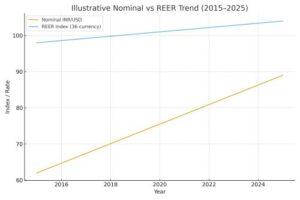

The rupee depreciation is not only a nominal story. The RBI’s Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) often shows the rupee as overvalued, even when it appears weak. This affects export competitiveness and matters for manufacturing.

Rupee depreciation and external pressures

Several factors have converged to push the rupee toward the ₹90 mark. A 50% US tariff on a broad set of Indian exports widened India’s deficit with the US, its largest trading partner. India imports 85% of its crude oil and remains one of the largest importers of gold. Rising prices worsened the current account deficit, raising dollar demand. Net FDI turned negative at –$2.4 billion in September 2025, as reported by the RBI. Foreign portfolio investors have withdrawn $16.5 billion since August 2025.

A stronger dollar, rising global yields and geopolitical tensions have driven investors toward safe-haven assets. The “dollar smile” phenomenon — strong dollar during US growth and global stress — has worked against emerging-market currencies, including the rupee. These forces have kept the rupee under sustained pressure, with analysts expecting further weakness unless inflows strengthen.

RBI intervention and managed float

The RBI has responded through a mix of interventions and liquidity operations. The objective is currency stability, not defence of a specific level. In 2019, the RBI conducted a $5-billion rupee-dollar swap. In February 2025, swap volumes rose to $10 billion. Between November 2024 and November 2025, the RBI sold nearly $50 billion in the spot market to curb volatility.

When the rupee breached ₹88.80, the RBI intervened and later scaled back once markets stabilised. Despite these operations, India still holds $698 billion in reserves as of September 2025 — enough to cover 11 months of imports, based on IMF reserve adequacy norms.

These reserves, combined with large services earnings and remittance inflows, are India’s key shock absorbers. Services exports — led by IT, GCCs and consulting — bring in over $325 billion annually, according to the World Bank. Remittances add another $125–130 billion, the highest in the world.

These flows do not eliminate vulnerability, but they reduce the risk of a disorderly fall.

Exchange rate risks for Indian economy

The rupee depreciation affects sectors unevenly. Imports become costlier. Crude oil, fertilizers and electronics become more expensive, triggering inflationary pressures. Exporters get mixed gains. Low-value exporters benefit, but high-tech sectors dependent on imported components gain little.

Students and households face rising costs. An estimated 759,000 to 1.33 million Indian students studied abroad in 2024. Their expenses rise when the rupee weakens. Remittance-receiving families benefit, as foreign inflows convert into more rupees, providing a cushion against inflation.

Fiscal and monetary policy options

India displays strong macroeconomic fundamentals: 8.2% GDP growth in Q2 FY26, moderate inflation, stable external debt and robust reserves. Yet fundamentals alone cannot shield the rupee from global shocks, tariff actions, structural import dependence and volatile capital flows.

The risk lies not in immediate crisis but in chronic external vulnerability. Weak goods exports, high commodity imports and sensitivity to global cycles create recurring currency pressure.

A stronger rupee depends on more than intervention. India must expand high-value exports, deepen trade agreements, ease logistics, and build supply-chain strength. Reducing import dependence on crude and electronics is essential.

Attracting long-term FDI, rather than volatile portfolio flows, will stabilise the external account. Better hedging tools for firms and MSMEs can limit exposure to sharp swings.

A credible exchange-rate strategy lies in strengthening external fundamentals, not targeting a number.

Dr Ravindran AM is an economist based in Kochi. He has more than three decades of academic and research experience with institutions such as CUSAT, Central University of Kerala, Cabinet Secretariat - New Delhi, and Directorate of Higher Education Pondicherry.