India wants its biggest plastic polluters to clean up their mess but new rules introduced in February 2022 have done little to reduce plastic pollution. Only a proportion of producers, importers and brand owners have registered on a centralised portal that would track their plastic collection and recycling targets. While these targets are set by the government, they are based on the self-declared volume of plastic manufactured or imported by those brands.

Further, achievement of these targets will be certified by recyclers which might leave room for corruption. Companies also have the option of purchasing credits if they fail to meet their targets, which might lead to lax implementation. In effect, experts say, the rules will do little to end hazardous plastic waste.

In February 2022, years after conceptualising Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for plastic through the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016, India notified guidelines for the policy. Based on the ‘polluter pays’ principle, the guidelines lay down responsibilities of all stakeholders engaged in the plastic industry and fines for violations.

READ I Push to gig economy can solve India’s jobless growth riddle

The guidelines cover producers, importers and brand owners (online platforms, supermarkets, retail chains) or PIBOs of plastic as well as plastic waste processors. Among the categories of plastic to be collected and recycled under EPR are rigid packaging, flexible packaging of single layer or multilayer plastic sheets such as plastic sachets or pouches, multilayer plastic packaging and carry bags made of compostable plastic.

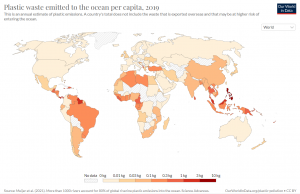

India is the fifth largest generator of plastic waste in the world. It banned certain single-use plastic products from July 1, but that ban has largely been unsuccessful, our reporting from Mumbai, Delhi and Bengaluru showed. In the second part of this series on controlling plastic pollution, we explore why India’s EPR rules fall short.

Plastic pollution thrives

Every packet of chips, shampoo sachet or chocolate wrapper you discard is made up of a type of plastic that may not be recyclable. Estimates say 43% of manufactured plastic in India is used for packaging purposes, and is mostly single-use plastic. However, packaging plastic was not included in the list of products India banned in July 2022 and the onus was put on companies to recycle it under EPR.

The estimated market size of India’s plastic industry stands at Rs 7.1 lakh crore ($96 billion) as of 2021-22 and it employs more than 4 million people, according to the Plastic Industry Status Report 2021, by PlastIndia Foundation, a body of the major associations, organisations, and institutions connected with plastics. In 2021-22, India’s plastic demand was 20.89 million tonnes which is projected to exceed 22 million tonnes by 2023, the report said, adding that the plastic industry claims to recycle more than 60% of plastic waste generated after a product is consumed and its packaging discarded.

Plastics are categorised into seven categories and not all products are recyclable. For instance, while plastic bottles, which fall into the PET category, are recyclable, plastic bags of chips, shampoo sachets and chocolate wrappers are not. These packets, sachets or wrappers are very likely made of multilayer plastic (MLP) or plastic that consists of one layer of plastic and another layer of a different material, such as aluminium foil.

MLP is very hard to recycle at scale which means it can only be disposed of using methods such as incineration, which leads to carbon emissions or, by using it in road construction or cement kilns. MLPs are also extremely hard to collect and even if a ragpicker collects them, they fetch very little value.

Every year, groups of volunteers conduct brand audits in various countries as part of the ‘Break Free From Plastic’ movement. A brand audit involves counting and documenting the brands found on plastic waste to identify the companies responsible for plastic pollution. In 2021, more than 1,000 volunteers in 19 states across India conducted a brand audit involving 149,985 pieces of plastic, of which 70% were labelled with names of consumer brands.

The top three international companies polluting India with plastic, according to this report, are Unilever, Pepsico and Coca Cola. The top three Indian brands found in plastic waste were Parle, ITC Limited and Britannia. IndiaSpend reached out to all of them with queries on their EPR registration, total volume of plastic used, their EPR targets, percentage of MLP in total packaging and whether they have invested in research on alternatives.

In response, ITC Limited shared that it has gone past plastic neutrality (recycling as much plastic as it manufactured) in 2021-22. It collected and sustainably managed more than 54,000 tons of plastic waste across 35 states and Union Territories in India. “ITC will endeavour to ensure that 100% of its packaging is reusable, recyclable, compostable or biodegradable over the next decade,” a company spokesperson said over email, adding that the company has developed sustainable packaging solutions to substitute single-use plastics.

In response to our queries, Pepsico stated that it aims to design 100% of its packaging to be recyclable, compostable or biodegradable by 2025, increase recycled content in its plastics packaging to 50% by 2030, reduce 50% of virgin plastic per serving across its food and beverage portfolio by 2030 and invest to increase recycling rates in key markets by 2025.

“We have an EPR registration from CPCB, basis our action plan submitted to the regulatory authority, and we are on track to achieving our targets, like we have for the past few years,” stated a Pepsico spokesperson in an email response. “For the past two years, we have been achieving 100% equivalent of MLP collection and sustainable disposal in partnership with waste management partners across states. PepsiCo India has also been filing the annual returns as required under the Plastic Waste Management Rules. We are not using any of the single use items mentioned by the Government of India in the banned list, in our portfolio,” he added further.

While India does not have data on MLPs as a percentage of total plastic waste, the brand audit report said, based on its findings, “multi-layered plastics made up 35% of all plastic waste, and 40% of all branded plastic waste”.

You produce, you recycle

The EPR rules have mandated category-wise annual EPR targets for PIBOs starting last year (2021-22) and they are then supposed to use this recycled plastic into packaging from 2024-25 onwards. CPCB is authorised to levy environmental penalties on PIBOs who do not achieve their EPR targets and the violator will still have to meet their EPR goal the next year. The rules require PIBOs to provide an action plan containing their EPR target including average weight of plastic manufactured/imported/purchased.

“The rules mandated an action plan to be submitted by each of the brand owners by early 2017. There has been no update on this ever since and we are still oblivious to the amount and type of plastic waste we are generating and managing each year,” stated the Centre for Science and Environment’s Plastic Recycling Decoded report released in 2021. The report had listed unwillingness of the brands to publicly disclose their plastic usage and wide-spread collusion between the industry, recyclers and prescribed authorities as possible reasons behind this.

In a notification in July 2022, even the obligation on PIBOs to submit an action plan was removed, but they still have to disclose the volume of plastic they manufacture and their EPR targets. For example, if a producer is producing 100 metric tonnes of plastic in a given year, they have to disclose the same and if the target is to collect and dispose 25% of this in the first year, then their EPR target stands at 25 metric tonnes.

Few PIBO registrations

Forget the next steps, brands have lagged on the very first one–that is, registration. Under the new rules, PIBOs and plastic waste processors are not allowed to carry on any business without registration on the CPCB’s EPR portal.

There are 4,953 registered units engaged with plastic in 30 States/Union territories in India, the CPCB’s report from 2019-20 shows. This includes 3,715 plastic manufacturers or producers, 896 recyclers, 47 manufacturers of compostable plastic and 295 manufacturing MLPs.

“In India, we don’t even have an inventory of PIBOs. How will you check EPR compliance when you have a numerator [number of PIBOs registered] but no denominator [total number of PIBOs]?” asked Atin Biswas, Program Director (municipal solid waste) at CSE. The CPCB report pegs the number of unregistered plastic manufacturing/recycling units at 823 in nine states/UTs. The CPCB does not have public data on importers or brand owners in India. IndiaSpend reached out to the CPCB and the Union environment ministry regarding the total number of PIBOs in India. We will update the story when they respond.

So far, the CPCB’s online portal for registration of PIBOs has registered 662 brand owners, nine producers and 559 importers of categorised plastics, as of data from the portal’s homepage on October 11, 2022. The live dashboard on the portal says 772 brand owners, 822 producers, 1163 importers and 1,128 plastic waste processors have registered so far. We have asked CPCB why the numbers vary and will update the story when we receive a response.

Despite the EPR notification coming in as far back as 2018, why have all PIBOs not registered for EPR, especially when the rules prohibit them from doing any business without this mandatory registration? One reason, at least for small recycling units, could be the tedious process, as the rules have placed the burden of compliance specifically on them, explained Hiten Bheda, ex-President of the All India Plastic Manufacturers Association (AIPMA) and chairman of its environment committee.

“When it comes to recyclers, there are around 70 clusters comprising mostly informal units around India. Unfortunately, their efforts to formalise through registration are hampered by demand for back-dated fees, penalties and interest charges. The cost of complying with these amounts to lakhs which is beyond their financial capacity even before they can register themselves,” said Bheda. “These historical charges will have to be waived and you will have to do hand holding of small recyclers in order to get them to register.”

Multi-layered problem

Even if all PIBOs and waste processors undertake registration as mandated by CPCB, disclose their obligations and recycle a certain quantity of plastic, will India’s EPR rules actually reduce plastic waste that is ending up in landfills and oceans? Will the plastic be disposed of in an environmentally-conscious way?

In 2018, the government amended the original Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016 which had called for phasing out the manufacture and use of non-recyclable multilayered plastic in two years’ time. In the amendment, the phrase “non-recyclable multi-layered plastic” was substituted with “multi-layered plastic which is non-recyclable or non-energy recoverable or with no alternate use”.

“This gave producers a loophole to claim that packaging material, if not recycled, can be put to some other use [such as waste to energy],” noted the CSE’s Managing Plastic Waste report released in 2020. As incineration of plastic leads to carbon emissions, use of plastic in converting waste to energy, waste to oil or in cement kilns should not be a substitute for recycling and these options should only be considered when recycling is not possible, experts have pointed out.

There are also concerns of scope of corruption in the new regime.

“As part of EPR rules, every brand has to collect a recycling certificate from its recycling partner. The government has no way of finding out if that volume of plastic was actually recycled…Also, since EPR plan is purely based on voluntary disclosure, the government also cannot check how much plastic has been released into the market by these companies,” said Biswas, the programme director at CSE.

The rules have empowered pollution control boards to undertake periodic audits and inspections to check compliance of PIBOs and waste processors, but without an inventory of the total number of PIBOs, there are questions of what fraction of total plastic waste the EPR targets represent. It is only now, through the disclosures on the portal, that the authorities are hoping to gauge the plastic packaging material introduced in the market by PIBOs.

The CPCB is also expected to carry out a compositional survey of collected mixed municipal waste to determine the share of plastic waste, as well as of the different categories of plastic packaging material on a half-yearly basis, as per the EPR guidelines. IndiaSpend reached out to the CPCB and the Union environment ministry regarding the survey. This story will be updated when they respond.

“Behaviour of using plastic is supply-driven,” pointed out Swati Sheshadri, team lead at the Centre for Financial Accountability, a Delhi-based research organisation which tracks the role of financial institutions. “We were not used to buying sachets or pouches some decades ago, it is the companies which started selling products in that form. The concept of purity was pushed by the industry. Plastic is a supply-driven industry, not a demand-driven one,” she said of India’s larger plastic problem over the decades.

Sheshadri believes that self-regulation will not work for large corporations and that they should be asked to invest in research for alternatives to plastic packaging.

This CSE report had gone a step further and demanded that since the only stakeholders benefiting from MLPs are the brand owners and producers, they should be asked to pay extra taxes on its production and on its use.

Recycling in the informal sector

Notably, plastics are recycled at least five to eight times in India and almost all types of plastics are channelised and pre-processed by the informal sector before being passed to the formal sector to make finished plastic products.

Considering the contribution of the informal sector, the Break Free From Plastic-India report had noted that “there is a real danger that EPR will channel materials away from the informal sector and into a new, private sector, destroying the livelihoods of millions”.

The India report was authored by Lubna Anantakrishnan of Kashtakari Panchayat, a Pune-based NGO that supports waste pickers, their families and their collectives. Another NGO Swachh, a Pune-based co-operative society owned by waste pickers which is also part of BFFP network, under an EPR model collected over 1,800 metric tonnes of multi-layered plastics and diverted them away from landfills and cement plants with support from ITC Limited, a private business conglomerate that has many businesses, including consumer goods and packaging, and in association with the Pune Municipal Corporation. This initiative has contributed to a direct increase in income for waste pickers and emissions reduction of over 1,030 tonnes of CO2 equivalent, Swachh claims.

“Despite the efficiency and resilience of informal waste pickers and the recycling sector, non-recyclable plastics will continue to pose a serious environmental threat unless producers commit to eliminating them,” the Break Free From Plastic-India report had noted. “The current plastic packaging and delivery system only appears cheaper to companies because they have been able to externalise a major part of the life cycle costs of their products. It is time for these companies to internalise the true cost of their production and invest in sustainable systems.”

(Published in an arrangement with IndiaSpend.)