Climate change impact on winter: Winter is changing, and India is beginning to notice. The signals are no longer confined to melting glaciers or distant polar data. December cold spells in North India now arrive erratically. Himalayan snowfall fluctuates sharply from year to year. Southern India experiences unseasonal winter rain. According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the country has seen a steady rise in winter minimum temperatures over the past five decades, with sharper warming across the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayan foothills.

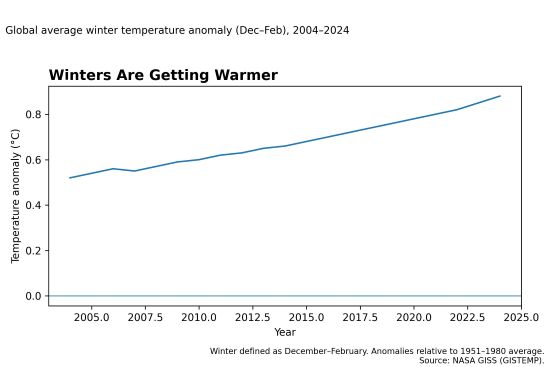

Globally, 2024 was the warmest year on record, and the first in which average temperatures exceeded 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, according to the World Meteorological Organisation. Winter has not disappeared. But its duration, intensity, and behaviour are changing in ways that carry serious economic and policy consequences.

READ I Climate change threatens India’s farm income goals

Warmer winters producing \extremes

Averages conceal risk. Extremes create damage. Climate science has long established that a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. This principle explains why rising temperatures do not eliminate winter precipitation, but intensify it. Across Europe, winter storms now deliver heavier rain and snow, overwhelming drainage systems designed for milder variability. In East Asia, warmer winters have increased the frequency of freeze-thaw cycles, accelerating damage to roads and rail networks.

India is not insulated. Studies by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology show rising winter humidity over northern and eastern India, increasing the likelihood of intense rainfall events during traditionally dry months. In the western Himalayas, warmer winters have produced erratic snowfall — lighter overall accumulation, punctuated by sudden heavy snowstorms. These swings destabilise slopes and raise avalanche risks. Winter is no longer steady. It oscillates.

READ I Climate diplomacy must account for domestic inequalities

Shorter winter and water security

What is shrinking globally is not winter precipitation, but winter duration. Across the Hindu Kush–Himalayan region, winter snowpack is declining and melting earlier. According to the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), glaciers feeding the Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra basins are losing mass at accelerating rates. Snow that once accumulated gradually through winter now melts earlier, reducing spring and summer water availability.

This shift matters deeply for India. Snowpack functions as delayed storage. Rain does not. Earlier melt increases winter runoff but weakens river flows during peak irrigation months. The result is a familiar paradox: floods in winter and early spring, water stress in summer. The World Bank has warned that climate-driven hydrological volatility could reduce India’s agricultural productivity unless basin-level water planning adapts quickly.

Similar patterns are visible elsewhere as climate change sets in. In Central Asia, shorter winters have weakened snow-fed agriculture. In Southern Europe, rain-heavy winters now increase erosion without replenishing groundwater. The problem is systemic, not regional.

READ I Climate change turns farms into migration corridors

Agriculture losing seasonal certainty

Agriculture depends on predictable cold periods. That predictability is eroding. Warmer winters allow pests and pathogens to survive across seasons. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has documented rising winter pest survival in temperate and subtropical regions, increasing crop losses and pesticide dependence. In India, horticultural crops that require winter “chill hours”, including apples and stone fruits in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, are already showing declining yields and geographic retreat to higher altitudes.

Shortened winters also compress planting calendars. Crops face heat stress earlier in their growth cycle. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that such seasonal shifts disproportionately affect small farmers, who lack irrigation buffers and crop insurance. Winter’s erosion is quietly reshaping rural risk.

Infrastructure and climate change impact

Most infrastructure assumes stable seasons. That assumption is now obsolete. In Europe, winter flooding has become a major source of economic loss as rainfall replaces snowfall. In Japan and South Korea, repeated freeze-thaw cycles have increased maintenance costs for transport networks. India faces a different but related risk. Urban drainage systems, already stressed, are ill-equipped to handle intense winter rainfall events. Hill states face rising landslide risk as unstable winter precipitation weakens soil cohesion.

The World Bank and Asian Development Bank have both warned that South Asia’s infrastructure deficit is not merely one of quantity, but of climate change suitability. Roads, bridges, and power systems built for twentieth-century winters are failing under twenty-first-century variability. Disaster response remains reactive. Adaptation investment remains inadequate.

Health and ecology are absorbing shock

Seasonal change affects biology before policy. When winters shorten, ecosystems lose timing cues. Pollinators emerge earlier. Plants bloom sooner. Migratory patterns shift. According to the IPCC, these phenological mismatches are increasing ecosystem instability across latitudes. In India, altered winter temperatures have been linked to changes in bird migration and forest flowering cycles.

Human health risks follow. Warmer winters can worsen air pollution by trapping particulates close to the surface, especially in northern Indian cities. The World Health Organisation has linked changing seasonal patterns to higher respiratory and cardiovascular risks. Vector-borne diseases are expanding their geographic range as colder months lose their protective effect.

These burdens fall unevenly. Low-income communities face greater exposure to flooding, pollution, and energy insecurity. Climate change does not just alter seasons. It magnifies inequality.

Climate change and winter policy

Climate policy remains biased toward summer extremes. Heatwaves and droughts dominate planning. Winter risk is treated as manageable. That belief is increasingly costly.

Adaptation strategies must recognise that seasons themselves are changing. Building codes need revision for heavier winter rainfall and snow loads. Water policy must protect snow-dependent basins. Agricultural insurance must reflect shifting frost and pest risks. Urban planning must prepare for winter flooding, not just monsoon deluge.

The World Bank estimates that every dollar invested in climate change-resilient infrastructure avoids up to four dollars in future losses. Yet globally, adaptation spending continues to trail mitigation by a wide margin. That imbalance will not remain abstract. It will surface in farm incomes, municipal finances, and insurance losses.

Winter still arrives each year. It simply no longer behaves as it once did. Policy that assumes otherwise is planning for a climate that no longer exists.