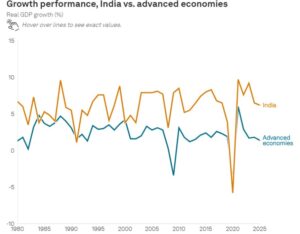

India’s economic growth: India remains the world’s fastest-growing major economy — a bright exception in an otherwise subdued global landscape marked by protectionism, slowing trade, and geopolitical uncertainty. Despite the 50% tariff imposed by the United States on Indian exports, the economy has continued to display surprising resilience. The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook places India’s FY2025–26 growth at about 6.6%, while Crisil and S&P Global maintain similar forecasts of 6.5%. This confidence is rooted in the momentum of a strong first quarter and sustained domestic demand, both of which have offset the drag from a weakening external environment.

A mix of favourable domestic conditions has supported this growth — good rainfall, easing oil prices, and moderating inflation have combined to keep consumption buoyant. The Reserve Bank of India’s cautious monetary stance and the government’s continued emphasis on capital expenditure have further strengthened this momentum. Yet, the question lingers: can a growth model powered largely by domestic consumption and public spending hold up if global demand falters further?

READ | RBI must wait on rate cuts despite falling inflation

Uneven growth and K-shaped reality

Behind the impressive growth figures lies a disquieting truth — India’s recovery is uneven and fragmented. The benefits of growth are concentrated at the top, while much of the informal economy struggles to regain its footing. Economists describe this divergence as a K-shaped recovery: the upper arm represents the formal sector and affluent households that continue to spend on high-value goods such as automobiles, real estate, and air travel; the lower arm reflects the stagnation in rural incomes and low-end manufacturing.

The 50% US tariffs have deepened this divide. Labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, leather, gems and jewellery, and seafood — mainstays of export employment — are bearing the brunt of reduced competitiveness. These industries are dominated by micro and small enterprises that lack the financial resilience to withstand external shocks. As export orders weaken, job losses in these segments are likely to rise. The outcome is an economy where the formal sector thrives even as the informal sector, which employs the majority of workers, faces erosion. The risk is that such an imbalanced growth pattern will undermine the broad-based consumption base necessary for long-term stability.

Structural fragilities: Labour, land, investment

The foundations of India’s economy remain weakened by unresolved structural problems. Labour market rigidities continue to hinder large-scale formal job creation. Land acquisition remains cumbersome and politically fraught, discouraging private investment in manufacturing. Despite a surge in public infrastructure spending, private corporate investment has remained tepid, constrained by policy uncertainty and weak global demand.

Both the IMF and the World Bank have sounded caution, projecting growth to moderate to around 6.2% by FY2026–27. Their warnings reveal the fragility beneath the surface. Public capital expenditure has kept investment activity afloat, but without renewed private participation, India risks plateauing before reaching its potential. To achieve the ambitious target of becoming a developed economy by 2047, the country will need to go beyond government-led spending. Land and labour reforms, alongside efforts to simplify logistics and regulation, must become the centrepiece of the next phase of economic strategy.

External shocks and trade dependence

Although India’s economy is driven primarily by domestic demand, its exposure to global forces has increased substantially. Exports now make up more than a fifth of GDP, while financial flows account for nearly a third. This growing openness means that trade disruptions, capital volatility, and slower demand in key markets can quickly ripple through the domestic economy.

The United States, India’s largest export destination, is expected to slow to 1.7% growth in 2025, from 2.8% in 2024—a development that will hurt Indian exports. Europe, which accounts for another 17% of India’s trade, remains sluggish. Meanwhile, China’s industrial overcapacity and soft domestic demand could lead to dumping of low-cost goods in global markets, including India, threatening local manufacturers. Though safeguard duties can provide temporary protection, long-term competitiveness will depend on improved productivity and deeper integration into global supply chains. A timely conclusion of the pending India–US trade agreement will be critical to maintaining export momentum and securing better access to Western markets.

Inflation, oil, and policy levers

For now, domestic fundamentals remain favourable. A good monsoon has lifted agricultural output, helping contain food inflation and support rural purchasing power. Crude oil prices, projected to average between $65 and $70 a barrel in FY2026 compared to nearly $79 last year, have helped lower import costs and ease the current account deficit, which remains around 1% of GDP. India’s foreign exchange reserves, at over $700 billion, are among the world’s strongest cushions against external volatility.

Inflation has also eased to within the Reserve Bank’s 4% target band, allowing the central bank space for another policy rate cut. Combined with income tax relief and the proposed rationalisation of the goods and services tax, these measures should bolster urban consumption in the coming quarters. Yet, fiscal space is tightening. The Centre aims to reduce its fiscal deficit from 4.8% in FY2025 to 4.4% in FY2026, leaving limited room for additional spending. With borrowing constrained, the government must now prioritise the efficiency of expenditure—particularly in infrastructure and welfare—rather than its expansion.

The road to 2047: Balancing growth and inclusion

Sustaining high growth over the next two decades will require India to address both its structural and cyclical weaknesses. The services sector, which now accounts for nearly half of India’s total exports, provides resilience against global trade volatility, but overreliance on it will not suffice. A vibrant manufacturing base, competitive exports, and high-quality job creation must form the next layer of the growth story.

To get there, India needs a recalibration of economic priorities. Land and labour laws must evolve to attract long-term investment. Trade diversification is essential to mitigate risks from concentrated export markets. Regulatory simplification and stable tax policies can reduce business uncertainty and improve investor confidence. Equally important, the government must strengthen support for micro, small, and medium enterprises, helping them scale up and integrate into global value chains.

India’s resilience is commendable, but resilience is not invincibility. As the world enters an era of fracturing supply chains, shifting alliances, and slower trade, India’s economic success will depend on how deftly it adapts to this volatility. The strong numbers on paper are a testament to domestic strength; sustaining them will require the political will to build a more balanced, inclusive, and outward-looking economy. The applause for today’s growth should not obscure the harder task ahead—laying the foundations for tomorrow’s prosperity.