The economy of Afghanistan has become a textbook case of how politics can cripple markets and how the absence of trust can destroy value faster than any fiscal deficit. Four years after the fall of Kabul, the Afghanistan economy is still adrift — its reserves frozen abroad, its currency unstable, and its people trapped between aid dependence and isolation. What was once a fragile but functioning system has turned into an economy that runs on goodwill and inertia rather than policy and confidence.

Before August 2021, Afghanistan’s foreign-exchange reserves stood at about $9.8 billion. Of this, nearly $7 billion was parked with the US Federal Reserve and other overseas institutions. Those reserves were meant to stabilise the afghani, pay for imports, and anchor inflation. But once the Taliban took power, those funds were frozen. The Afghanistan economy is now left with an illusion of wealth on paper but no liquidity in practice.

By 2022, the usable reserves had fallen to a fraction of their nominal value. The World Bank estimated that even with emergency inflows, import coverage dropped sharply. This loss of access has meant the central bank cannot intervene meaningfully in currency markets, forcing traders and households into a fragile trust-based system of informal exchange. In ordinary times, reserves are a nation’s insurance against volatility. In Afghanistan’s case, they have become symbols of paralysis — assets that exist, but cannot be touched.

READ I AI disruption: India’s white collar jobs at risk

The afghani under siege

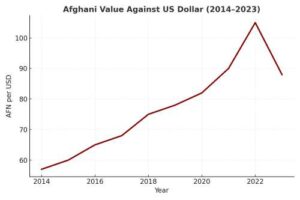

Currency tells a nation’s story more vividly than any statistic. The afghani, which traded near 80 to the dollar in early 2021, collapsed to about 130 by December of that year. Panic, not policy, drove the market. For a few months, remittances and humanitarian inflows offered some relief. But structural demand for dollars remained high because Afghanistan imports almost everything — from food to fuel to construction material. Inflation surged into double digits in 2022 before easing slightly. The central bank, deprived of its reserves and credibility, had few tools left.

The currency collapse fed a vicious cycle: import prices rose, eroding purchasing power; informal dollar markets expanded; and banks tightened withdrawals, deepening public distrust. Confidence — the most vital currency of all — evaporated.

Aid cuts and the collapse of formal finance

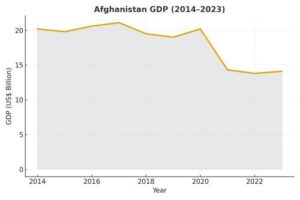

For two decades, Afghanistan’s state machinery ran on external aid. In 2020, grants financed over 75 per cent of public expenditure and nearly 40 per cent of GDP. When foreign donors withdrew after 2021, the Afghanistan economy lost not just money but the connective tissue linking its bureaucracy to the global system.

Banks were among the first casualties. Liquidity dried up, cross-border payments were interrupted, and the afghani deposit base shrank. According to the US Institute of Peace, the economy contracted by 20–30 per cent within a year. A “colossal collapse,” in their words.

Without recognition, the Taliban regime cannot access IMF Special Drawing Rights or new concessional loans. Sanctions complicate even humanitarian transactions. The Afghanistan economy has thus been pushed into a parallel world — officially sovereign, yet financially disconnected. The banking system now operates on rationed cash and humanitarian transfers. For an economy of nearly 40 million people, this is untenable.

The silent erosion of livelihoods

Behind these macro numbers lies a profound human crisis. The UN Development Programme estimates that 97 per cent of Afghans could fall below the poverty line if the situation persists. Food insecurity has become chronic; urban unemployment is spreading to the countryside.

In the absence of fiscal capacity, the de facto authorities rely on hawala networks and barter arrangements. That may keep trade moving, but it does not build institutions. A state that cannot tax, borrow, or spend transparently cannot sustain growth. The Afghanistan economy today runs more like a relief camp than a national system.

What makes the situation particularly tragic is that Afghanistan’s resource potential — minerals, hydropower, and strategic trade routes — remains untapped. Without legitimacy and investment, none of these can translate into real wealth.

What the world must learn

The lesson from the Afghanistan economy extends beyond its borders. A country can survive temporary shocks, but it cannot survive the loss of credibility. Economic sovereignty depends as much on confidence as on capital. For external actors, the policy dilemma is real. Unfreezing reserves without safeguards risks empowering an unrecognised regime. Keeping them frozen condemns ordinary citizens to destitution. A middle path — supervised release for trade and essential imports — may offer limited relief, but it is no substitute for a functioning state.

For domestic policymakers, the challenge is equally stark. Without an independent central bank, transparent fiscal accounts, and rule-based governance, the Afghanistan economy will remain a hostage to politics. Monetary policy cannot operate under fear; fiscal policy cannot function without legitimacy.

The world’s experience with fragile states — from South Sudan to Somalia — shows that isolation rarely produces reform. It only deepens informality and empowers black markets. Afghanistan risks repeating that cycle.

A fragile equilibrium

At present, the Afghanistan economy survives through humanitarian aid, remittances, and limited border trade with Pakistan, Iran, and Central Asia. The current-account deficit has narrowed not through exports but through import compression — a hallmark of distress, not stability. Inflation has eased somewhat, but purchasing power remains anaemic.

The country’s official GDP, last estimated around $14 billion, conceals the collapse of productive capacity. Banking credit is negligible; foreign direct investment has vanished. It is an economy operating at half power, sustained only by subsistence and resilience.

The international community may take comfort in the absence of a spectacular crash. But this is a slow-motion crisis. Economies do not collapse overnight; they fade into dysfunction. The Afghanistan economy is doing exactly that.

Afghanistan’s story is not just about frozen dollars or a weak currency. It is about the evaporation of trust — between citizens and the state, between banks and depositors, between the country and the world. Reserves, exchange rates, and aid flows are measurable; trust is not. Yet it is the most valuable reserve a nation can hold.

Rebuilding that trust will take more than money. It will require credible institutions, transparency in financial management, and gradual reintegration with the international system. Until then, Afghanistan will remain a cautionary tale — a reminder that without political legitimacy, even the best-laid macroeconomic frameworks can crumble overnight.