The promise of the new Income Tax Act 2025 is simple: fewer disputes, fewer footnotes, and a clearer path for honest taxpayers. Paired with Budget 2025’s personal-tax reliefs, it reshapes the arithmetic of middle-class budgets while nudging behaviour away from exemption-hunting toward transparent, lower-rate taxation. The gains are real — especially for households earning up to ₹12.75 lakh — but the reform also narrows the role of tax incentives for savings and housing, and leaves capital-gains frictions that taxpayers must plan around.

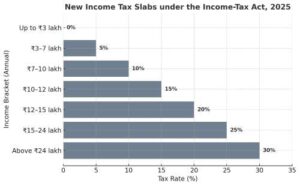

Parliament’s move is two-track. First, the new personal-tax slabs and a higher standard deduction — announced in the 2025 Budget—raise the effective zero-tax threshold for salaried individuals to ₹12.75 lakh under the new regime (this includes the ₹75,000 standard deduction and the Section 87A rebate). The top 30% rate now kicks in only beyond ₹24 lakh. That translates into sizeable savings for middle-income earners, with the government explicitly signalling a demand-boosting intent.

Second, the Income Tax Act 2025 is a structural rewrite—shrinking and reorganising provisions to cut litigation and ambiguity. It preserves the broad rate structure but simplifies drafting (tabulated rates, fewer cross-references) and is slated to take effect from April 1, 2026, after rules and systems are readied. Expect continuity in policy, but clearer language and navigation tools for taxpayers and practitioners.

READ I GST reforms unfinished without input tax credit fix

The Income Tax Act 2025: Who benefits

For salaried taxpayers choosing the new regime by default, monthly cash-flows improve immediately. With the standard deduction lifted to ₹75,000 and the 87A rebate aligned to the new slabs, the effective zero-tax band stretches to ₹12.75 lakh for salaried individuals. For typical urban households—two earners with combined income around ₹18–24 lakh—the shift delays entry into the highest bracket, freeing up cash for consumption or debt reduction.

The government’s own FAQs on Income Tax Act 2025 highlight the intent: the new regime is default, features concessional slabs, and limits deductions to a short list (standard deduction, select employer-linked items, family pension, etc.). The design reduces return complexity and the year-end scramble to “buy deductions.”

Fewer tax breaks for savings and housing

Relief comes with a philosophical pivot. The new regime trims the role of popular deductions that the middle class long treated as compulsory savings—think Section 80C investments, home-loan principal, and many insurance products. While some reliefs survive (e.g., standard deduction; limited housing-interest set-offs in specific circumstances; employer NPS contributions), the broader message is to decouple savings decisions from tax engineering. Households that relied on tax breaks to make home loans affordable must re-work affordability maths; the “EMI via exemptions” model is less compelling under the simplified regime.

That shift is deliberate policy. The government would rather lower rates with fewer carve-outs than administer an ever-expanding exemption forest. For the middle class, this means simpler planning—but it also demands financial discipline that is not nudged by the tax code.

Income Tax India

Income Tax Act 2025: Simplified capital gains law

Two important capital-gains changes shape middle-class investing. First, short-term capital gains on STT-paid equities (Section 111A) were raised to 20% in the 2024 reform round—reducing the tax advantage of high-churn trading. Second, long-term gains were realigned to 12.5%, with the surcharge on most capital gains capped at 15%, softening the burden at higher incomes. For salaried investors, this mix rewards longer holding periods and steadier allocation rather than tactical churn.

The Income Tax Act 2025 itself aims to clarify drafting and reduce litigation that has plagued capital-gains computation—one reason the government has emphasised shorter, clearer sections and tabulated schedules. But taxpayers should note a key wrinkle: special-rate incomes like STCG do not qualify for the 87A rebate that lifts salary incomes to zero up to ₹12.75 lakh. Even if salary is within the no-tax band, STCG will still draw tax. Plan equity withdrawals with that in mind.

Compliance: From footnotes to fewer disputes

The everyday experience of filing should improve. The government’s stated objective is a leaner statute to curb disputes—a pressing need given the backlog and the sheer volume of contested demands under the old law. A shorter, self-contained Act, with tabulated rates and fewer cascading explanations, should dovetail with pre-filled returns and portal nudges that have matured over recent years. For the salaried middle class—who primarily face TDS, a few allowances, and investment income—this could mean fewer notices and less professional dependence for routine filings.

Budget arithmetic acknowledges the trade-off: net revenue foregone from personal-tax relief is material (Reuters estimates around ₹1 trillion annually), but the bet is that higher disposable incomes and greater voluntary compliance will partly pay it back. That calculus is sensitive to growth and jobs—if consumption responds, the policy holds.

The middle-class playbook for FY26 and beyond

Three practical implications of the Income Tax Act 2025 follow:

Choose the regime with numbers, not habit: For many salaried households, the new regime will dominate once the standard deduction and higher thresholds are factored in. Legacy deductions must be unusually large to tilt the balance toward the old regime. Use a calculator before locking the choice for the year.

Re-baseline savings: Without 80C/80D et al. as decisive levers, re-design the monthly savings plan around goals, liquidity, and risk—not tax angles. Employer-linked benefits (NPS contributions, family-pension relief) and the ₹75,000 standard deduction still matter but are no longer the sole drivers.

Mind the capital-gains calendar: With 20% STCG and the 87A carve-out, impulsive equity churn can be costly. Prefer long holding periods that capture the 12.5% LTCG rate; when selling, bunch transactions to manage surcharges and remain attentive to set-off rules.

Lock in certainty, invest in service

The Income Tax Act 2025 will succeed in its efforts to reform if certainty and service quality improve alongside lower rates. Three steps will help:

Freeze the goalposts. Commit to no mid-year changes in personal-tax slabs or capital-gains rules for at least three years. Predictability reduces precautionary saving and unlocks consumption.

Publish plain-English guides and calculators mapped to the new Act’s sections, integrated into the portal. If the law is simpler, the interface must be simpler still.

Accelerate faceless dispute resolution for small taxpayers with strict time limits and automatic relief on minor mismatches. Litigation savings are part of the reform dividend; they must be realised quickly.

The New Income Tax Act 2025 and Budget 2025 together move India toward a lower-rate, low-exemption personal tax system. For the middle class, that means more cash in hand, fewer filing headaches, and a nudge toward sound, long-horizon financial decisions. The gains will stick if policy stays steady and administration stays friendly.