India’s automobile industry stands on the cusp of a transformation. Rising pollution, volatile fuel prices, and mounting climate concerns are converging to make electric vehicles not just an alternative but a necessity. EV adoption promises to cut emissions, reduce fossil fuel dependence, and lower import bills, while spurring innovation, job creation, and investment. Together, these factors could position India as a leader in sustainable mobility.

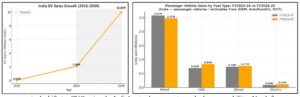

The electric vehicles market in India has expanded rapidly in line with NITI Aayog’s target of electrifying 30% of vehicles by 2030. Global EV sales surged from 0.9 million units in 2016 to nearly 19 million in 2024 — a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 45.8%. India has outpaced this with a 59.4% CAGR over the same period, moving from 50,000 units in 2016 to 2.08 million in 2024. Although EVs accounted for only 2–3% of new car sales — below the global average of 5% — India remains the fastest-growing large EV market.

NITI Aayog projects a 49% CAGR between 2022 and 2030, reaching 10 million annual sales by decade-end. Encouragingly, adoption is spreading from metros to Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, signalling a broader social and economic shift. Passenger vehicle data for FY2024–25 show this transition gaining traction. While petrol cars dipped from 2.57 million to 2.47 million units, EV sales grew 50%, from 80,000 to 120,000 units. The numbers remain small, but the trajectory is clear: cleaner mobility is no longer a niche trend.

READ I India-China trade: NITI Aayog hints at a pragmatic turn

Why electric vehicles transition matters

The case for electrification extends beyond convenience or cost. Transport contributes about 14% of India’s total CO₂ emissions, and vehicular pollution drives air quality in major cities to hazardous levels. Meanwhile, oil imports account for over 85% of India’s crude consumption, burdening the trade balance.

Government incentives—tax breaks, subsidies, and fee waivers—have boosted sales, but the rationale is strategic. A 2023 NITI Aayog perception survey found that 75% of EV buyers cited fuel savings as the top motivator, followed by pollution reduction. In short, EVs align environmental necessity with economic logic.

The bottlenecks: Cost and infrastructure

India’s electric vehicles revolution faces familiar hurdles. High upfront costs, driven by expensive lithium-ion batteries, remain the biggest deterrent. These batteries also add weight and affect vehicle range.

The lack of adequate charging infrastructure compounds the problem. As of mid-2025, India had only around 12,000 public charging stations—grossly insufficient for mass adoption. Rural and semi-urban regions are particularly underserved, making EV ownership impractical outside major cities.

Awareness gaps and concerns about reliability, battery life, and resale value persist. Dealers and financiers remain cautious, dampening consumer confidence. Unless infrastructure and financing evolve together, achieving 2030 targets will be difficult.

Government push: Policy and incentives

Public policy has been central to India’s electric vehicles push. Schemes like FAME I and II subsidize vehicle purchases and charging infrastructure, while states including Delhi, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu offer additional tax waivers and subsidies. The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for Advanced Chemistry Cells is encouraging domestic battery manufacturing, reducing import dependence.

By mid-2025, 29 states and Union Territories had adopted EV policies aimed at lowering imports, expanding manufacturing, and creating jobs. NITI Aayog’s “Shoonya” campaign has promoted zero-emission transport, especially in delivery and ride-hailing sectors.

A further boost came from the GST Council’s September 2025 decision to retain the 5% GST rate on EVs while reducing taxes on small cars, two-wheelers, and auto components to 18%. This move will lower costs across the supply chain and make EVs more competitive.

Cleaner air, lower costs

One of the strongest arguments for electric vehicles lies in their environmental payoff. The Central Pollution Control Board estimates that vehicles contribute nearly 30% of PM2.5 levels in cities such as Delhi and Mumbai. Replacing internal combustion engines with EVs could sharply reduce urban pollution and improve public health.

Battery prices are projected to fall by almost 60% within five years, according to BloombergNEF, narrowing the price gap with petrol vehicles. With improving technology and economies of scale, affordability will no longer be a major obstacle.

Two- and three-wheelers are leading the charge. E-rickshaws, delivery scooters, and shared mobility fleets are rapidly electrifying. Firms such as Tata Motors, Ola Electric, Ather, MG Motor, and Maruti Suzuki have expanded their EV portfolios, from the Nexon and Tiago EVs to the Ola S1 range.

Learning from global leaders

India’s progress is impressive but still trails global leaders. China dominates the EV supply chain, controlling over 70% of global battery manufacturing and offering vast charging networks. Norway, at the other extreme, has achieved over 80% EV penetration in new car sales through a mix of tax waivers and infrastructure investment.

Electric bus fleets in Indian cities like Delhi and Bengaluru are expanding, but the penetration of electric trucks and long-haul vehicles remains limited. Accelerating this segment will be vital if India is to meet its 2030 target of 30% electrification.

Public sentiment and social shift

EVs are increasingly part of urban aspiration. The NITI Aayog survey shows 87% of respondents view EVs positively, citing lower operating costs and environmental gains. Young professionals between 18 and 35 are leading adoption, attracted by the combination of tech-driven design, convenience, and climate awareness.

Still, concerns linger over charging access, upfront costs, and long-term performance. Overcoming these anxieties will require trust built through transparency, warranty support, and widespread charging visibility.

The road to a greener future

India’s electric vehicles future is within reach but not guaranteed. The sector needs a coordinated push—affordable finance, resilient infrastructure, and long-term policy clarity. Private players must invest in R&D, while the government must ensure grid readiness and localize critical supply chains.

If India sustains its current pace, the outcome will be transformative. Cleaner cities, reduced oil imports, and a new generation of green jobs could redefine India’s economic landscape.

The road ahead may be long, but the direction is unmistakable. Electric mobility is not merely a technological shift—it is India’s route to a cleaner, more self-reliant, and globally competitive future.

Nistha Thakur is a research scholar, and Amit Singh Khokhar Assistant Professor at Delhi Skill and Entrepreneurship University.