RBI MPC rate cuts: The headline reading that retail inflation has fallen to an eight-year low of 1.54 per cent in September is tempting — a rare opportunity to ease monetary policy aggressively. Wholesale price inflation has similarly softened, dipping to 0.13 per cent in September. Yet to capitulate to this temptation would be folly. While disinflation creates policy space, it must not lure the central bank into pre-emptive rate cuts that risk unmooring inflation expectations, undermining financial stability, and constraining future firepower. The Reserve Bank of India should resist the siren call of rapid easing; instead, it must proceed slowly and with data dependence.

The fall in prices is fragile, driven by transient factors such as a favourable base effect and softer food prices rather than a structural easing of inflation. Inflation expectations remain vulnerable; any premature rate cut could erode the RBI’s credibility and unanchor public confidence in its inflation target. Financial and external stability must also be guarded—easy liquidity risks fuelling asset inflation, capital outflows, and renewed pressure on the rupee. Policy space, above all, must be preserved; a gradual, data-driven approach is wiser than a hasty cut that may soon have to be reversed.

READ | SEBI’s block deal reform marks a market maturity test

Retail and wholesale inflation trends

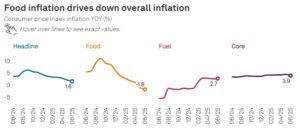

The drop in headline CPI to 1.54 per cent is partly a reflection of temporary factors — favourable base effects, sharp declines in food prices, and the delayed pass-through of recent GST rationalisation. Indeed, food inflation declined steeply to –2.28 per cent (deflation) in September. But core inflation (excluding food and fuel) has inched up to 4.5 per cent, driven principally by surging precious-metal (gold) prices. Meanwhile, the wholesale inflation (WPI) has already decelerated to 0.13 per cent in September.

The concern is that a large part of the headline disinflation is mechanical and transitory. Base effects will reverse, food supply shocks from monsoon variability may reappear, edible oil inflation remains elevated globally, and GST rate cuts (implemented late in September) may generate demand pressures and pass-through in future months. The RBI’s own projection has revised downward its CPI forecast for FY26 to 2.6 per cent, from 3.1 per cent earlier. Thus, to treat the current disinflation as a free lunch and rush to ease would expose the economy to the risk of reversion.

Inflation expectations must be anchored

A central bank lives or dies by credibility. If the RBI relaxes too quickly now, it may weaken its anchor over inflation expectations. The International Monetary Fund has recently warned that erosion of central bank trust under pressure to lower rates can lead to inflation expectations spirallingupward.

In the Indian context, households and firms form expectations of inflation based on past experience and central bank communications. The more aggressively the RBI cuts rates, the more it signals tolerance for inflation, and the more the public might revise up expectations of price increases. Once expectations slip, it becomes harder to rein them in, especially in a developing economy exposed to external shocks.

Recent empirical work, including machine-learning based analyses of the Phillips curve in India, show that inflation dynamics are nonlinear and sensitive to expectation channels and threshold effects. A precipitous policy reversal risks tripping those thresholds and destabilising inflation dynamics.

Financial stability, debt, and external vulnerabilities

Rapid easing carries risks not only to price discipline but also to financial stability. Lower interest rates fuel asset price inflation—real estate, credit, leveraged positions—and can encourage excessive risk-taking. In an environment of global uncertainty, such levers must be handled gingerly.

Furthermore, India’s external sector must not be overlooked. The rupee has recently experienced speculative pressure, prompting RBI intervention in the foreign-exchange market. A more dovish posture may encourage further capital outflows. Also, debt—especially corporate and household debt—when re-priced downward may lead to over-borrowing and leverage buildup.

Monetary easing is not without financial side effects. The central bank must calibrate cuts so as not to jeopardise financial stability or invite balance-of-payments stress.

Slow, conditional easing is smarter

One advantage of moving slowly is to retain options for future tightening or counter-shocks. If the RBI commits to deep cuts now, it may find itself cornered if inflation rebounds or external shocks (e.g. crude oil, global commodities, geopolitical flare-ups) hit. Moreover, the RBI’s room to manoeuvre is non-linear: initial cuts do more “damage” to credibility than later ones. By contrast, a gradual “insurance” cut of, say, 25 basis points—conditional on continued benign inflation and stable external metrics—would leave structural consistency intact.

In its last policy meeting (October 2025), the RBI kept the repo rate unchanged at 5.5 per cent, projecting GDP growth at 6.8 per cent and CPI inflation at 2.6 per cent. That is the prudent posture. It signals that the RBI stands ready to support growth, but only if disinflation is durable. The Monetary Policy Committee, in its minutes, has also flagged upside risks from base effects and global uncertainties, and emphasised careful monitoring of new data. That voice of caution must be sustained.

The temptation to cut rates quickly in response to falling inflation is understandable. But the art of monetary policy is in resisting temptation when the signal is noisy. The RBI’s primary goal is price stability in a flexible inflation-targeting regime; supporting growth is secondary.

In the present conjuncture, the central bank must lean toward gradualism, remain data-driven, and safeguard its long-run credibility. A 25 bps cut, if warranted, might be considered in December—but only if inflation remains anchored, inflation expectations are stable, the rupee is steady, and external headwinds pose no fresh threat. To ease too fast now would risk inflation bouncing back, destabilising expectations, and eroding policy credibility. The RBI would do well to look before it leaps.