The government’s confirmation that 17,036 complaints have been registered under the Jal Jeevan Mission offers an opportunity to understand how a major national programme performs under pressure. The complaints have led to action against 2,397 officials and to the blacklisting of several contractors, according to the ministry of jal shakti. The numbers are significant because JJM is now the largest rural water initiative undertaken in India, with a mandate to provide a Functional Household Tap Connection (FHTC) to every rural household.

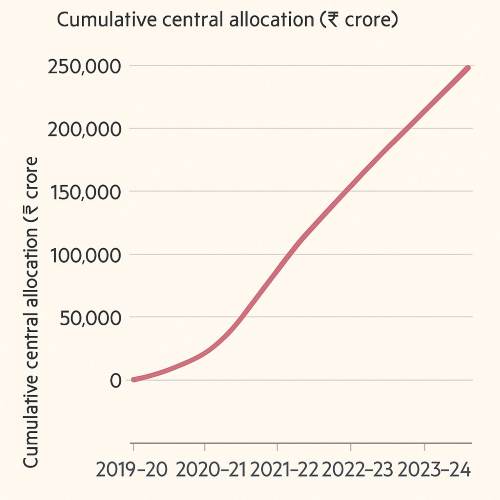

The financial support for the mission has expanded rapidly. Budget data show cumulative central allocations crossing ₹2.5 lakh crore since 2019. The rise in spending places a new burden on administrative systems that were not designed for projects of this scale. The central question is whether the governance structure can keep pace with the mission’s ambition. Evidence from the CAG, NITI Aayog, and international assessments of rural water systems suggests that the challenge lies less in funds and more in the durability of institutional arrangements.

READ I Sanchar Saathi app and the boundaries of state power

India’s experience with rural drinking water programmes predates the Jal Jeevan Mission by several decades. The Accelerated Rural Water Supply Programme (ARWSP), launched in the 1970s, sought to expand basic coverage but operated with limited monitoring tools. It was followed by the National Rural Drinking Water Programme (NRDWP), which introduced shared financing between the Centre and the states and a stronger emphasis on sustainability.

Reviews by the CAG and evaluations by the Planning Commission found persistent gaps in asset maintenance, water quality testing, and long-term functionality. JJM inherited these systemic issues but attempted a shift by focusing on household-level tap connections. The scale-up, however, has placed familiar strains on administrative systems that continue to evolve slowly.

Jal Jeevan Mission: The nature of irregularities

The 17,036 complaints received by the ministry point to recurring patterns in procurement, construction quality, and reporting practices. These patterns are not new; earlier rural water programmes faced similar problems. What distinguishes Jal Jeevan Mission is the size and speed of implementation, which has made these weaknesses more visible.

Procurement lapses account for a large share of the complaints. Several CAG performance audits have flagged instances where tendering norms were not followed or where contracts were awarded with limited competition. In certain districts of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, auditors found price deviations of 20–30 per cent from approved schedules. These findings echo long-standing concerns about weak procurement oversight in water and sanitation projects.

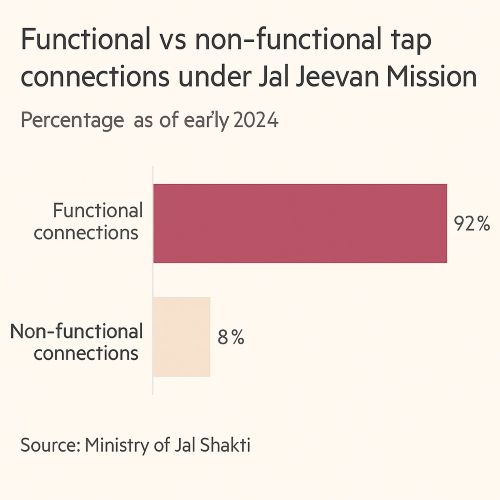

Quality issues form the second category. Reports from the states refer to leaking pipelines, incomplete overhead tanks, and non-standard materials. A World Bank review notes that poor construction quality is a leading cause of non-functional rural water assets in several countries. Misreporting of tap connections is the third area of concern. Independent verification exercises have found gaps between administrative claims and household-level reality. These discrepancies underline the importance of reliable field-level checks at a time when pressure to show progress remains high.

State-level patterns and why complaints cluster

The distribution of complaints across states provides useful administrative insights. Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha account for a substantial share of the reported irregularities. These are states where the mission’s scale is large and where institutional capacity is uneven.

Karnataka has undertaken one of the highest levels of spending under Jal Jeevan Mission—over ₹19,000 crore. The density of works in progress, combined with a wide contractor base, has placed pressure on local engineering systems. As a result, more complaints surface, not necessarily because performance is weak, but because the monitoring load is heavy.

Uttar Pradesh faces the challenge of size. With over 2.6 crore rural households targeted for coverage, its administrative structure must manage a scale unmatched by any other state. Gram panchayats often lack the engineering staff needed to inspect work or validate contractor claims.

Rajasthan presents a different pattern. The state’s dependence on long-distance transmission pipelines increases the technical complexity of projects. CAG findings show that water pressure in several schemes was inadequate, leading to quick deterioration of newly created assets. These state-level variations make one point clear: the scale of the mission is testing the limits of existing administrative capabilities.

Jal Jeevan Mission faces institutional gaps

The most persistent challenge arises from institutional gaps that have existed across earlier rural infrastructure schemes as well. Third-party audits are still not systematic across states. Many rely on internal engineering cadres whose ability to monitor large, simultaneous works is limited. A NITI Aayog evaluation notes that states often struggle to maintain updated asset registers, affecting their ability to track functionality over time.

Gram panchayats, designated as custodians of rural water assets, have limited financial and technical autonomy. Their capacity to check material quality or enforce contract provisions varies widely. This gap has created a vacuum in local accountability.

The dominance of a small contractor pool in many districts adds another layer of complexity. Where competition is limited, cost estimates tend to rise and oversight becomes weaker. International research, including World Bank studies, shows that between 30 and 40 per cent of rural water schemes in low- and middle-income countries face functionality issues within five years of construction. JJM’s experience so far suggests that India is not immune to this trend. As allocations grow, the demands on institutional design grow as well.

The rapid fiscal expansion under Jal Jeevan Mission has introduced new pressures on administrative systems. Central allocations have crossed ₹2.5 lakh crore since 2019, and annual spending has risen in line with the mission’s targets. This rise has shifted the role of departments from routine engineering oversight to large-scale project management.

The transition has not been smooth. Many state water supply agencies were designed for incremental expansion rather than accelerated construction. As allocations grew, gaps in contract management, quality assurance, and field supervision became more visible. The pattern mirrors what earlier evaluations of rural road and sanitation programmes have found: expenditure can increase quickly, but administrative capacity expands only gradually.

Fixing accountability: A rule-based approach

The rise in complaints calls for a review of the systems that govern procurement, audits, and monitoring. The experience of other centrally sponsored schemes offers some guidance.

Procurement must shift more decisively toward open competitive processes. Greater use of the Government e-Marketplace (GeM) can help improve transparency in material purchases. States can also publish tender outcomes in real time to enable public scrutiny.

Audit processes need strengthening. Independent, third-party technical audits should be mandatory for projects above a defined threshold. The Centre can link fund release to timely publication of these reports, a practice used in several large public works programmes.

Gram panchayats should be given formal authority to certify completion and monitor functionality. Evidence from community-managed water schemes—particularly in Kerala—shows that stronger local ownership improves maintenance and reduces downtime.

Finally, payment structures need realignment. Linking contractor payments to 12-month functionality, rather than to completed construction, can reduce the incentive to prioritise speed over quality. These changes will take time, but they are necessary for a mission that depends heavily on field-level execution.

The Jal Jeevan Mission represents a major administrative undertaking. The 17,036 complaints recorded so far highlight the demands placed on procurement systems, audit mechanisms, and local governance structures. The rise in central allocations has ensured financial support, but institutional capacity has not kept pace. The challenge now is to build systems that can maintain asset quality and ensure long-term functionality.

Strengthening audits, improving procurement, enhancing local oversight, and aligning incentives with outcomes will be essential. The mission’s success will depend not only on funds spent or connections reported, but on whether India’s administrative systems can support delivery at this scale.