Delhi air pollution: Delhi’s air quality crisis has reached a scale that demands structural solutions, not seasonal firefighting. Air Quality Index readings now stay above 400 through winter, far beyond the hazardous threshold of 300. The city’s PM2.5 levels routinely touch 200–300 µg/m³ — forty to sixty times the WHO’s annual limit of 5 µg/m³. Health risks have mounted with it: the WHO estimates that 2.2 million children in Delhi show signs of irreversible lung damage.

Much of Delhi’s winter pollution is hyper-local, from vehicles, construction and industry. But crop residue burning in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh remains a persistent seasonal spike, contributing 8–15% of peak pollution. India generates 500–550 million tonnes of agricultural residues annually, and almost 40% comes from these three states. Rice straw alone contributes 150–180 million tonnes, with 70–80% burned openly for lack of alternatives. The scale of the problem suggests that punitive action cannot substitute for viable, affordable options for farmers.

READ | Rupee depreciation: The real drivers of India’s currency fall

Farmers burn because economics forces their hand. The gap between paddy harvesting and wheat sowing is just 15–20 days, leaving little time for collection or processing. Incorporating straw back into the soil requires machinery that costs ₹2–3 lakh — beyond the reach of most small and marginal farmers. Without organised markets for residues, farmers treat them as waste, not assets. The issue is not unwillingness but the absence of cost-effective pathways to remove or monetise residue.

Biomass pellets as a scalable market solution

Turning residues into biomass pellets and briquettes offers a workable market model. Their calorific value of 4,100–4,300 kcal/kg rivals that of lower-grade coal. India’s biomass pellet market is expanding rapidly and is expected to reach ₹18,500 crore by 2028, helped by mandates requiring power plants to co-fire 5–7% biomass with coal. These rules create an assured market worth ₹8,000–10,000 crore annually.

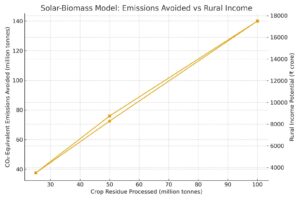

The climate benefits are substantial. Replacing coal with biomass can cut CO₂ emissions by 85–90%. Preventing open burning avoids another 1.3–1.5 tonnes of CO₂-equivalent per tonne of residue. Processing 100 million tonnes of residues could prevent 130–150 million tonnes of emissions a year. In a single stroke, the country addresses air pollution, energy transition and farm distress.

Solar-powered processing: Making the economics work

Powering pelletisation units through the PM-KUSUM programme provides another economic lever. The scheme’s budget of ₹2,600 crore for 2025–26 signals the government’s push for decentralised rural solar capacity.

Solar-powered pellet units reduce operating costs by up to 70%, enabling pellet prices in the ₹8–10/kg range, close to coal’s ₹6–8/kg. A 50 kW unit can operate for 6–8 hours a day, supported by battery storage for evening production. The economics are attractive. A unit processing 10–15 tonnes daily can earn ₹15–20 lakh a year, generating ₹8–12 lakh in net profits with a payback of 4–6 years. Rural entrepreneurship of this kind aligns with India’s Viksit Bharat 2047 vision.

A major hurdle is land availability. A vertical infrastructure model addresses this by compressing operations into a three-tier structure: the ground level for pellet machinery, the second tier for batteries and control systems, and the rooftop for solar panels. This reduces land use by 70–80% while ensuring efficient operations, making it replicable across districts with limited land availability.

Delhi air pollution: Policy support

Large-scale adoption will need policy clarity and financial support. The first requirement is a strengthened KUSUM framework, with targeted subsidies of 10–15% to attract rural entrepreneurs. A second step is to build commodity exchanges for biomass pellets and guarantee structured procurement by power plants. Incentives for global technology transfer would help upgrade pellet quality and improve plant efficiency. Collateral-free loans up to ₹25 lakh can unlock investment for farmer-producer organisations and rural start-ups.

Operational risks remain, but all are manageable. Solar-assisted drying can bring moisture levels down to the optimal 8–10%, improving pellet quality. Certification centres can standardise output and prevent adulteration. High upfront costs can be addressed through lease-to-own models or collective investment by FPOs. Seasonal availability can be handled through structured storage systems that limit microbial degradation.

India’s annual stubble-burning crisis is a symptom of deeper structural constraints in agriculture and energy markets. A solar-powered biomass ecosystem offers a rare convergence of incentives: it cleans Delhi’s air, expands rural incomes, reduces coal dependence and prevents up to 150 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions annually. With potential rural incomes of ₹15,000–20,000 crore, the approach turns waste into value and aligns local incentives with global climate goals.

The government, private sector and farming communities now have a viable model that is technologically ready and commercially credible. Delhi’s severe winter pollution spikes can no longer be treated as an inevitable annual event. The country faces a clear choice: persist with an avoidable crisis, or back a solution that creates cleaner air, resilient livelihoods and a pathway to sustainable rural growth.

Dr Deepa Palathingal is Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Christ University, Delhi NCR Campus. Yuvraj Tandon and Siddharth Jogdand are BSc Economics & Mathematics students.