The United Nations General Assembly on December 12, 2012 unanimously endorsed a resolution urging all member countries to ensure progress toward universal health coverage. Everyone everywhere should have access to affordable healthcare – an essential requirement for international development and fundamental human rights. Universal health coverage is a health system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured of access to healthcare.

The Universal Health Coverage Day is an opportunity to raise awareness of the need for strong and resilient health systems and access to healthcare. UHC advocates raise stories for health, call on leaders to make more significant and innovative investments in health, and remind the world that ‘Health for All’ is imperative to create a just world.

According to World Health Organization, UHC is about all the individuals and communities receiving the essential health services they need without financial hardship. It includes the full spectrum of essential, quality health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care across the life course.

READ I Fighting heavy odds: Corporate influence over policy weighs on India’s public health system

Health inequity is a critical barrier to UHC. It is the systematic differences in the health status and access to healthcare for different population groups within the country and between countries. Marginalised population groups experience worse health and increased difficulty accessing healthcare due to the systems that influence their lives. In addition, developed and developing countries suffer due to health inequity.

Australia presents a unique service of universal health coverage for all its citizens among developed countries. The Australian universal public health insurance program (Medicare) is financed through general tax revenue and a government levy. Enrolment is automatic for all citizens who receive free public hospital care and substantial coverage for physician services, pharmaceuticals, and certain other services.

Even in developed countries such as Australia, indigenous peoples dying from cardiovascular disease is 1.5 times that of their non-Indigenous counterparts. Despite this, indigenous peoples are often prevented from accessing critical services due to a range of barriers, including the high cost of healthcare, experiences of discrimination and racism and poor communication with healthcare professionals.

Australians enjoy a higher life expectancy of 82.90 years (2019). However, the aboriginal and Torres Strait islander population born in 2015–2017, life expectancy was estimated to be 8.6 years lower than that of the general population.

READ I Covid-19 lessons: Public health system must offer free drugs, diagnostics

Right to universal health coverage

In contrast, Indian constitution obliges the government to ensure “right to health” for all. Theoretically, all Indian citizens can get free outpatient and inpatient care at government facilities. However, under India’s decentralised approach to healthcare delivery, the states are primarily responsible for organising health services.

Because of lack of resources, staff shortages and supplies at government facilities, many households seek care from private providers and pay out-of-pocket for low-income population groups, the government recently launched the tax-financed National Health Protection Scheme (Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana, or PMJAY), which entitles them to cashless secondary and tertiary care at private facilities.

India is among the countries having the lowest public healthcare budgets in the world. The public healthcare system in the country gets just 1.26% of the GDP. Oxfam India’s Inequality Report 2021 narrated India’s unequal healthcare story. Data shows that 65.7% of the households belonging to the general category have access to improved, non-shared sanitation facilities while only 25.9% of scheduled tribe (ST) households have improved, non-shared sanitation facilities.

As a result, 12.6% more children are stunted in Scheduled Castes (SC) households than those in households belonging to the general category. Furthermore, the chances of a child dying before his/her fifth birthday are three times higher for the bottom 20% of the population compared to the top 20%.

The Oxfam report provides a comprehensive analysis of health outcomes across different socioeconomic groups to gauge the level of health inequality that persists in the country. For example, the report shows the general category performs better than scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Hindus perform better than Muslims, the rich perform better than the poor, men are better off than women, and the urban population is better off than the rural population on various health indicators.

Institutional births and access to food supplements under ICDS are 10% less for Muslim households than for Hindu households; 8% fewer children are immunised in Muslim households. Further, reduced health budget allocations in 2021 disproportionately affect marginalised groups.

READ I Universal health insurance a distant dream without healthcare reforms

Lessons from Covid-19 pandemic

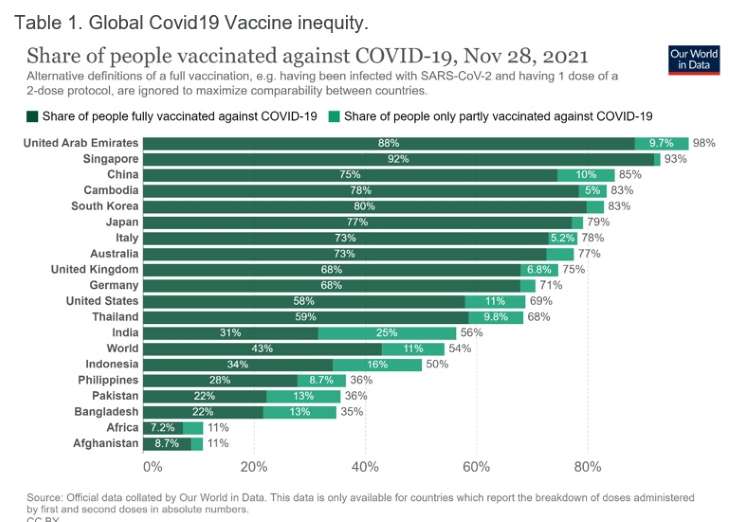

Covid-19 has further exacerbated health inequalities. As we enter the third year of the pandemic, the glaring inadequacy of the healthcare system to cope with the health care needs of most in need stand out. Global Covid-19 vaccine inequity is a glaring example of health inequity between countries.

As a lesson to be learned from the pandemic, we have no choice but to strengthen our health systems to ensure they are equitable, resilient, and capable of meeting everyone’s needs. There is now an urgent opportunity and need for more and better investments for strengthening health systems grounded in primary healthcare – to ensure that no one is left behind. In addition, we must hold elected leaders accountable for achieving the promise of health for all as part of Covid-19 response and recovery strategies.

Countries need to scale up their investments in essential public health functions—those core public health functions that require collective action and can only be funded by governments or risk significant market failures.

These include policy making based on evidence, communication including risk communication and community outreach to empower individuals and families to manage better their health, information systems, data analysis, and surveillance, laboratory capacity for testing; regulation for quality products and healthy behaviours, and subsidies to public health institutes and programmes.

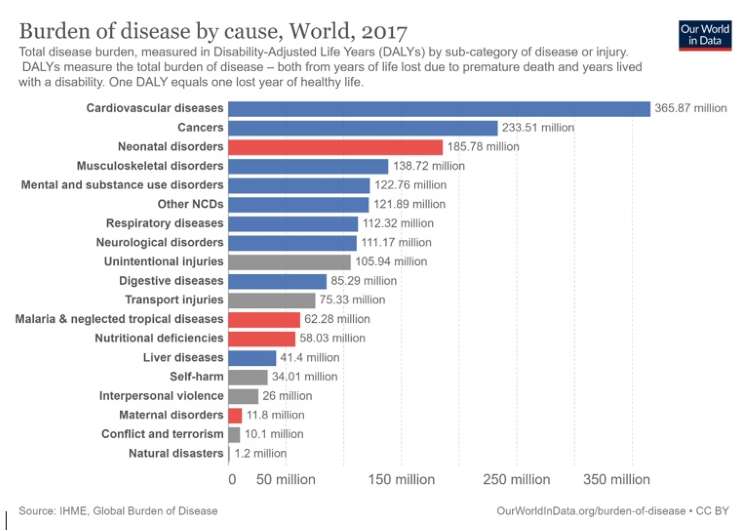

The data on burden of disease by cause also indicates the extent of health inequity — total disease burden, measured in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) by sub-category of disease or injury. DALYs measure the total Burden of disease – both from years of life lost due to premature death and years lived with a disability. One DALY equals one lost year of healthy life.

To prevent future pandemics and achieve health and wellbeing for all by 2030, we must prioritise equity – investing more in health and allocating resources efficiently and equitably according to need.

The delivery of essential health services requires adequate and competent health care workers with optimal skills mix at facility, outreach and community level, and equitably distributed, adequately supported, and enjoy decent work. UHC strategies enable everyone to access the services that address the most significant causes of disease and death and ensure that those services’ quality is good enough to improve the health of the people who receive them.

Protecting people from the financial consequences of paying for health services out of their own pockets reduces the risk that people will be pushed into poverty because unexpected illness requires them to use up their life savings, sell assets, or borrow – destroying their futures and often those of their children.

Achieving UHC is one of the targets the world’s nations set when adopting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. Countries reaffirmed this commitment at the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on UHC in 2019. Countries that progress towards UHC will progress towards the other health-related targets and the other goals. Good health allows children to learn and adults to earn, helps people escape from poverty and provides the basis for long-term economic development.

Many countries are already making progress towards UHC, although everywhere the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the availability and the ability of health systems to provide undisrupted health services. All countries can move more rapidly towards UHC despite the setbacks of the COVID-19 pandemic or to maintain the gains they have already made. However, in countries where health services have traditionally been accessible and affordable, governments are finding it increasingly difficult to respond to the ever-growing health needs of the populations and the increasing costs of health services.

Moving towards UHC requires strengthening health systems in all countries. When people have to pay most of the cost for health services out of their own pockets, the poor are often unable to obtain many of the services they need, and even the rich may be exposed to financial hardship in the event of severe or long-term illness. Pooling funds from compulsory funding sources (such as government tax revenues) can spread the financial risks of illness across a population.

Improving health service coverage and health outcomes depends on health care workers’ availability, accessibility, and capacity to deliver quality people-centred integrated care. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically demonstrated the invaluable role of the health and care workforce and the importance of expanding investments in this area.

To meet the health workforce requirements of the SDGs and UHC targets, over 18 million additional health workers are needed by 2030. Gaps in the supply of and demand for health workers are concentrated in low- and lower-middle-income countries. The growing demand for health workers is projected to add an estimated 40 million health sector jobs to the global economy by 2030.

Investments are needed from both public and private sectors in health worker education and the creation and filling of funded positions in the health sector and the health economy. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, which has initially affected the health workforce disproportionately, has highlighted the need to protect health and care workers, prioritise investment in their education and employment, and leverage partnerships to provide them with decent working conditions.

UHC emphasises what services are covered and how they are funded, managed, and delivered. A fundamental shift in service delivery is needed such that services are integrated and focused on the needs of people and communities.

This includes reorienting health services to ensure that care is provided in the most appropriate setting, with the right balance between out- and inpatient care and strengthening the coordination of care. Health services, including traditional and complementary medicine services, organised around the comprehensive needs and expectations of people and communities, will help empower them to take a more active role in their health and health system.

Investments in quality primary health care will be the cornerstone for achieving UHC. According to WHO, achieving UHC requires multiple approaches. A primary health care approach focuses on organising and strengthening health systems so that people can access services for their health and wellbeing based on their needs and preferences, at the earliest and in their everyday environments.

UHC entails comprehensive, integrated health services that embrace primary care and public health goods and functions as central pieces. Multi-sectoral policies and actions to address the social and structural determinants of health, and engaging and empowering individuals, families, and communities for increased social participation and enhanced self-care and self-reliance in health.

The Covid-19 pandemic forced world nations to rapidly scale up investment in essential public health functions. The core public health functions require collective action and can only be funded by governments as there is significant risk of market failures. These include policy making based on evidence, communication including risk communication and community outreach to empower individuals and families to manage better their health, information systems, data analysis, and surveillance, laboratory capacity for testing; regulation for quality products and healthy behaviours, and subsidies to public health institutes and programmes.

References:

WHO (2021) Universal Health Coverage.

Oxfam India (2021) Inequality Report 2021: India’s Unequal Healthcare Story.

Mathieu, E., Ritchie, H., Ortiz-Ospina, E. et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations.

Nat Hum Behav (2021) Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) – Burden of Disease study.

Dr Joe Thomas is Global Public Health Chair at Sustainable Policy Solutions Foundation, a policy think tank based in New Delhi. He is also Professor of Public Health at Institute of Health and Management, Victoria, Australia. Opinions expressed in this article are personal.