It has been a decade since India introduced the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, a stringent law to protect minors from sexual abuse. While the number of POSCO cases is rising, the conviction rate in such cases is dismally low, says a new report. This may be a reflection of the larger crisis of delays that plague the country’s justice system, but the cases registered under the Act have seen a high percentage of pendency, says ‘A Decade of POCSO’, a report prepared by Delhi-based think tank Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. The study was done in collaboration with the Justice Reform (DE JURE) programme of the World Bank.

India has over 44 crore children and child sexual abuse continues to be a serious and widespread issue in the country which is expected to become the most populous nation. The inability to prevent abuse shows the justice system in poor light.

READ | Inked in India: History of fountain pen, and the policies that killed it

Legal system not equipped to handle POSCO cases

While the legal system in India may have flaws to be fixed, part of the blame should go to the society that stigmatise abuse, forcing children and guardians not to report abuse cases. Other reasons for the tardy progress of POSCO cases are communication gap between children and parents, community denial, and lengthy legal procedures. Studies have highlighted that such trauma leads to psychological and emotional disorders which children may never overcome.

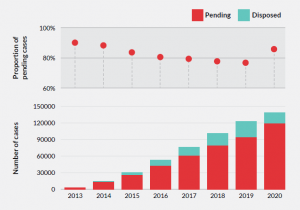

Pending cases

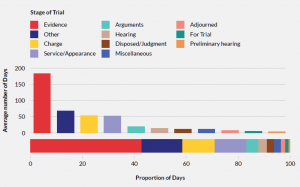

It is often said that justice delayed is justice denied. Slow pace of investigation by the police and delay in depositing samples with forensic laboratories contribute to the piling up of cases. For more than a third of POCSO cases, investigation takes more than six months.

The study found that cases are also slowed by transfers from one court to another. Since POCSO cases are supposed to be tried by special courts, the transfers mean either an administrative mismanagement or wrongful appreciation of facts by the police. While the percentage of transfers out of total disposals was around one in 10, the proportion is rising gradually. Transfers generally lead to unnecessary delays in the trial process.

According to the analysis, the average case length has increased from year to year in states such as Assam, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Himachal Pradesh. This shows that most cases being disposed of are those pending for multiple years. Of the 22,625 cases disposed of in 2018, 45.63% were done in less than one year, 29.67% in one-two years, 13.54% in two-three years and 11.16% in more than three years.

Several other issues hinder justice in child abuse cases. In most cases, there is a lack of support persons. Special courts have not been designated in all districts, and the number of special public prosecutors appointed specifically for POCSO cases is also very low. As of 2022, 408 POCSO courts have been set up in 28 states as part of the government’s Fast Track Special Court’s Scheme.

Key takeaways from the report

On November 14, 2022, POCSO Act completed 10 years. The report found that 43.44% of the trials end in acquittals and nearly 14% lead to conviction. What is more disheartening is the fact that in a number of cases studied extensively, the accused were known to the victims and some were even family members.

Earlier, data carried out by the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) in 2021, also reported that the accused was a person known to the victim in 96% of cases filed under POCSO. Children in the age group of 15-18 years were more prone to sexual abuse. Among the accused in these cases, 11.6% were between 19-25 years of age, and this decreased with increasing age.

READ | Inflation cools, but RBI may continue with interest rate hikes

The study found that there are several states where the gap between acquittal and convictions was huge. For instance, in Andhra Pradesh, acquittals were seven times more than convictions, while in West Bengal it was five times. This is in stark contrast to Kerala where the gap between acquittal and conviction is not very high with acquittals constituting 20.5% of the total cases and convictions constituting 16.49%. National capital Delhi has the highest number of POCSO trials. Districts with the highest number of pending and disposed POCSO trials are Namchi in Sikkim, Central Delhi, Medak (Telangana) and West Garo Hills (Meghalaya).

The report also has several recommendations to strengthen the legal system so that it can be made more effective. A just system can prevent violence against children and ensure that when violence occurs, children get effective redressal. Policymakers have long suggested that the government must reduce the age of consent from 18 to 16 years with adequate safeguards. In fact, before making any substantive amendments to the Act, public consultations with domain experts must be undertaken. Also, there is a dire need to make POCSO courts functional by speeding up of the appointment of adequately trained special public prosecutors for child abuse cases.