Unemployment remains one of India’s most intractable policy challenges. Officially, an unemployed person is defined as someone actively seeking work but unable to find a job. By this measure, India’s jobless rate for July fell to a three-month low of 5.2%. Yet, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) placed the figure at 7.0%, and many economists believe even that may understate the problem. The key question is whether India’s labour metrics capture reality—or obscure it.

According to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), unemployment among those aged 15 and above fell from 5.6% in June, with a sharper decline for women. The figures are based on the Current Weekly Status (CWS) approach, which records activity in the seven days before the survey.

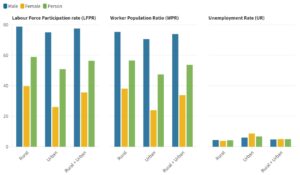

The data also show stark rural-urban contrasts. Rural youth unemployment dropped sharply in July, down 80 basis points to 13%, while urban youth unemployment edged up by 20 basis points to 19%. Overall, the rural unemployment rate for persons aged 15 and above declined to 4.4%, but in urban India it rose slightly to 7.2%.

READ I India’s ageing crisis has a gender angle

States and regional gaps

The newly revamped Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), extended to cover both rural and urban India, offered its first quarterly release. For April-June, youth unemployment touched 30% in Himachal Pradesh, the highest in the country, while Gujarat reported just 5.6%, despite having the highest youth labour force participation rate (LFPR) at 53.5%.

Unemployment raate (%) as per current weekly status

Nationally, unemployment for those aged 15 and above was 5.4%, with rural India at 4.8% and urban India at 6.8%. The LFPR varied widely, from Himachal Pradesh’s 70.3% to Delhi’s 43.5%. Across India, the average stood at 55%—77.3% for men and only 33.4% for women.

The employment landscape remains bifurcated. Agriculture continues to absorb the majority of rural workers, while services dominate urban employment. In April-June, 56.4 crore Indians aged 15 and above were employed—39.7 crore men and 16.7 crore women.

Why the numbers mislead

A Reuters poll in July highlighted widespread scepticism of India’s employment data. Over 70% of surveyed economists said official figures grossly underestimate unemployment, with actual rates ranging between 7% and 35%. The discrepancy lies in methodology. The PLFS counts anyone who has worked for even an hour in the preceding week as employed. By this definition, unpaid family labour and subsistence activities qualify as employment, making India’s statistics incomparable with international standards.

Anecdotal evidence underscores the scale of the crisis. In Maharashtra, a police recruitment drive drew nearly 1.8 million applicants for fewer than 18,000 posts. Such episodes suggest not only high joblessness but also the desperation for stable, formal-sector work.

Beyond joblessness lies the equally worrying issue of underemployment. Millions scrape by on irregular or low-paying work that cannot sustain even basic consumption. Official figures, which register any token activity as “employment,” fail to capture this precarious reality.

Structural fault lines and unemployment

Former Reserve Bank of India governor Duvvuri Subbarao has repeatedly stressed that the nature of job creation matters as much as the numbers. While finance and IT create wealth, they are not labour-intensive. Manufacturing, he argues, remains the only viable engine for large-scale employment.

Yet, despite India’s much-vaunted growth, employment generation has been anaemic. In FY25, leading banks cut back on hiring amid weak demand for personal, home, auto, and gold loans. Recruitment, where it occurred, was mostly backfilling rather than expansion, according to Teamlease Services. The Labour Ministry has defended its data, dismissing criticism as perception-driven, but the mismatch between growth and jobs is too stark to ignore.

The demographic dividend

The stakes are high. India needs to create 9 million jobs annually to absorb its expanding workforce. To deliver that scale of employment, the economy would need to grow at 12% a year—twice its current pace of 6-6.5%. Failure to do so risks squandering the demographic dividend, as a swelling working-age population finds itself without work or forced into low-productivity activity.

India can no longer afford complacency. Accurate, transparent data is the first step toward meaningful policy. Beyond that, job creation must shift from rhetoric to strategy—anchored in manufacturing, infrastructure, and services that absorb labour at scale.

Unless policymakers move beyond statistical comfort zones, India’s aspiration of becoming a global economic power will remain hamstrung by the absence of work for its people.