While battling Covid-19 with lockdowns, selective containment efforts, social distancing and medical interventions, India should draw on its past experiences of fighting with pandemics. A search in the past will also help assess the socio-economic and psychological aspects involved in dealing with pandemics. India had a tryst with another epidemic in 1994 – an outbreak of plague that originated in Surat, an industrial hub in Gujarat. India managed to contain the dreadful disease in a matter of four months.

Covid-19 is a much different disease from the plague that broke out in Gujarat. It is new to the world and there is no prescribed way to handle its spread, while the plague is one of the oldest epidemics that erased populations at different stages of history. The developments in science and technology enabled mankind to fight several epidemics and eradicate some. There is a lot to learn from earlier outbreaks — especially from their impact on the social fabric.

READ I Covid-19: Kerala Model is the success of decentralised democracy

The plague outbreak of 1994 produced enough data on the behavioural patterns of the people, mass media, and the government. However, it seems that policy makers fighting the new coronavirus have not gone through these materials. The plague outbreak produced panic across the society and made people behave differently. The health workers handled the crisis well.

The pneumonic plague infection was reported first from the living quarters of workers in Surat’s textile and diamond cutting units. Most of the workers were migrants who lived in unhygienic environment. The possibility of a quick spread of pneumonic plague generated a panic wave in Gujarat, Maharashtra and nearby places in no time. It all started on September 21, 1994 with the people of Surat speaking in hushed tones about an epidemic. The number of cases increased manifold in a few days and Surat saw a large exodus of people. Personal accounts say nearly 60% of the population left Surat in panic.

Rumours about the outbreak spread across the country fast and forced state governments to take precautionary measures. People started behaving irrationally in Surat and nearby places. They stared hoarding drinking water and antibiotics. The number of suspected cases of the pneumonic plague started multiplying very fast in eight states of India and the count crossed 5,000 by the first week of October. Maharashtra dominated the list of suspected cases with 2,793 cases, followed by Gujarat with 1,391 cases and Delhi with 749 cases. Five more states had 169 suspected cases.

READ I India’s migrant labour exodus and the missing trade unions

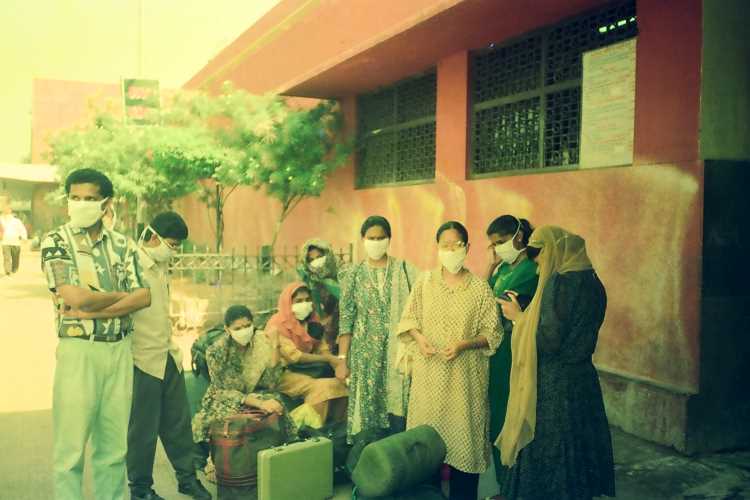

Reporting by mass media did more damage than the epidemic. The increasing number of suspected cases generated panic, even among those people who lived far away from affected places. New Delhi was badly affected by the panic and people started using face masks made of cloth. Hospitals in the national capital were flooded with suspected cases. Delhi grappled with fear and started looking at people from outside with suspicion. As a panic reaction, people started hoarding tetracycline, an anti-biotic effective against the plague. People thronged hospitals in panic even for mild cold and cough. Busy streets of big cities became empty by early evening.

The capital also experienced a sudden, but short-lived, initiative to clean up the city to keep the plague away. State chief minister and a few of his cabinet colleagues appeared on the streets with brooms. Though the initiative was a non-starter, people in Delhi’s urban villages took it to the next level by throwing dead rats on the streets.

The government was successful in containing the epidemic that could have claimed thousands of lives. Effective intervention of civic bodies and medical teams managed to limit the damage in terms of deaths and infections. By October 5, the authorities were successful in restricting confirmed cases to 167 from more than 5000 suspected cases. There were 53 deaths all over India due to the plague epidemic and 49 of them were from Surat.

READ I India must prepare for a bout of migration by doctors, medical staff

The experience of Surat offered an opportunity for the state and Central governments as well as public health authorities to understand and analyse the situation emerging from a sudden outbreak of an epidemic. In 1994, India did not have the benefits of technology that is on display today. People were kept informed through newspapers and state-run radio and television channels. There were a few private television channels that were under tight government control. So, the mindless sensationalisation of news was missing. No Internet and no social media meant less panic. Still, there was a lesson for future governments in the panic that paralysed the country.

The systematic intervention of the health workers and the strict surveillance and precautionary measures taken in urban areas were effective. After the plague in Surat, India experienced outbreaks of viral diseases like dengue and chikungunya, both spread by mosquitos, across the country, but the government and other public health machinery were successful in containing their spread.

Unlike the US and developed world, India has had enough experience in handling epidemics. India’s state and central governments have mechanisms to reach out to even remote locations. In most cases, epidemics originated at places that have health and hygiene-related issues.

The Covid-19 pandemic is a new experience to the world. It is a fast-spreading virus through the droplets from infected persons. The infection was first detected at Wuhan in China in late December, 2019. By mid-January, the whole world had knowledge about the nature of the virus, its ability to spread fast, and how it infects, as well as the available modes of treatment. The World Health Organisation declared Covid-19 an international health emergency in January end.

READ I Honey I shrunk the middle class, killed the Indian economy

In India, the first Covid-19 case was detected in Kerala – in a student returning from Wuhan — on January 29. After that, more cases started appearing in Kerala and other parts of the country among people returning from European countries such as Italy and Spain. The Kerala government, that had experience in dealing with the Nipah, acted early and decisively and managed to weather the first wave of Covid-19 infections.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a nationwide lockdown on March 24, India had just 730 positive cases and 2 deaths. Kerala was leading the list with 137 cases followed by Maharashtra with 125 and Karnataka with 55 cases. The lockdown was intended to control the rapid spread of the pandemic by restricting the movement of people. After a few rounds of lockdowns, in June, India decided to reduce the intensity of the steps. During the lockdown period, the country witnessed a rapid increase in the number of people and the death toll. Several experts were surprised by the government decision to lift the lockdown when the number of positive cases and deaths were on the rise.

Did India learn anything from the earlier outbreaks of viral epidemics and how much of the experience was put to use while dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. The experience gained from the plague was good enough when the pandemic was in the initial stages. The declaration of the lockdown without preparation and stalling of public life show that the leadership hadn’t learned anything from the past.

The lockdown was a great opportunity to prepare the health institutions, health workers, decision makers and the public to handle the pain of the pandemic. The leadership matters when the country goes through a crisis. The leadership should have anticipated the way the people and the media work in such situations.

READ I Crouching Dragon: Chinese influence set to rise in post-Covid global economy

The exodus of migrant workers in 1994, their mode of travel, the financial crisis and life experiences are well recorded. The news and features that appeared in the newspapers, observations and case diaries of health workers, officials, and government decisions are available in written and digital form. The disappearance of medicine and essential materials during the crisis due to panic buying was also reported in the newspapers.

India and many other countries got enough time to prepare themselves to prepare against the pandemic. Some states like Kerala and Odisha handled the first wave of the pandemic in a better manner. But an influx of people from other places is stretching the capabilities of the public health systems in those states. The political leadership of the country should have anticipated the level of crisis from the experience of other countries and prepared the health system with adequate stocks of medicine, testing apparatus, safety kits and makeshift hospital arrangements.

The outbreak of Covid-19 did not happen all of a sudden. It was not sporadic like the plague of 1994 and allowed ample time for preparation. Neglect of the public health system made it incapable of handling the crisis. Underspending in health and education has created a vulnerable population. Ideally, the government should have taken the lessons from the earlier outbreaks. The plague experience offered some relevant lessons, but the decision-makers preferred to ignore them. The current health crisis is the result of the government’s refusal to learn from the past.

(Dr P Ravindranathan teaches at the department of geopolitics and international relations of Manipal Academy of Higher Education. Views expressed in the article are personal.)

Dr Ravindranathan P teaches at the department of geopolitics and international relations of Manipal Academy of Higher Education.