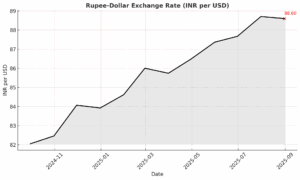

Every gain of the rupee against the dollar eases India’s import bill and strengthens household purchasing power. Conversely, a weaker rupee inflates costs across the economy, from fuel to foreign education. Over the past decade, the Indian currency has lost about 30.6% of its value against the dollar. More recently, it slipped to a record low of 88.76 before rebounding modestly to 88.70, aided by a softer greenback and cautious optimism on India–US trade negotiations. Yet most analysts warn that any recovery will be patchy, as structural headwinds persist.

The rupee’s weakness has unfolded against a broader backdrop of volatile currency markets. The dollar, buoyed by elevated Treasury yields and a flight to safety, has appreciated against most emerging market currencies. The Japanese yen has slipped to multi-decade lows, forcing Tokyo to consider intervention. The Chinese yuan, pressured by sluggish growth and capital flight, has struggled to hold ground despite state support. Even the euro has been under strain from uneven growth within the bloc.

By contrast, commodity-linked currencies like the Brazilian real and the Russian rouble have seen support from high energy and raw material prices. In this global context, the rupee’s fall is not unique, but its dependence on imported oil and external capital flows makes its position more precarious.

READ I India’s inflation outlook under pressure from global trends

External pressures mount on rupee

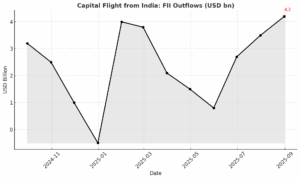

Foreign institutional investors (FIIs) have turned net sellers, offloading equities worth nearly ₹5,000 crore in a single session this month. These outflows raise dollar demand and weaken the rupee further. The trend is aggravated by strong importer demand for dollars and subdued remittance inflows from exporters.

Adding to the strain is a rebound in crude oil. Brent prices have climbed back to nearly $70 a barrel, widening India’s import bill and raising the current account deficit. For an economy that imports over 85% of its crude needs, this is a decisive blow.

The external environment is no less punishing. The re-imposition of steep US tariffs—50% on select Indian exports—has rattled markets. The surprise hike in H-1B visa fees has also clouded the earnings outlook of India’s IT sector, one of the few services industries that brings in steady dollar inflows. Together, these measures weigh on investor confidence and worsen the rupee’s trajectory.

Real effective exchange rate

While the nominal rupee is sliding, its real effective exchange rate (REER)—a trade-weighted index adjusted for inflation differentials—suggests undervaluation. RBI data shows REER fell to 98.79 in July from 100.36 a month earlier, its weakest level since February 2019. Since India’s inflation is lower than that of several trading partners, the rupee remains more competitive in real terms.

This offers some respite for exporters, particularly in labour-intensive sectors like textiles and gems, who gain from a cheaper currency. The RBI is thought to prefer keeping REER between 96 and 104, allowing enough room to balance competitiveness with stability. Yet, persistent import inflation—especially from energy and gold—threatens to erode this advantage.

RBI’s balancing act

The Reserve Bank has historically intervened to smooth sharp volatility rather than defend a fixed level. Market participants say the rupee’s fall would have been far steeper without RBI action in recent weeks. Still, the central bank appears comfortable allowing gradual depreciation, as long as it does not turn disorderly.

All eyes are now on the monetary policy review scheduled for October 1. A Reuters poll suggests the RBI will hold the repo rate at 5.50%. Its twin challenge remains unchanged: to support growth while containing inflation. The rupee’s fate will hinge not only on domestic policy but also on global risk appetite, the trajectory of US interest rates, and progress in trade talks with Washington.

Rupee outlook for 2025

Most forecasts expect the domestic currency to end the year in the 88–90 range, though some pessimists warn of a slide past the psychological barrier of 90 if capital outflows intensify or US rates remain elevated. On the technical charts, analysts point to resistance near 89.00–89.20 and support around 88.40. A breach below support could trigger sharper depreciation, while easing tariffs or fresh inflows may enable a modest rebound.

The risks are clear: higher crude oil prices, worsening trade disputes, and renewed global risk aversion could drag the rupee lower. Yet, there are silver linings. India’s potential inclusion in global bond indices could unlock billions in passive inflows. A revival in FDI and export growth, backed by macroeconomic discipline, may stabilise the currency.

For now, modest depreciation remains the base case. The local currency may hold its ground if policymakers can ease external pressures through trade diplomacy and sustain investor confidence. Otherwise, the slide past 90 looks less like a possibility and more like a probability.