The government presented the Economic Survey 2025-26 in Parliament, reviewing India’s economy and setting up the macroeconomic outlook ahead of the Union Budget 2026-27. Other than the usual growth projections, the survey carried a significant subtext. While markets have quietly been pricing in for some time, policymakers are only now beginning to confront that beyond the comforting indicators of GDP growth, inflation trajectory and external sector resilience, the fiscal behaviour of India’s states carry significant risks for borrowing costs and the broader macroeconomic balance. This is an uncharted terrain in the history of Economic Surveys.

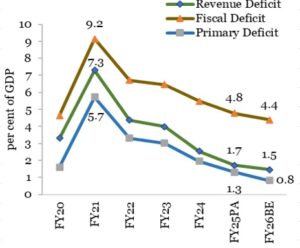

The government achieved a fiscal deficit of 4.8% of GDP in FY25, better than the budgeted 4.9%, and has committed to narrowing it to 4.4% in FY26. These figures suggest disciplined consolidation and a responsible approach ahead of the budget. However, wishing is one thing and hard numbers are another. General government finances of both the Centre and states are a better marker for market scrutiny.

READ I What Economic Survey 2025-26 reveals about India’s growth path

Debt markets watching state debt

India’s debt markets no longer look solely at the Union’s fiscal metrics. Instead, they have begun pricing in the latent risks emanating from state governments. Their borrowing programmes, deficit financing behaviour and the quality of their expenditure are in question. The evidence of this shift is visible in the sovereign yield curves themselves.

Despite sharing a BB B credit rating with Indonesia, India’s 10-year government bond yield hovers around 6.7%, notably above Indonesia’s approximately 6.3%. Traditional explanations such as inflation differentials or monetary policy stance do not fully account for this spread. The survey said that investors are charging India higher borrowing costs because they are worried about how much state governments are borrowing and spending and not just taking into account the Centre’s finances.

READ I Budget 2026 must shift focus from slogans to delivery

Economic Survey 2025-26 issues warning

What has brought this latent risk to the fore is an unprecedented state-level borrowing push. According to the Reserve Bank of India’s indicative calendar, states and union territories are preparing to raise nearly Rs 5 trillion from the market in the January-March quarter alone. This is a historical high. If fully realised, this would make the fourth quarter account for nearly two-fifths of annual state borrowings.

Such a clustering of supply matters in bond markets. The Economic Survey 2025-26 said that state borrowings are no longer passively absorbed in the secondary market. Investors and portfolio allocators increasingly evaluate general government borrowing pressures and the timing and concentration of state debt issuance itself becomes a driver of yield outcomes. This is a critical evolution in market behaviour. What was once a largely segmented and predictable stream of Development Loans issued by states has now become a feature in the pricing of India’s fixed-income assets.

READ I Budget 2026: Need ‘quality of solace’ proposals

Why are states borrowing this much?

On the expenditure side, states carry a much heavier weight of welfare and social spending than in the past. Running public distribution systems, direct cash transfers, health programmes, housing initiatives and other politically charged schemes have ballooned state budgets. These liabilities are sticky- salaries, pensions, interest payments and subsidies together take up nearly a third of states’ revenue expenditure. The state governments have been unable to cut even in times of fiscal stress.

However, while expenses are rising, states are not able to raise revenues. GST and tax devolution have stabilised some receipts, but states largely cannot set their own tax rates or significantly expand non-tax revenues. Borrowing increasingly fills that void.

The demand situation has changed as well. Earlier, big institutional investors like insurance companies and pension funds used to buy a large share of government and state bonds and hold them for the long term. Now, many of them are putting more money into shares and other investments that offer higher returns. As a result, they are less willing than before to buy long-term government bonds. This means states are trying to borrow more money at a time when their most dependable buyers are more cautious. When fewer big investors are ready to buy and the amount of bonds being issued is rising sharply, it puts extra pressure on the market.

The concentration of state issuance among a handful of large states viz Karnataka and Maharashtra tapping the market almost weekly, with others like Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh repeatedly borrowing substantial sums has magnified the risk. Markets are sensitive to fiscal discipline exhibited by individual states and periodic revenue deficits financed through market borrowings shift the composition of debt and weaken sustainability, even if aggregate headline deficit ratios remain seemingly stable.

The road ahead

Going ahead, policymakers need to look beyond just the government’s deficit targets and focus on the overall fiscal health of both the Union and the states, because markets judge India on this combined picture. The challenge is to maintain fiscal discipline without ignoring the financial pressures and political realities states face.

Rather than imposing only tight borrowing limits, the approach should encourage states to spend more on productive capital investment, improve the quality of their expenditure and get more flexibility in raising their own revenues so they are not funding routine costs through debt.

Reforms must also recognise that welfare schemes and cash transfers are politically and socially embedded, making abrupt cuts difficult. The Economic Survey 2025-26’s message is clear- India’s fiscal future depends on managing this complex centre-state balance carefully.