Some 27 million tonnes of nanoplastics—particles smaller than a virus—now swirl in the sun-lit surface of the North Atlantic alone. That single measure, confirmed last week in Nature, exceeds earlier estimates for all the plastic afloat in the world’s oceans. The finding is a siren that can no longer be ignored.

Humanity has manufactured more plastic since 2000 than in the entire century before it. Annual output, nudging 400 million tonnes, is projected to double by 2050 even as less than a tenth of plastic waste is recycled. What is not recycled is burned, buried or washed into rivers and seas, where it fragments into microscopic shards that infiltrate food, bloodstreams and placentas. Confronted with these cascading costs, the United Nations will convene a final negotiating round in Geneva from August 5 to 14 to craft a global treaty on plastics.

The negotiators face an inescapable verdict: tinkering with waste-management targets will be futile unless the treaty stems the flood at its source—curbing virgin polymer production—and regulates the 4,200 “chemicals of concern” embedded in everyday plastics. Ambitious, enforceable curbs are not optional; they are the minimum price of safeguarding prosperity.

READ I UPI goes global and smart with IoT-enabled payments

Unseen plastics deluge

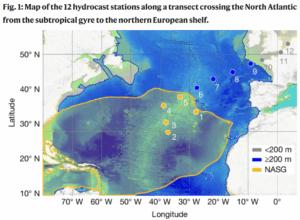

Public outrage has long centred on sea turtles ensnared in six-pack rings and seabirds stuffed with bottle caps. Yet the real menace lies in the fragments too small to see. The North Atlantic study reveals nanoplastic concentrations throughout the water column, with bottom-water samples still carrying five milligrams per cubic metre. Because they are neutrally buoyant, these particles travel vast distances, cross cellular barriers and shuttle toxic additives up the food chain.

A companion study has catalogued more than 16,000 chemicals used in or formed during plastic production, of which over 4,200 are toxic, persistent or bio-accumulative. In short, society confronts a ubiquitous cocktail of polymer dust and industrial chemistry that no waste-sorting line can filter out.

The landward picture is equally grim. Recent research detects microfibres in Arctic snow, in human lungs and even in breast milk. The health implications range from endocrine disruption to potential links with cancers. Each year of delay multiplies these risks, because plastic, unlike CO₂, does not disperse; it accumulates.

The hidden price tag

Cheap plastic thrives on the illusion of low cost, an illusion maintained by offloading its true burden onto fisheries, tourism, agriculture and public health. The OECD calculates that closing leakage pathways and building adequate waste infrastructure under a global ambition scenario would require an extra $600 billion between now and 2060—roughly what the world spends on bottled water in a decade. Those costs, however, pale beside the economic drag of polluted beaches, damaged gear and lost labour productivity from disease.

Moreover, production’s climate footprint is colossal; petrochemical plastics already account for 3–4 per cent of global greenhouse-gas emissions. Without intervention, they could consume a fifth of the remaining carbon budget compatible with a 1.5 °C world. Any serious climate strategy is therefore inseparable from a plastics strategy.

Why Geneva cannot blink

On one side of the negotiating table stands a “high-ambition coalition” of more than 70 countries—from the European Union to Australia—arguing for caps on plastics production, phase-outs of hazardous additives and extended-producer responsibility. Arrayed against them is the self-styled “like-minded group” of major oil and petrochemical exporters, led by Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia, which insists the treaty address only recycling and litter.

The obstructionism is shortsighted. Jobs touted as dependent on limitless polymer growth will anyway vanish as automation spreads and investors price in liability. Conversely, ambitious limits can catalyse whole new industries in reusable packaging, alternative materials and molecular recycling. The treaty must therefore enshrine three pillars: a timeline to peak and decline virgin polymer output, a global registry and licensing regime for hazardous additives, and legally binding national action plans subject to independent review. Anything less will license another generation of waste diplomacy.

National schemes show the way

Domestic initiatives demonstrate that sweeping action is both feasible and politically saleable. The EU’s 2019 Single-Use Plastics Directive mandates 90 per cent collection of beverage bottles by 2029 and a minimum 25 per cent recycled content from this year. Canada, Kenya, Chile and New South Wales have banned a spectrum of disposable items, while India’s national mission targets a 50 per cent reduction in single-use demand by 2030 through extended-producer responsibility fees.

Corporate behaviour is responding: refillable bottle sales are up double digits in several European markets, and global resin majors are pouring billions into chemical-recycling pilot plants. These efforts are no substitute for a treaty, but they explode the myth that production caps or additive bans are unworkable.

Experience also underscores the value of clear timelines. Europe’s deposit-return schemes pushed collection rates past 90 per cent within five years, while vague voluntary pledges elsewhere have languished below 30 per cent. Precision matters.

Financing and innovation

Redirecting subsidies is the simplest lever. Governments currently spend an estimated $20 billion annually on fossil-fuel incentives that directly underwrite virgin plastic. Reallocating even half that sum would capitalise a Global Plastic Transition Fund able to finance collection in the developing world, where 70 per cent of leakage originates. At the same time, levying a modest fee—say, two cents per kilogram—on virgin polymer sales would raise another US $8 billion a year, enough to spur circular-economy investments and clean up priority hotspots such as the Ganges, Mekong and Niger deltas.

Innovation is gathering pace. Enzyme-based depolymerisation of PET, once laboratory fantasy, now operates at industrial scale in France. Start-ups are converting agricultural waste into marine-compostable films, while digital platforms match scrap suppliers with buyers in real time, lifting recycling margins. Scaling such breakthroughs demands predictable policy anchors: stable carbon prices, minimum recycled-content standards and public procurement that favours low-toxicity materials.

An effective plastics treaty must lock in a global cap on virgin polymer production by 2030, followed by a one-third cut by 2040; create an open-access chemical safety registry backed by mandatory disclosure; impose extended-producer responsibility in every market; and establish a transition fund financed by polymer fees and diverted fossil subsidies. Trade rules should treat high-plastic-intensity goods the way border-carbon adjustments treat dirty steel—subject to tariffs unless producers meet circularity benchmarks. Without such provisions, ambition will migrate rather than multiply.

Geneva offers the final window before exponential curves of production, fragmentation and toxicity outrun the capacity of governance. The world knows the science and possesses the technology. What remains is the courage to legislate on the scale of the crisis. The cost of hesitation will be measured not in dollars alone, but in oceans turned into chemical soup and in human bodies laced with invisible shards. Ambition is no longer a virtue; it is the minimum standard of care owed to the future.