Budget 2022: Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented her fourth union budget on February 1, at a time when India is reeling under the third wave of Covid-19. The pandemic has posed many challenges to the fragile economic recovery. The Narendra Modi government’s tenth budget tried to address issues such as slack demand in the economy and rising unemployment by focusing on four pillars — inclusive development, productivity enhancement, energy transition and climate action.

“The budget gives a blueprint of the economy from India at 75 to India at 100,” she said in her Budget speech in the Lok Sabha. The United Nations World Urbanisation Prospects report says India will continue to be predominantly rural even after 100 years of independence. Rural India has around 140 million households whose purchasing behaviour is usually linked to farm output. Recognising this, efforts have been made to boost growth in agriculture and rural economy.

READ I Spectre of inflation comes back to haunt Indian economy

Budget 2022 in numbers

The size of the budget for the financial year 2022-23 is Rs 39.49 lakh crore, or around 18% of the GDP. This is Rs. 4.61 lakh crore more than the budget estimate (BE) in the last fiscal year. The government intends to spend 13% more in FY23 than what it has earmarked in FY22. The higher spending will support demand and help faster recovery. To boost investment, Rs 10.67 lakh crore (4.1% of GDP) has been kept for effective capital expenditure (Capex), which is an impressive increase of 38.03% over the budget estimate of FY 22.

Borrowing and other liabilities with a 35% share will constitute the largest chunk in the total estimated receipts for FY23, followed by 16% from GST and 15% each from income and corporate tax. In the total estimated expenditure, the highest 20% will go for interest payment followed by 17% for transfer in states’ share of taxes and duties, 15% for central schemes, 10% in other transfers to states, and 8% each for defence and subsidies.

The revenue receipts for FY23 have been estimated to be Rs 22.04 lakh crore which is Rs 1.26 lakh crore more than the revised estimates for FY22. Thus, the fiscal deficit-GDP ratio is estimated to be 6.4% for FY23 compared with the revised 6.9% for FY22. Thus, the statement of account of the government conveys a common message — more government expenditure. The Budget also sets a highly ambitious net tax revenue target of Rs 19.34 lakh crore which is 25.18% more than estimated net tax receipts for FY22.

READ I Centre, states must take green bonds route for clean energy, environment

Rural economy and agriculture

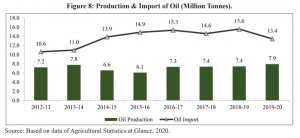

While recognising the need of the minimum support price, the FM announced a rationalised scheme to increase domestic oilseed production to cut down imports. India is the world’s second largest consumer of vegetable oil and the world’s largest importer. Its consumption is expected to remain high because of rapid population growth and urbanisation. OECD-FAO substantiates this in their Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030, stating that with a growth rate of 2.6% per year, India is expected to remain a high per capita vegetable oil consumption nation. By 2030, vegetable oil consumption of India will be 14 kg per capita which will necessitate a 3.4% increase in imports per year. Considering these facts, policy intervention for reducing edible oil imports is necessary.

The production of oilseeds in India has grown by 43% between 2015-16 and 2020-21. The country has a huge potential for oil palm development and production of crude palm oil. As per the Economic Survey 2021-22, oil palm agriculture covers only 3.7 lakh hectares at the moment. Compared with other oilseed crops, oil palm generates 10 to 46 times more oil per hectare and yields roughly 4 tonnes of oil per hectare. Despite this fact, about 98% of CPO is still imported in India today.

The National Mission on Edible Oils – Oil Palm (NMEO-OP) which was initiated in 2021 might be regarded as a major government endeavour. Until 2025-26, the project aims to cover an additional 6.5 lakh hectares of oil palm land, bringing the total to 10 lakh hectares. In addition, the project aims to increase CPO production to 11.2 lakh tonnes by 2025-26 and to 28 lakh tonnes by 2029-30.

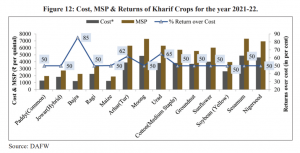

Considering the highest expected return (85%) over the cost of production in the case of millets, the year 2022-23 was declared as the International Year of Millets.

Recognising the rising trends of fragmented landholding and rise in the number of small farmers, Sitharaman announced a scheme of new products for small farmers and MSMEs. As per the Situation Assessment Survey (SAS) 2021, the average size of holdings has declined from 0.725 hectares in 2003 to 0.592 hectares in 2013 and further to 0.512 hectares in 2019. The share of small and marginal farmers has also increased from 80% in 2003 to 85% in 2013 and 86% in 2019. Therefore, the situation necessitates a greater focus on measures like the development of small farm technology, boosting non-farm businesses and development of allied activities including animal husbandry, dairying and fisheries.

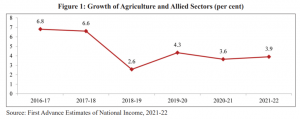

Allied sectors including animal husbandry, dairying and fishing, and investment in agriculture are areas that require further push and serious policy interventions for the prosperity of farmers and the rural economy.

As per the Economic Survey 2021-22, the allied sector has emerged as a high growth sector. According to the latest Situation Assessment Survey, the agricultural sector has remained a consistent source of income for farm households, accounting for around 15% of their average monthly income. This increase in allied sector contribution is in line with the Committee on Doubling Farmers’ Income’s (DFI 2018) recommendations which advised a stronger focus on allied sectors to improve farmers’ income.

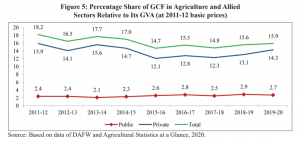

In the last 10 years, the Gross Capital Formation (GCF) in agriculture and associated sectors has been oscillating in relation to the sector’s GVA. This is because of wide fluctuations in private investment. Over the year, the public investment has remained stable between 2-3%. Considering that there is a direct relationship between capital investments in agriculture and the sectoral growth rate, a focused and targeted approach is needed to ensure increased public and private investment in the sector. Budget 2022 seems to have lost an opportunity in this particular area.

(Shashank Vikram Pratap Singh is Assistant Professor at Shri Ram College of Commerce, University of Delhi.)