A large share of Indian households remains one serious illness away from financial distress. The financial services secretary recently met insurers, hospitals and industry associations to address the rise in premiums and medical inflation. The urgency of this meeting reflects the lived reality of most families. Despite a decade of public schemes and a fast-expanding private insurance market, out-of-pocket expenses continue to dominate how Indians pay for healthcare. The pandemic exposed these vulnerabilities. Recent data and international experience point to the need for a fundamental redesign of health financing so that illness does not translate into acute economic insecurity.

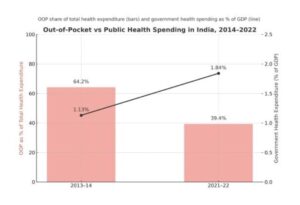

According to the latest National Health Accounts, out-of-pocket spending accounted for 39.4 per cent of total health expenditure in 2021–22. This represents a substantial fall from 64.2 per cent in 2013–14, driven partly by public programmes such as Ayushman Bharat PMJAY and the national dialysis scheme. However, the level remains high for a country seeking to broaden access to essential care. Many households still struggle to meet even basic treatment costs.

READ | Will RBI’s repo rate cuts bring relief to homebuyers?

Limits of current insurance coverage

Government health expenditure has increased in per capita terms. Yet macro indicators tell only part of the story. Households continue to shoulder most hospitalisation expenses. Surveys by the ministry of statistics show that rural families pay close to 92 per cent of hospitalisation costs, while urban households meet about 77 per cent from their own pockets. Public hospitals such as AIIMS operate significantly over capacity, forcing many patients towards private facilities where treatment is more expensive.

Insurance offers limited financial protection. Only about one-third of total medical spending is covered by insurers or the state. Penetration remains low outside formal employment, and common coverage caps of Rs 3–5 lakh have become inadequate in the face of rising treatment costs. Even insured patients often confront the failure of cashless treatment at the point of care. Coordination delays between insurers and hospitals mean families end up paying directly, especially during emergencies when approvals matter most. Concerns about inflated billing further erode confidence, as charges often exhaust policy limits early.

The vicious circle of underinsurance

Medical inflation is rising at about 14 per cent a year, outpacing general inflation and eroding the real value of insurance coverage. Hospital charges have increased sharply, prompting insurers to raise premiums in response. Households face difficult choices: absorb higher premiums, reduce coverage, or exit the insurance market entirely. Each path weakens financial protection.

Underinsurance reinforces the cycle. Families defer treatment, borrow at high interest rates, or cut essential consumption to meet health expenses. Catastrophic illnesses push many into long-term debt. Persistently high OOP spending thus reflects not only administrative inefficiency but also structural weaknesses in how India finances healthcare.

India’s workforce shortages intensify cost pressures

A critical structural issue driving costs — and missing from most public debates — is the severe shortage and uneven distribution of healthcare professionals. India has approximately one doctor for every 834 people, according to the National Health Profile, but states differ widely in availability. Some have barely half the national average. The nurse-to-population ratio remains around 1.5 per 1,000 people, well below the WHO norm of 3. District hospitals across the country report shortages of specialists exceeding 70 per cent.

These gaps have direct implications for affordability. Patients often bypass primary centres and district hospitals due to staffing constraints and turn to private providers even for routine care. Private hospitals, facing rising labour costs to attract and retain staff, pass these costs on through higher treatment charges. Workforce shortages therefore feed into medical inflation, widen regional disparities in access and worsen the financial burden on households.

Why standard treatment protocols matter

The government has asked insurers and hospitals to move towards standardised treatment protocols, common empanelment norms and seamless cashless claim processes. Standardisation is central to controlling both cost and quality. The Indian Council of Medical Research, the National Health Authority and the World Health Organisation have jointly developed 157 Standard Treatment Workflows (STWs) across 28 specialities. These workflows encourage evidence-based care, discourage unnecessary diagnostics and limit discretionary billing.

If implemented consistently, STWs could stabilise claim patterns, reduce premium volatility and minimise surprise billing. The challenge lies in uniform adoption across providers, transparent pricing and close regulatory oversight.

Global models of universal health coverage

India’s reliance on OOP payments resembles what health economists describe as the “Out-of-Pocket Model,” where individuals pay at the time of service. This structure consistently leads to financial distress and delayed care.

Countries that have moved towards universal health coverage typically adopt one of three models. The Beveridge model relies on tax-funded, publicly provided healthcare, as seen in the UK and Scandinavia. The Bismarck model uses mandatory social insurance funds and negotiated fee schedules, common across continental Europe and Japan. The National Health Insurance model features private providers but a single public insurer, as in Canada, Taiwan and South Korea. Each model reduces household exposure to catastrophic costs while offering predictable financing.

A shift towards a Beveridge- or NHI-type system would sharply reduce OOP spending in India. But this would require far higher public investment, stronger provider networks and political consensus. Public health expenditure remains around 1.3 per cent of the GDP — well below global benchmarks.

Incentives, regulation and the public provision gap

Improved clinical guidelines alone do not reduce unnecessary care. Provider incentives and payment mechanisms shape behaviour. Hospitals paid on a fee-for-service basis have little reason to limit diagnostics or admissions. Reform must therefore focus on aligning incentives with efficient care. Payment systems need to delink revenues from volume and redirect them towards outcomes.

India also requires a substantial expansion of public hospital capacity. Without strong public alternatives, private-sector pricing pressures will remain unchecked. Policymakers increasingly recognise that uncontrolled medical inflation, opaque pricing and fragmented empanelment norms are unsustainable. Standardisation is necessary, but not sufficient, to address these deeper problems.

India needs a health financing system that shields households from unpredictable medical shocks. Reducing OOP spending is central to that goal. Standardised workflows, transparent pricing and reforms in insurance design are important steps. However, durable progress requires broader reforms. Public investment must increase. Provider incentives must change. Regulatory oversight must be strengthened. And public hospitals must expand their capacity and reliability. Without these structural shifts, millions of Indians will remain exposed to health-related financial risks that threaten economic security and long-term mobility.