On the evening of November 21, an Indian woman from Arunachal Pradesh, travelling on a valid Indian passport and eligible for visa-free transit, arrived at Shanghai Pudong airport. She did what thousands of travellers do every day: joined the transit queue. But her journey stopped at the immigration counter. Chinese officials refused to recognise her passport because it listed Arunachal Pradesh as her place of birth. She was held for hours, questioned repeatedly, and allowed to board her onward flight only on November 25 — after consular intervention and sustained diplomatic pressure.

India issued a formal demarche. The ministry of external affairs stated that Arunachal Pradesh is an integral and inalienable part of India and that China had violated international norms governing transit passengers and consular protection. The statement was correct, but it told only part of the story.

This was not an isolated airport incident. It was a deliberate political act dressed up as border-control formalism. Passports, visas and maps have become tools in the sovereignty contest over Arunachal Pradesh. In the larger India-China relationship, where the military stand-off in Ladakh persists and political trust has eroded, even an airport desk becomes an arena for signalling power.

READ I India Afghanistan trade talks test Delhi’s regional strategy

A dispute fought through maps and documents

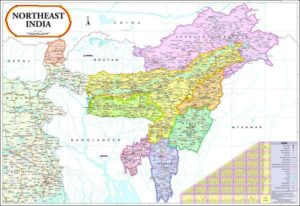

The sovereignty contest over Arunachal Pradesh has never been confined to the high mountain frontier. China calls the state Zangnan or South Tibet, disputes the McMahon Line, and rejects the boundary agreements that India regards as settled history. The dispute is older than the Republic itself, but the instruments used to prosecute it have changed.

For more than a decade, Beijing has issued stapled visas to residents of Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir, as if their Indian passports were incomplete proof of nationality. It has renamed towns and villages in Arunachal, including those far from any Chinese claim line. It has released new maps asserting maximal claims. It has pressed forward in Ladakh, triggering the most serious military stand-off in decades. And in 2016 and 2022, it challenged Indian patrols near Tawang, once again suggesting that the dispute is not dormant but alive.

Research from ORF, Brookings and the Lowy Institute has described these tactics as lawfare and mapfare: using legal language, bureaucratic acts and cartographic artefacts to delegitimise an opponent’s territorial claim without firing a shot. They are designed to alter perceptions of sovereignty, inch by inch, until political facts appear negotiable.

The passport is the newest frontier of this strategy. Under Indian law, a passport is proof of citizenship and of the territory over which India exercises sovereign authority. When Chinese officials refuse to accept an Indian passport because it mentions Arunachal Pradesh, they are not questioning a traveller’s paperwork. They are questioning India’s map.

Passports as instruments of power

A passport may appear to be a travel document, but it is in truth an assertion of statehood. It represents the authority of the issuing government and the boundaries within which that authority is exercised. International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) rules assume that states will honour each other’s passports unless there is a pressing security reason not to. Territorial objections have no place in airports and transit halls.

Yet states have increasingly used passports to expand or defend territorial claims. China printed the nine-dash line on its passports to advance its position in the South China Sea. It has refused regular visas to residents of disputed territories and offered stapled documents instead. It has denied boarding or transit to individuals whose passports misstate their place of birth, from Beijing’s perspective.

The Shanghai incident fits this pattern. It is the projection of China’s political map into the border-control practices of its airports. It forces foreign travellers to confront a choice: accept Chinese claims implicitly or be denied seamless transit. It turns an airport officer into an agent of geopolitical signalling.

India cannot afford to treat this as a routine bureaucratic dispute. It touches the core of citizenship, sovereignty and the dignity owed to every Indian national abroad.

India’s response: Adequate or minimalist?

India’s demarche was strong in language but modest in consequence. New Delhi has issued similarly worded statements after every episode of stapled visas, renaming campaigns or provocative maps. But beyond public protest, retaliatory measures have been limited.

This raises uncomfortable questions. Is a demarche enough when a citizen is told that her birthplace is not real? What message does New Delhi send to its own border residents if their documents are treated as negotiable? Does minimalist diplomacy discourage future incidents or invite them?

India has tools available, but it has preferred restraint. There are reasons for this. The two countries remain locked in a prolonged military stand-off in Ladakh. Trade ties persist but have narrowed. People-to-people contact is sparse. China has erected barriers to Indian companies and technology. Against this backdrop, every diplomatic move carries risks. The MEA seems determined not to escalate symbolic provocations into major ruptures. But restraint should not signal hesitation.

The wider India–China equation

The passport incident is part of a larger canvas. The border situation in Ladakh remains unresolved despite multiple rounds of military and diplomatic talks. China has expanded its infrastructure on its side of the LAC. India has built or upgraded over 60,000 kilometres of roads and bridges across the Northeast and the Himalayas in the last decade. Both countries now maintain heavy deployments, even in winter.

Trade ties have not recovered to pre-2020 patterns. India has restricted Chinese investment, banned dozens of apps, and tightened scrutiny of imports. China has, in turn, slowed market access and withheld clearances for Indian pharma and IT firms. Analysts from Carnegie, Lowy and IISS describe the relationship as one of “cold peace” or “armed coexistence”, marked by deterrence, limited engagement and deep mistrust.

Incidents in one domain are signals to the other. When China rejects an Indian passport from Arunachal, it sends a message not only about territorial claims but also about the tone it intends to set in the bilateral equation. Domestic politics on both sides amplify these signals. Nationalist sentiment flares quickly. Symbolic affronts attract more attention than the slow work of negotiation. This is how countries drift into confrontation without intending to.

Policy options: Firmness without escalation

India must protect its citizens while avoiding steps that deepen the fracture. A calibrated approach is possible.

Travel advisories and consular protocols must be updated. Citizens from Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir travelling through China should receive explicit guidance. Delhi must ensure they have immediate access to consular support. Moreover, India can apply reciprocal scrutiny to Chinese travel documents, within the boundaries of international law. Reciprocity is not escalation; it is a method of signalling that sovereign equality matters.

India should raise the issue in multilateral and aviation bodies. Transit rules must not become instruments of territorial assertion. Other countries, including in Southeast Asia, have faced similar problems. A coalition of concern may be possible.

Finally, Delhi should reinforce political outreach, development and connectivity within Arunachal Pradesh. A state is not defended only at its borders. It is defended in the confidence of its people. The more integrated Arunachal feels within the Union, the weaker the impact of external claims.

Deterrence by denial — preventing China from gaining advantage — and status signalling — asserting one’s own sovereignty through lawful but firm acts — provide a useful framework. India must use both.

The detention of an Indian woman at Shanghai Pudong was not an accident or a misunderstanding. It was a test of how India reacts when China challenges the legitimacy of its documents and the identity of its citizens. It was also a reminder that territorial disputes are no longer fought only on ridges and passes; they are fought in offices, databases, and airport queues.

India must move from episodic outrage to a consistent doctrine. It must defend its citizens, uphold norms, and respond with firmness that does not invite escalation.

And it must answer one question with clarity: If a citizen from the borderlands cannot rely on her own passport being honoured, what does territorial integrity mean in practice?