Satellite internet was expected to usher in a new phase of digital freedom in India, especially in regions where fibre and mobile networks remain patchy. Those expectations dimmed when Starlink announced a monthly tariff of ₹8,600, along with a one-time terminal cost of ₹34,000, for residential users. Although the company withdrew these figures, calling them a glitch, the glimpse triggered a national debate. India has become accustomed to some of the world’s lowest data prices since 2016, and any hint of premium pricing raises questions about digital inclusion.

The concerns are legitimate. India’s data revolution succeeded not because of technology alone but because connectivity was cheap and abundant. The IMF, TRAI, and global trackers have consistently shown that India offers some of the most affordable mobile data per gigabyte in the world. Against this backdrop, satellite tariffs that resemble Western markets appear unrealistic for mass adoption. Yet the controversy over Starlink’s pricing has also drawn attention to a deeper set of issues that will decide whether satellite broadband becomes a transformative tool or remains a narrow, niche service.

READ | What does Australia’s social media ban really mean

India’s internet base is large, but gaps are deep

India now has between 806 million and 886 million internet users, according to DataReportal and IAMAI–Kantar. This translates to 55–58% penetration, far below the global average of 73.2% as reported by the International Telecommunication Union. The remaining population lives mainly in geographies where connectivity is not commercially viable — Himalayan districts, desert belts, islands, tribal regions, and dispersed rural settlements.

Satellite broadband promises to reach these inaccessible zones. Low-Earth-orbit (LEO) networks like Starlink provide lower latency and better reliability than traditional geostationary satellites. For remote schools, clinics, agriculture clusters, and disaster-prone regions, such technology can be a lifeline. As earlier Policy Circle analysis noted, digital public services will remain incomplete unless the poorest and most remote areas are connected.

But the geography of exclusion is not the only challenge. India’s affordability benchmark is so low that even moderate satellite prices could deter adoption among rural users. The premium that satellite broadband commands globally cannot simply be transplanted into a country where most households spend only a sliver of their income on data.

Starlink debate masks a bigger story

Focusing solely on Starlink misses the larger reality that India now has an emerging competitive satellite-broadband ecosystem. OneWeb, backed by Bharti Global, already has a near-complete LEO constellation in partnership with the UK government and Eutelsat. It is positioned to become India’s first licensed LEO broadband operator under Indian regulatory norms. JioSpaceFiber, unveiled at the India Mobile Congress, aims to leverage Reliance’s distribution network to bring satellite internet to remote villages at more accessible price points. ISRO, through GSAT systems and the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe), is also facilitating private participation in satellite broadband.

This competitive scene is not just incidental. It shapes the regulatory environment, pricing strategies, and commercial viability of all players entering the market. Domestic firms have an advantage in distribution, compliance, and political support, while Starlink faces stricter scrutiny as a foreign technology operator. In practical terms, Starlink may not be able to set prices unilaterally or act as the dominant player in a sector that the government sees as critical for long-term strategic autonomy.

Push for atmanirbhar satellite infrastructure

India’s Space Policy 2023 has redrawn the rules of the game. The policy encourages private players to build, own, and operate satellites, ground stations, and user equipment. It also signals a shift towards domestic manufacturing of terminals and Indian-controlled satellite constellations. In this environment, licensing, spectrum allocation, and security norms are likely to favour models that strengthen India’s technological sovereignty.

This policy thrust explains the deliberate pace of regulatory approvals. Satellite spectrum in the Ku and Ka bands has not been fully allocated. Security and monitoring requirements for LEO operators are still being harmonised by the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) and TRAI. The process is cautious by design. India seeks to avoid overdependence on any foreign player for critical communications infrastructure.

Geopolitical risks add another layer of caution

There is also a geopolitical dimension that the public debate often overlooks. Starlink’s role in the Ukraine conflict, and controversies surrounding its operation during regional blackouts in the Middle East, have alerted governments worldwide to the risks of private satellite networks operating across borders. Communication infrastructure, once space-based, becomes harder to monitor or control at moments of national security.

India’s regulatory caution must be viewed in this light. Satellite broadband is not only about consumer access; it is also about sovereignty, surveillance, disaster response capability, and cyber resilience. Policymakers are unlikely to relax norms until they are satisfied that foreign satellite networks can be monitored and governed in compliance with Indian law.

Satellite internet may scale first in Middle India

The assumption that satellite internet will spread first among the rural poor may not hold. Several telecom consultancies and CRISIL analysts suggest that the earliest real commercial market lies in “middle India” — tier-3 towns, highway logistics hubs, renewable-energy farms, mining districts, tourism belts, and semi-urban MSME zones. These areas are too sparse or rugged for reliable fibre but rich enough to pay for stable high-speed connectivity. They also house industries where downtime is costly.

This segment could generate enough demand to justify local gateways, lower equipment costs, and create economies of scale. As prices fall, satellite broadband could gradually move deeper into rural India, aided by targeted universal service subsidies.

Prices will fall, but policy must move first

Satellite broadband can only become affordable at scale if India accelerates spectrum decisions, eases licensing norms, and encourages domestic terminal manufacturing. These steps could reduce hardware costs and bring down subscription prices. Global experience shows that satellite internet prices fall sharply once constellations stabilise and user density increases. India offers a market large enough for such scale economies.

But technology alone will not bridge the gap. A clear satellite-spectrum framework, efficient coordination between IN-SPACe, DoT, and TRAI, and transparent security norms are essential. Without these reforms, even domestic satellite players may struggle to achieve commercial viability.

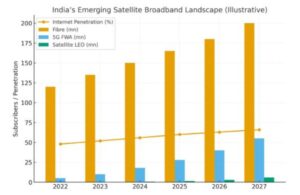

India’s broadband future will rest on a hybrid model. Fibre will serve dense cities, 5G will provide mobility, fixed wireless access will fill suburban gaps, and satellite broadband will connect places that the market has ignored for decades. The goal is not disruption but expansion. Satellite internet can illuminate regions that have long remained in digital darkness, but only if regulation encourages competition, ensures affordability, and aligns with India’s strategic priorities.

Satellite broadband may not revolutionise India’s urban internet. But it can complete the digital map — and that may prove to be the most valuable disruption of all.