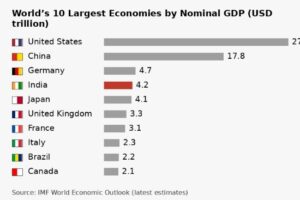

Indian economy: India has crossed a symbolic threshold. In nominal terms, it has overtaken Japan to become the world’s fourth-largest economy, with GDP estimated at about $4.18 trillion. Official projections suggest Germany could be next within 3 years. International agencies broadly concur. The International Monetary Fund expects India’s nominal output to cross $4.5 trillion by 2026. Rankings matter because they shape how countries are perceived and heard. But they also invite confusion.

For a nation of 1.4 billion people, moving up the GDP table does not automatically translate into economic power. That transition depends on jobs, productivity, institutions, and credibility. On those measures, India’s development model still shows unresolved strains.

READ | Why the GDP growth data feels disconnected from the real economy

Rank does not raise incomes

India’s climb up the global league table reflects genuine momentum. Nominal GDP has doubled since 2014, supported by strong domestic demand and favourable demographics. Yet aggregate size conceals living standards. Per-capita income remains near $3,000, far below China’s and a fraction of advanced economies. The World Bank continues to classify India as a lower-middle-income country, and state-level disparities remain stark.

Recent growth has leaned heavily on consumption, particularly urban consumption. Credit growth and post-pandemic pent-up demand have sustained expansion. That has kept topline numbers buoyant, but it has done less to lift household incomes broadly. Rural wage growth has been patchy. Female labour participation has improved, but unevenly across regions. The gap between national output and household earnings is where India’s growth narrative begins to thin.

Indian economy: Jobs remain the weakest link

Economic power rests on employment that is both abundant and productive. Here, India’s record remains mixed. Output has expanded faster than job creation, especially in manufacturing. Despite repeated policy emphasis, manufacturing’s share of GDP has stayed stubbornly in the mid-teens for over a decade.

Services absorb labour, but often at low productivity levels. Recent labour force surveys suggest unemployment has moderated since the pandemic shock, but job quality remains the larger concern. Informality continues to dominate. Social security coverage is limited. The four labour codes, enacted after 2019, remain unevenly implemented across states. Without a sustained push towards labour-intensive manufacturing and export-oriented services, growth will struggle to translate into durable employment gains.

READ | GDP deflator warning: How did the nominal growth weaken

Investment without productivity has limits

Public capital expenditure has been the backbone of the recent expansion. After years of balance-sheet stress, banks are lending again and corporate leverage has eased. This has been a necessary correction. But capital-led growth has limits when productivity growth remains modest.

India’s total factor productivity gains lag those achieved by East Asian economies at comparable stages of development. Logistics costs have declined, but land acquisition delays, contract enforcement issues, and regulatory uncertainty continue to weigh on firms. Enterprise surveys conducted by the World Bank routinely flag these frictions. Without stronger productivity growth, higher investment risks producing capacity without competitiveness.

Institutions matter more as the economy grows

Large economies are judged not only by outcomes, but by the credibility of their institutions. India’s macroeconomic management has improved in recent years. Inflation has largely remained within the tolerance band set by the Reserve Bank of India. Fiscal consolidation has resumed after the pandemic, and financial stability risks appear contained.

Yet concerns persist around data transparency and policy predictability. Revisions to national accounts, delays in household consumption surveys, and frequent changes in tax rules have unsettled analysts and investors alike. GST compliance has improved, but repeated rate adjustments complicate planning for small firms. As the economy grows, the cost of institutional uncertainty rises.

READ | India’s 8.2% GDP growth: Boom or sugar high?

Global integration without depth

India’s services exports have performed well, and digital public infrastructure has lowered transaction costs. Merchandise exports, however, continue to underperform relative to peers, limiting integration into global value chains. Trade negotiations have progressed slowly, and tariff structures remain complex.

Economic power in the modern world rests on manufacturing scale, technological diffusion, and the ability to shape standards. China’s rise was built on these foundations. India’s cautious trade stance offers short-term protection but restricts learning and competitiveness over time. A calibrated opening, tied to a clear industrial strategy, remains unfinished business.

A milestone that can still mislead

Becoming the world’s fourth-largest economy is an achievement worth noting. But it is not, by itself, a marker of economic power. That status depends on productivity growth, employment quality, institutional trust, and global integration.

The policy agenda is therefore clear. Labour-intensive manufacturing must be revived through stable trade policy and credible state-level reforms. Human capital outcomes in health and education need sharper attention. Data credibility and regulatory certainty must improve if investor confidence is to be sustained.

Political incentives favour celebrating rank. Economic outcomes depend on substance. Without a shift in priorities, India risks remaining a large economy that still falls short of great power status.