Skill development and demographic dividend: India enjoys a demographic edge that few nations can match, but youth alone does not create economic dynamism. With 65% of the population under 35, the country has a rare opportunity to turn its age structure into a source of long-term growth. The World Bank has long argued that countries benefit when the working-age population outnumbers dependents, improving the worker-to-dependent ratio and creating the conditions for faster expansion. Yet India’s window is narrowing. The ILO’s India Employment Report 2024 estimates that the share of youth will fall from 27% in 2021 to 23% by 2036, signalling that the peak of demographic advantage is already behind us.

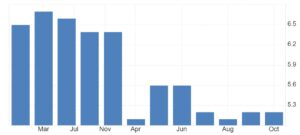

Headline labour market indicators offer a misleading sense of comfort. Unemployment has fallen from 8.03% in 2023 to 5.2% by June 2025, according to government data. But the real picture is more complex. Much of this improvement comes from informal employment, where wages are low and productivity gains limited. The bigger concern is whether India is creating the kind of jobs that can support sustained growth—formal, productive and aligned with emerging industry needs. Skill mismatches continue to hold back job seekers, even as firms complain about the lack of employable talent.

READ I COP30: India’s climate diplomacy after the Belém outcome

Training students for jobs that are disappearing

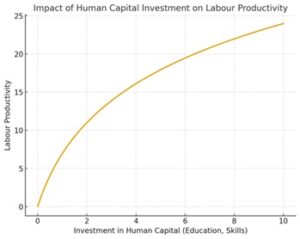

The situation aligns with what endogenous growth theorists like Paul Romer and Robert Lucas anticipated: human capital, not only demographics, drives productivity. Without deep investment in skills, education and innovation, the demographic dividend becomes a lost opportunity rather than an economic catalyst.

The world of work is shifting far faster than India’s institutions can adapt. Roles in artificial intelligence, data analytics, green technology and digital design are expanding, while positions in data entry, routine manufacturing and clerical tasks are disappearing. McKinsey estimates that 70% of jobs in India face automation risk by 2030, a stark warning for a country still training millions for roles that may not exist a decade from now.

India unemployment rate (%)

Yet academic curricula are revised only once every three years, even as technology cycles grow shorter. Public institutions, meanwhile, struggle with inadequate funding, shortages of trainers and outdated equipment. The UGC’s 2018 initiatives on innovation and entrepreneurship attempted to strengthen industry-academia linkages, but implementation has been uneven. Many universities fail to utilise their allocations effectively. Examinations continue to reward rote learning, producing graduates with high grades but limited ability to think critically or solve problems—skills that Joseph Schumpeter considered central to the process of “creative destruction”.

EdTech’s promise has not replaced systemic weaknesses

Edtech platforms were expected to disrupt this system, but most have simply digitised traditional shortcomings. Many replicate rote-learning models and commodify certifications without measuring learning outcomes. India’s 39th rank in the Global Innovation Index 2024 underlines the challenge. The entrepreneurial mindset necessary for Atmanirbhar Bharat remains thinly rooted outside a few urban pockets.

Employability data reinforce the message. The Mercer-Mettl India Graduate Skill Index 2025 reports that only 42.6% of graduates are employable, even though technical competencies—especially in AI, machine learning and cloud technologies—have improved. Non-technical skills such as communication, creativity and critical thinking remain major constraints. According to TeamLease Digital’s Skills Primer FY2025-26, firms expanding into tier-2 cities continue to face persistent talent shortages. With Global Capability Centres projected to create 1.2 million new tech roles by 2027, the gap between industry demand and workforce quality could widen sharply.

Skilling schemes focus on numbers, not outcomes

India has invested heavily in skill development, but outcomes have fallen short. The Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana has trained more than 1.6 crore youth, yet fewer than 15% have secured employment. The Prime Minister’s Internship Scheme, backed by ₹10,831 crore, has seen only 8,700 interns join during the pilot phase—barely 6% of offers, according to Lok Sabha data. Programmes such as the Deen Dayal Upadhyay Grameen Kaushalya Yojana continue to run diverse training courses in trades like tailoring and carpentry but lack robust curriculum standards and industry linkage.

The underlying weaknesses are systemic. Schemes measure enrolments and certifications rather than employability, wage gains or productivity improvements. Training centres often fail to communicate job roles, wages or locations, creating mismatched expectations and high attrition. Fund utilisation remains low, reflecting weak accountability at multiple levels. India’s approach contrasts sharply with countries like South Korea, Thailand and Singapore, where vocational programmes are co-designed with employers, partly industry-financed and tightly aligned with labour market needs. In South Korea, nearly three-quarters of vocational graduates move directly into industry roles.

PMKVY progress 2024

A holistic framework for skill development

Some efforts to address these gaps are under way, but they need scale, urgency and coherence. India’s curricula must be modernised to integrate life skills, digital literacy, vocational training and STEAM education. This requires continuous revision, not multi-year cycles. A strong mentoring ecosystem—built around peer learning, community engagement and trained counsellors—can support students beyond the classroom.

Incentives and penalties will need to be redesigned so that institutions and private players focus on measurable outcomes, not training volumes. Industry must play a central role in shaping vocational courses, while the government should mandate third-party audits to evaluate content, pedagogy and training quality. Monitoring and evaluation must move beyond counting trainees to tracking job placements, retention and earnings. Skilling can also benefit from behavioural tools such as gamification, which encourage learners to stay engaged through rewards and digital badges.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has called skill development the “backbone of self-reliance”. The goal is sound, but slogans cannot substitute for systems. India will become a developed nation only if it builds a workforce with the capabilities required for a fast-changing world. A future-ready economy is one that places human capital at its centre.

The shift India needs is clear: from certificates to careers, from training volumes to economic outcomes. The true demographic dividend will be realised not when millions complete short-term courses, but when every young Indian enters the labour market with the skills, confidence and adaptability needed to prosper. Only then will human capital become the foundation of sustained growth.

Sanchita Chatterjee is a Fellow and Tasmita Sengupta is Senior Research Associate at CUTS International, a leading policy research and advocacy group.