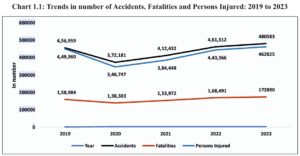

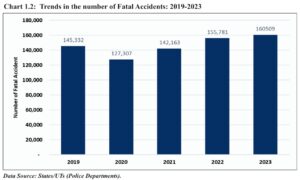

India’s urban mobility crisis has reached a breaking point. The ministry of road transport and highways’ Road Accidents in India 2023 report reveals the grim reality of road safety in the country: 1.73 lakh people died in road crashes last year, the highest ever recorded. Two-wheeler riders made up 44.8% of fatalities, pedestrians 20.4%, and cyclists 2.6%. Pedestrian deaths alone jumped 7.3% from 32,825 in 2022 to 35,221 in 2023.

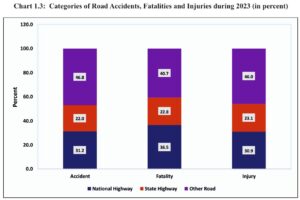

Although rural roads account for 68.5% of road accident deaths, urban roads — just 8.5% of India’s network — bear 31.5% of fatalities. City streets, designed for speed and vehicles, expose the most vulnerable: pedestrians, cyclists, and two-wheeler riders.

READ I Affordable housing the real test for emerging India

Road safety: Policy choices, not destiny

These deaths are not inevitable by-products of growth, but the consequence of misplaced policy and design priorities that ignored road safety. For decades, India has built roads to move cars, not people. The emphasis has been on traffic flow, lane expansion, and vehicle speed, with little thought for inclusivity or safety. The result: high-speed corridors that endanger walkers and riders in already congested and polluted cities.

Pedestrian safety illustrates the failure most starkly. An IIT Delhi study shows 1.5 lakh pedestrians were killed between 2019 and 2023, nearly one in five road deaths. These victims include children walking to school and elderly people trying to reach bus stops. Most Indian cities lack continuous footpaths, safe crossings, or speed-calmed zones. In Ahmedabad, where 535 people died in road crashes in 2023, pedestrians accounted for 44% of fatalities, with speeding responsible for 96% of cases.

Two-wheelers reflect another side of the problem. They dominate India’s urban roads because safe, affordable public transport is missing. While cheap and flexible, scooters and motorcycles expose riders to the highest risk. MoRTH data confirms that two-wheelers account for the largest share of deaths. Without reliable public transport, dependence on these unsafe modes will persist, reinforcing a cycle of risk.

Pockets of innovation

Change is possible. Cities such as Nagpur, Gurugram, and Pune are experimenting with people-first mobility that emphasises on road safety. Nagpur has redesigned 15–20 km of roads with footpaths, cycle tracks, and signage. Gurugram has piloted a model road with sidewalks, cycle lanes, lighting, and greenery. Pune’s Comprehensive Mobility Plan envisions integrated footpaths and cycle tracks linked to metro corridors by 2054. Odisha is drafting an urban parking policy to reduce private vehicle use.

These are promising but isolated examples. In most cities, footpaths and cycle lanes remain add-ons, not essentials. Global experience shows that designing roads with the Safe Systems approach — which anticipates human error and prioritises safety — saves lives without slowing traffic. For India, with its staggering toll, this is an urgent necessity.

From pilots to policy

Institutional reform is overdue. The Sundar Committee (2007) and the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act (2019) called for a National Road Safety Board to set standards for design, safety, and trauma care. Though the government notified its creation in 2021, the board remains largely non-functional. In May 2025, the Supreme Court directed the government to operationalise it within six months. A strong central authority is critical to end fragmentation and enforce uniform standards.

Equally vital is a shift in mobility planning itself. Cities cannot depend on private vehicles and two-wheelers. Public transport — metros, bus rapid transit, and multi-modal hubs — must form the backbone of urban mobility, supported by walking and cycling for last-mile access. Reliable public transport is not just an infrastructure investment but also a safety measure, reducing exposure to high-risk modes.

Engineering and enforcement alone will not suffice. India must move away from the prevailing road culture where the largest vehicle dictates right of way. Changing attitudes requires both policy and public awareness. MoRTH’s 2023 figures show that without systemic reform, cities will continue sacrificing tens of thousands of lives each year.

Piecemeal projects cannot replace a national framework that integrates safety, pedestrian rights, public transport, and climate goals. The real task is not just to redesign streets but to redefine mobility itself — shifting from car-centric growth to a humane, inclusive, and sustainable model.

Simi TB is Assistant policy analyst at CUTS international.