There is a moment in every policy debate when facts cease to shock and start to numb. That moment may have arrived with the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, a vast conveyor belt of warm and cold waters that shapes global weather, stabilises sea levels, and keeps entire ecosystems in balance. Scientists have long warned of its weakening. New research confirms that it is already altering flood patterns on the US Northeast coast, hastening sea level rise, and may be on course to collapse — not in the distant future, but possibly by mid-century.

This is not the script of a Hollywood disaster movie. It is the sober judgment of some of the world’s most respected oceanographers and climatologists. And yet, governments remain distracted by fossil fuel lobbies, climate diplomacy posturing, and denial cloaked as “economic pragmatism.” The planet, meanwhile, may be shifting beneath our feet — or more precisely, under our waves.

READ I US-China trade truce can buy time, not trust

The AMOC: Earth’s climate circulatory system

The AMOC is no ordinary current. It is the cardiovascular system of the planet, moving warm surface water from the tropics to the North Atlantic, where it cools, sinks, and returns southward along the ocean floor. This engine distributes heat, drives the Gulf Stream, stabilises sea levels, and moderates winter temperatures in Europe.

But the engine is faltering. Greenland’s glaciers are melting at record rates, pouring cold, fresh water into the North Atlantic and diluting the salty water necessary for the AMOC to function. As the waters lose density, they no longer sink, disrupting the entire circulation.

The consequences are alarming. A recent study published in Science found that up to 50% of flooding events along the northeastern US coast from 2005 to 2022 were linked to a weakening AMOC. This translates into eight additional flood days a year — not due to rainfall or storm surge, but because the very geometry of the ocean is changing.

Atlantic warming hole and the cooling paradox

If the planet is warming, why is there a growing patch of cold water southeast of Greenland? That anomaly — dubbed the “warming hole” — has puzzled scientists for years. We now know it is not a quirk of atmospheric dynamics, but a direct symptom of the AMOC’s decline. As heat fails to reach the North Atlantic, waters cool disproportionately, destabilising the energy balance of the planet.

The cooling in the North Atlantic does not mean global warming is reversing. Quite the opposite. It may produce unexpected, and in some cases, perverse consequences: frigid winters in Europe, sea level surges along the US eastern seaboard, disrupted monsoons in South Asia, and even prolonged droughts near the equator as the Intertropical Convergence Zone shifts southward. The destabilisation is not regional; it is planetary.

A sea-level crisis accelerated

Since 1993, global sea levels have risen by more than 4 inches. NASA satellites confirm that the rate of sea level rise has doubled in the last three decades. By 2050, we may see an additional 10–12 inches along US coastlines — and more if the AMOC weakens faster than expected.

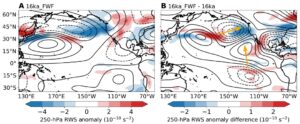

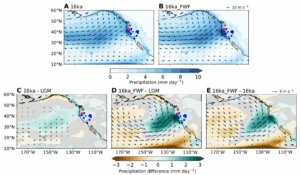

Winter precipitation, winds and anomalies

The danger is not limited to inundated coastlines. High-tide flooding is now two to three times more frequent along the US Atlantic and Gulf coasts than in the 1990s. These are “sunny day floods,” occurring without storms, driven by nothing more than rising baseline ocean levels. If the AMOC’s influence continues to expand, even small perturbations in sea level could devastate infrastructure, overwhelm drainage systems, and compromise freshwater aquifers — as already witnessed in Pacific Island nations and Louisiana.

The myth of gradualism

Climate change used to be sold to the public as a slow-moving problem with time for measured responses. The AMOC tells a different story. It can change quickly — as it has in the past. Paleo-climate records suggest the AMOC has collapsed before, bringing abrupt shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns.

Today, we are perilously close to replicating such a collapse. Scientists disagree on when the tipping point will arrive — some say it could be as early as 2050, others caution that uncertainty in past data makes precise predictions impossible. But all agree: we are approaching it. And the window for pre-emptive action is closing.

The price of uncertainty is inaction

Even with the growing mountain of evidence, political will remains stagnant. Former US President Trump’s climate rollbacks — including the gutting of Earth science budgets and withdrawal from the Paris Accord — came at a time when the oceans demanded more attention, not less. While scientists race to refine their models, politicians dither over commitments and concessions. The result? A world where adaptation may soon replace prevention.

Let us be clear: even in the best-case scenario — a 10% decline in AMOC strength — there will be noticeable impacts: colder winters in Europe, disrupted agriculture, more volatile weather. At 50%, the consequences become severe. And while a total collapse may be unlikely, it is not impossible — and need not occur for global systems to unravel.

Ethics, not forecasts, should drive climate policy

In a world governed by quarterly profits and election cycles, long-term planetary risk is treated as speculative fiction. But the AMOC does not care for our political timetables. It is governed by physics, not public opinion.

What is at stake is not just climate predictability, but intergenerational justice. Today’s emissions may not flood New York or parch West Africa — but tomorrow’s children will live with the consequences. As Dirk Notz of the University of Hamburg rightly said, “The catastrophe will come further down the road when those who have caused the problem are no longer around.”

The moral imperative to act now

The case for urgent action is overwhelming. We need massive, rapid cuts in carbon emissions, large-scale investments in ocean monitoring and early-warning systems, and international agreements that prioritise climate adaptation.

The weakening of the AMOC is not a footnote in the climate story. It is the headline. It may not come with sirens or spectacle, but it is already reshaping the physical world. And unless we respond with urgency and unity, it may soon reshape our political and economic futures.

The lesson of the AMOC is simple but chilling: we are not just warming the planet — we are altering its fundamental circulatory system. And we are doing so without maps, without brakes, and without a plan.

If the world’s policymakers will not act out of prudence, let them act out of fear. Fear of sea levels that rewrite coastlines. Fear of rainfall that abandons fields. Fear of the chair that tips, not gradually, but suddenly and irreversibly.

The science is uncertain, yes. But the stakes could not be clearer.