Foxconn’s midnight recall of more than 300 Chinese engineers from its iPhone plant outside Chennai is more than a corporate hiccup; it is a red flare over India’s industrial skyline. The retreat, widely linked to fresh export-licence checks in Beijing on precision machinery and to tighter rules on outward mobility of specialised technicians, threatens to delay the September launch of the India-assembled iPhone 17. Foxconn scrambled to fly in Taiwanese and American experts, yet the scramble itself underlines a sobering truth: Indian industry’s supply chains anchored in a strategic rival can be tugged at will.

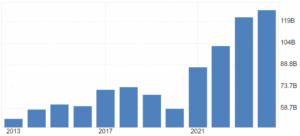

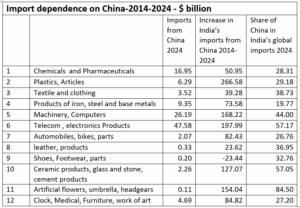

The merchandise deficit with China has swollen to almost $100 billion in 2024-25—roughly equal to the combined budgets of the health and education ministries. Customs data show imports climbing even as exports slide, leaving India with barely an eleventh of the bilateral trade pie it once shared more evenly. A GTRI report notes that Chinese firms now furnish well over 80 per cent of India’s laptops, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries. This imbalance is not a bookkeeping quirk; it is a systemic risk that can be weaponised whenever diplomatic winds shift.

READ I Five China-inspired fixes for India’s innovation gap

Lessons from Foxconn episode

Smartphone exports have become India’s new trophy statistic, yet a closer look at consignments bound for the United States reveals that up to half the printed circuit boards, memory chips and camera modules inside those phones still arrive in containers from Shenzhen or Guangzhou. Precise India-specific shares fluctuate by month, but industry trackers agree that Chinese suppliers dominate everything from silicon wafers to display glass.

Indian imports from China ($ billion)

The recent Foxconn episode lays bare the asymmetry: India provides the labour, the subsidies and market access; China retains the tooling, the engineers and the upstream components. Without deep domestic capacity in wafers, sensors and specialty chemicals, production-linked incentive schemes risk devolving into little more than large-scale screwdriver operations.

Life-saving APIs and fertilisers

India may style itself the pharmacy of the Global South, but up to two-thirds of its active pharmaceutical ingredients are estimated to be sourced from China; dependence for fermentation-based antibiotics such as erythromycin is higher still.

In agriculture, Beijing’s decision last month to tighten export controls on diammonium phosphate triggered a sudden price spike just as kharif sowing gathered pace. The spectre of politically sensitive fertiliser shortages—during an election year, no less—demonstrates how far commercial reliance can morph into public-policy vulnerability.

Batteries and solar panels

The ambition to become the world’s third-largest EV market collides with mineral realities. Battery-grade graphite, nickel-manganese-cobalt precursors and specialised separators overwhelmingly trace their origin to China. Solar modules tell a similar story: customs filings for FY25 show Chinese brands supplying close to 90 per cent of imported solar cells.

Tighter Chinese checks this quarter on rare-earth magnets and titanium components add another layer of fragility to India’s clean-tech aspirations. In effect, the sectors chosen to propel India into its green future could end up tethering growth to Chinese industrial policy unless the input mix is diversified swiftly.

Beijing’s graduated squeeze

Crackdowns on gallium and germanium in 2023, curbs on battery-grade graphite in 2024, export licences for rare-earth magnets in 2025, and now the tug on skilled labour: the rhythm is unmistakable.

Each move comes when India edges closer to policies that might dilute Chinese content—be it import-monitoring orders on laptops, the production-linked incentives for semiconductors, or a prospective trade pact with Washington. Beijing is not closing the tap; it is tightening the nozzle, reminding New Delhi that the cost of diversification will be paid up-front in delays, shortages and higher input prices.

A strategy for Indian industry

Reverse-engineer the routine: Roughly 90 per cent of current imports from China sit in the low- to mid-technology bracket—textile machinery, pumps, compressors, bearings, valves, even stationery. None is beyond India’s capabilities. Sectoral labs should be mandated to deconstruct the top 100 such products and place open blueprints in the public domain, paired with fast-track finance and time-bound incentives for local manufacturers willing to scale.

Go deep on components: Import substitution cannot end at outer casings. India needs vertically integrated clusters that design and fabricate key components—PCBs, camera modules, power-management ICs, battery cells—onshore. Japan’s post-war semiconductor leap and South Korea’s battery revolution were both driven by patient capital, tax breaks tied to value addition rather than assembly, and government-backed procurement guarantees. A similar template, anchored by long-term R&D grants and demand aggregation through public tenders, can help India move from screwdriver to silicon.

Screen strategic exposure: Telecom networks, power-electronics backbones and fintech rails warrant the same scrutiny that governs India’s defence procurement. Where Chinese ownership or single-supplier dependence threatens continuity, investment caps and phased localisation targets should be enforced. Simultaneously, partnership frameworks with Japan, Taiwan, the EU and trusted ASEAN economies must be broadened to ensure at least two alternative sources for every critical input.

Dependence on a strategic rival is not ordained by technology; it is the residue of policy drift, under-funded R&D and a tolerance for easy imports. The Foxconn recall, fertiliser squeeze and mineral curbs are unmistakable signals that the window to act is narrowing. A concerted push—spanning reverse-engineering, deep-tech investment and calibrated screening—can peel back layers of vulnerability while preserving the gains of global integration.

The objective is not autarky but autonomy: the capacity to ride out external shocks without derailing the growth trajectory. India’s demographic dividend and green-tech ambitions deserve nothing less than resilient, diversified supply chains rooted at home.