Massive NPA write-offs: Non-performing assets to the tune of Rs 10 lakh crore were written off in the five years between 2016-17 and 2021-22 while the banks managed to recover only Rs 1.32 lakh crore or only about 13% of the written off loans, the RBI said in response to an RTI query. The recent fall in the NPA numbers could largely be attributed to these write offs. The gross NPA rate fell to 5.9% in March 2022 from a peak of 11.2% in March 2018, according to RBI data. The massive write-off is equivalent to 61% of the country’s gross fiscal deficit of Rs 16.61 lakh crore in 2022-23, suggesting that all is not well with our banking system and its NPA resolution mechanism.

The banks and the RBI do not disclose the names of major defaulters. State Bank of India has reduced the NPAs by Rs 2,04,486 crore in the last five years. For Punjab National Bank, the figure is Rs 67,214 crore, and for Bank of Baroda Rs 66,711 crore. Among private banks NPAs of ICICI Bank fell by Rs 50,514 crore after write-offs. It is a regular practice for banks to write off bad loans to make their books look good. While the loans are taken off from the books, the banks reserve the right to recover the amount from defaulters.

READ I RBI paper busts the myth of inefficient PSU bank

The lessons from NPA write-offs

The massive write-offs raise the issue of distribution or allocation of financial resources as the written off loans of public sector banks which amounts to Rs 7.35 lakh crore is public money. The above event underscores the following concerns with respect to the manner in which the NPA issue was handled and the NPA resolution process.

- The massive write-off leading to a decline in NPAs paints a misleading scenario. RBI data shows that the gross NPAs stood at Rs 10,39,679 crore in March 2018 and declined to Rs 9,33,609 crore in March 2019. The NPAs fell by Rs 1,06,070 crore and the written off loans in 2017-18 was of Rs 1,61,328 crore. In subsequent years, the amount of written off loans exceeded fall in NPA figures. Data suggest that the decline in NPA figures is due to these write offs, but also written off loans tend to exceed the fall in NPA figures. This clearly suggests that the remedial policy measures or interventions have not been so effective.

- The numbers negate the widely perceived notion that all is well with the private banks and they are inherently efficient. The private banks have written off Rs 2 lakh crore worth bad loans. Over decades, the PSBs have been unfairly targeted despite the fact that in the post liberalisation period, the responsibility of lending to large industrial projects with long gestation period fell on them while private banks are not under any such obligation. They tend to refrain from lending to large industrial projects. Nevertheless, these banks accumulated NPAs to the tune of Rs 2lakh crore.

- The fact that the banks could recover only 13% of the total written off loans during last five years suggests that the NPA resolution mechanism is either working inefficiently or failed miserably. Hence, there is a need to redesign the mechanism. In the post-IBC period, it was expected that the recovery rate would increase significantly. However, data suggests that the recovery proceeds are relatively low in comparison to the claims of financial creditors. Realisation value as percentage of admitted claims can be as low as 2%. The overall realisation as percentage of admitted claims stood at 30.79% as of September 2022.

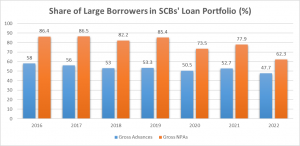

- The written off loans raise the issue of distribution and allocation of financial resources in our economy. On an average, more than half of bank credit has gone to large borrowers and the incidence of loan default or NPA is quite high among this borrower category. Between 2018 and 2022, the average share of large borrowers in banks’ loan portfolio stood at 51.5% and their average share in NPAs of banks was 76.3%. With these write-offs, these defaulted loans are now shown as loss in banks’ balance sheets. With low recovery rate, significant amount of public money is lost on account of the misdeeds or misuse of public money by the large borrowers.

- The large NPA write-offs do not receive as much public attention as welfare schemes and subsidies. In the recent past, welfare schemes and subsidies that are largely targeted to the poor and vulnerable sections of the society have been termed as freebees. Except in the pandemic years, the average expenditure on food and fertiliser subsidies was less than Rs 2 lakh crore.

- The huge write-offs will have an adverse macroeconomic impact in terms of economic expansion. Banks provide for write-offs from their profit to clean their balance sheets. Alternative use of the profit deployed for write-off could have contributed to much needed credit expansion for output growth. In this perspective, Rs 10 lakh crore could have contributed to the expansion of the economy.

- Given that more than half of the bank credit goes to large borrowers, mostly to the corporate sector, and when more than three fourth of the borrowed funds have turned into NPAs, it raises the question whether Indian corporates minimise their own risk capital by way of shifting it to PSBs. Unlike in advanced economies, they look for external sources of funds for expansion and growth. As internal fund is not at stake, corporates tend to take either excessive risk with borrowed money or to misuse the borrowed fund as reflected in the wilful default data.

- Finally, the question arises: where does the defaulted fund go? Does it go one way or another to enlarge corporates’ kitty without corresponding contribution to the economy? If that happens, it worsens the already skewed income and wealth patterns. The larger issue is how to move out of crony capitalism at one level and banks’ ineptitude at the other.

(Santosh Kumar Das is a researcher with the Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, New Delhi. Atul Sarma is a Delhi based economist. He was a member 13th Finance Commission and a former Vice Chancellor of Rajiv Gandhi University.)