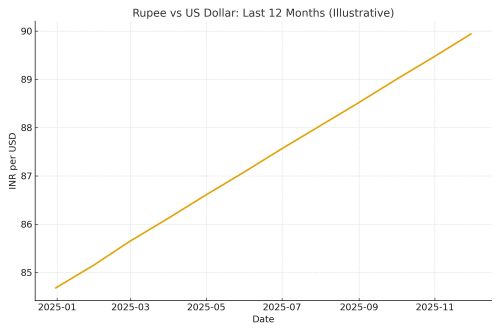

Rupee depreciation: The rupee breaching ₹90 per dollar has unsettled financial markets, but the fall follows a familiar script. Every few years, the currency confronts structural imbalances that RBI intervention can moderate but not reverse. Capital outflows, a risk-averse global cycle, a stronger dollar and uncertain trade negotiations with Washington have pushed the currency to its weakest level on record.

India’s balance of payments remains chronically tight, exporters are reluctant to hedge, and importers are scrambling for cover. The central bank is managing—rather than defending—the exchange rate. The result is a slow-burn depreciation that markets increasingly see as the base case for the year ahead.

READ | Higher education: How to turn scale into quality

Rupee depreciation: The scale of the slide

In less than a year, the rupee has moved from around 85 to above 90, its second-quickest fall since the 2013 taper tantrum. From mid-November’s 88.5, the currency has lost over 5%, making it the worst performer among major Asian currencies. Troublingly, the US Dollar Index has stayed below 100, signalling that the weakness is India-specific, not merely a global trend.

A crucial piece missing from most public discussions is the rupee’s Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER), published by the RBI. The latest data shows the REER hovering above 100, implying an overvalued rupee in real terms. This matters because an overvalued REER erodes export competitiveness and encourages imports. The nominal slide past 90 is therefore not just market unease; it is also a correction of a long-standing competitiveness gap.

Countries with overvalued REERs often experience periodic bouts of depreciation until real value aligns with economic fundamentals. India is no exception.

The balance of payments squeeze

Short-term volatility reflects investor withdrawals, widening trade deficits and hedging behaviour. But the deeper problem lies in the macro picture. A recent ICICI Bank note said India’s balance of payments will remain stressed through 2026, a view reinforced by persistent goods deficits exceeding $20 billion a month. Heavy import dependence in oil, electronics and intermediate goods keeps the current account under strain.

Large foreign exchange reserves—about $650 billion, according to the RBI—offer confidence, but they do not offset structural demand for imports. As long as the goods deficit behaves like a sinkhole, periodic currency pressure is inevitable.

Services surplus: A cushion with limits

India’s services surplus, especially in IT and business services, remains the one powerful cushion. The surplus now exceeds $150 billion annually, helping prevent a sharper rupee fall. But growth in IT exports has slowed as global tech spending weakens. GCC remittances, another stabiliser, plateau when global hiring cycles soften.

The message is clear: services can soften the rupee’s fall but cannot offset a goods deficit of this scale indefinitely.

External debt: The other pressure point

A currency under pressure must be examined alongside external debt liabilities, particularly short-term debt. RBI data shows that short-term external debt is around 45% of forex reserves, a critical IMF vulnerability metric. With External Commercial Borrowing (ECB) repayments rising between 2025 and 2027, refinancing will become costlier in a world of high global interest rates.

This debt overhang does not signal a crisis, but it does tighten the margin of safety. When markets know that corporate and sovereign refinancing needs are rising, they demand a weaker currency as risk compensation.

RBI’s crawling arrangement

The IMF classifies India’s exchange-rate regime as a “crawl-like arrangement”. The RBI allows a gradual weakening while intervening to prevent disorderly volatility. Even when the rupee touched ₹90.41, RBI intervention was modest; the late-session recovery to 89.98 came mainly from foreign banks selling dollars.

But intervention carries a cost. When the RBI sells dollars, it creates a short forward position. When it eventually buys dollars back to restore reserves, the market pushes the rupee weaker. Defence, therefore, plants the seeds of future depreciation.

The clearest signal lies in the forward market. The one-year forward premium has risen to over 92, from 90.8 in late October. Exporters who hedged earlier now suffer mark-to-market losses because the rupee has weakened much faster than expected. Many are avoiding new hedges, hoping premiums will improve. Importers, however, have no such luxury; a weaker rupee raises their landed costs immediately.

Why markets expect more weakness

The consensus view is not of a crisis but of prolonged softness. India’s macro fundamentals—moderate inflation, strong domestic investment and stable reserves—are not in question. But none change the basic arithmetic of the goods deficit, rising outward investment, slowing IT exports and higher external refinancing costs.

Unless India generates a sustained export surge or sharply reduces import dependence, the rupee will continue its gentle long-term slide.

Global winds will decide the pace

Much depends on the US Federal Reserve. Lower US interest rates would reduce the appeal of dollar assets, easing pressure on emerging-market currencies. But the Fed remains cautious, stressing sticky inflation. If rate cuts are delayed, the dollar will remain strong and the rupee weak.

A sudden improvement in global risk sentiment—similar to late 2020—could temporarily strengthen the rupee. But such events are unpredictable.

What lies ahead for the rupee

The most realistic outcome is a managed glide path. The RBI will continue smoothing volatility without defending any particular level. Importers will keep buying dollars on dips, reinforcing the downward trend. Corporates borrowing overseas will recalibrate plans around US rate expectations and hedging costs.

Short bursts of appreciation are possible. But without a structural shift in flows, the rupee will trend lower, and markets will adjust to this reality.

The rupee is not signalling a crisis; it is signalling the same old structural issues. A narrow export base, high import dependence, an overvalued REER, rising short-term external debt pressures and a services surplus that can only do so much.

Stability will not come from resisting depreciation. It will come from expanding manufacturing capacity, deepening export competitiveness, reducing energy and electronics import dependence, and aligning real exchange-rate fundamentals with market reality.

Until then, India must prepare for a world where the rupee keeps drifting—and where economic policy must work around that, not against it.