Microfinance institutions remain the most durable bridge between formal banking and households that the system still fails to see. For millions of low-income families, an MFI loan is the first interaction with organised finance. Yet the sector is now trapped in a paradox. Asset quality is improving under tighter regulation, but lending activity is contracting. Stability has returned, but growth has not.

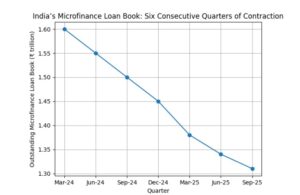

The numbers are unambiguous. Industry data compiled by the Reserve Bank of India show that the combined microfinance loan book has declined for six consecutive quarters, falling from about ₹1.6 trillion in March 2024 to roughly ₹1.31 trillion by September 2025. Several million borrowers have exited the system in that period. In a business model built on repeat lending and long relationships, that erosion matters more than headline portfolio quality.

READ | Microfinance faces credit stress as delinquencies surge

This contraction cannot be understood without looking at household cash flows. Elevated food inflation, uneven rural wage growth, health shocks and climate-related disruptions have strained repayment capacity in many districts. Migration-linked incomes remain volatile. Microfinance stress is therefore not only a credit-discipline story; it is also a livelihoods story. When household buffers thin, even well-structured loans begin to look risky to both borrower and lender.

Discipline is back—by design

Regulation has done what it was meant to do. RBI’s cap on the number of lenders per borrower, alongside income-linked loan limits, has sharply reduced over-indebtedness. Credit bureau data show a steep fall in borrowers carrying four or more microfinance loans. Portfolio at risk ratios have improved across most large NBFC-MFIs. This is not accidental; it is the outcome of deliberate regulatory choices by the central bank.

READ | Microfinance: Tamil Nadu Bill targets predatory lending, coercive action

Better asset quality should have unlocked liquidity. It has not. Banks and investors remain cautious because profitability is under strain. Higher credit costs, interest reversals on stressed accounts, and rising compliance expenses have compressed margins. For smaller NBFC-MFIs, the price of caution is steep. Growth has been traded for balance-sheet comfort, and the trade-off is visible in falling disbursements.

One reason confidence has not returned lies in funding markets. NBFC-MFIs borrow at rates that rose sharply during the tightening cycle, but regulatory and reputational constraints limit how far these costs can be passed on to borrowers. At the same time, securitisation and loan-assignment appetite has weakened, reducing balance-sheet flexibility. Spreads have narrowed from both ends, leaving lenders solvent but hesitant.

Trust at the borrower level

Field reports point to a subtler risk. Some borrowers who can repay are delaying payments, uncertain whether repayment will lead to renewed access to credit. In joint-liability groups, this uncertainty weakens peer discipline. The phenomenon is not yet systemic, but it signals a fragile trust equation. Microfinance runs as much on expectations as on spreadsheets, and expectations are unsettled.

READ | Microfinance in India: Debt trap or a lifeline for the under-banked

The political economy is turning adverse. With several states entering election mode in 2026, memories of past loan-waiver announcements have resurfaced. Even vague political signals can disrupt repayment behaviour among vulnerable households. MFIs and their lenders have flagged this risk to policymakers. Past election cycles show that these fears are grounded in experience, not paranoia.

Why banks are pulling back

Universal banks and small finance banks play a dual role—as direct lenders to microfinance clients and as wholesale funders of NBFC-MFIs. Their risk appetite has narrowed under regulatory scrutiny and post-pandemic caution. Senior bankers insist credit is available to well-run MFIs, but screening has become far tighter. Many eligible borrowers are excluded not because they are uncreditworthy, but because lenders are managing portfolio optics. The gap between inclusion rhetoric and outcomes is widening.

One practical reform lies in credit information access. A large share of microfinance is delivered by not-for-profit Section 8 companies embedded in local communities. These entities remain outside the formal credit bureau framework because they are not directly regulated by the RBI. Allowing them controlled access to credit information companies would improve borrower assessment and reduce systemic risk without diluting oversight.

Guarantees are not a cure

Industry bodies have renewed calls for a microfinance credit-guarantee scheme, with a proposed corpus of around ₹20,000 crore. Such a backstop could, in theory, encourage banks to lend by sharing downside risk. In practice, design and timing remain uncertain. With the Finance Ministry focused on fiscal consolidation ahead of the Budget cycle, a rapid rollout is unlikely. Guarantees can buy time; they cannot replace viable business models.

The pre-pandemic years showed the cost of rapid expansion detached from borrower income. The current slowdown, while painful, offers a chance to reset incentives—towards steadier growth, income-linked lending, and products beyond plain credit. But this reset will fail if it hardens into exclusion. The responsibility is shared. Regulators must protect borrowers without freezing risk-taking.

Banks must separate genuine risk from reputational anxiety. State governments must signal clearly that credit contracts will not be politicised. Financial inclusion fails not only when loans turn bad, but also when credit quietly disappears.