India has committed to universal health coverage for all by 2030. The promise is simple: everyone should be able to use the health services they need, when they need them, without financial hardship. That includes the full continuum, from health promotion and prevention to treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care.

Universal health coverage is often read as a financing promise. It is also a behaviour and systems promise. Primary care must be accessible and credible. But citizens also need practical support to prevent disease and protect health. That responsibility cannot be outsourced to individuals alone. The state has to shape conditions in which healthier choices are easier to make and sustain.

READ I India’s global health opportunity amid US withdrawal

India’s health coverage beyond insurance

India has expanded access through the routine public health system and newer schemes such as PMJAY, free drugs and diagnostics, and wider coverage through ESIC. Yet more than half the population still does not access structured health insurance.

The larger gap is not insurance. It is the design of services. Current health services remain thin on health promotion and prevention, and weak on continuity of care. They are organised for episodes of illness, not for keeping people well.

READ I Menstrual health is enforceable right after Supreme Court ruling

Universal health coverage and NCDs

Non-communicable diseases are rising. Costs of care are rising faster than budgets. The demand-supply gap in curative services will widen as India ages and urbanises. Prevention is no longer an add-on. It is the only scalable strategy.

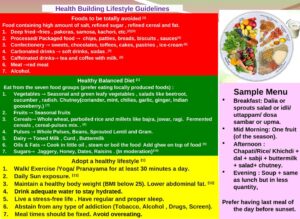

- A structured way to translate prevention into practice is to push the six pillars of lifestyle medicine:

- Whole-food, plant-based nutrition

- Physical activity, including yoga

- Restorative sleep

- Stress management

- Social connection

- Avoidance of risky substances

A recent “traffic light” guideline, designed for the Indian context, offers a usable template for public action.

READ I Healthcare allocation rises, but structural gaps remain

Government action on healthy lifestyles

Shifting entrenched lifestyles needs concerted action, led by government. Six steps are immediate and implementable.

Mass awareness with credible role models. Public icons should be discouraged from endorsing products that are known to harm health. Government should adopt an explicit health-promotion policy and enforce it consistently.

Ultra-processed foods as a policy target. Run sustained campaigns on their risks and tax such foods more heavily. The Economic Survey 2025–26 has already argued for sharper restraints—curbs on advertising and a higher tax treatment for ultra-processed foods. In parallel, make minimally processed, whole, plant-based foods cheaper and easier to access. Regulators are being pushed in the same direction: on February 10, 2026, the Supreme Court asked FSSAI to seriously consider front-of-pack warning labels on packaged foods.

A preventive-promotive package in health financing. Define a standard package built around the six elements of lifestyle medicine. Provide it through the routine health system, and cover it under PMJAY and ESIC. Private insurers should be required to include it as a basic entitlement.

Urban design for daily physical activity. Build dedicated cycling tracks and safe footpaths along major transit corridors in urban and peri-urban areas. Encourage workplaces and institutions to allocate time and space for collective physical activity. A public “healthy workplace” rating, on the lines of green ratings, can create competitive pressure.

National Medical Commission and lifestyle medicine training. The NMC should recognise lifestyle medicine as a specialty, enable courses, and require family physicians to build competence in preventive counselling.

National Digital Health Mission

Expand NDHM records to include preventive check-ups and self-reported health practices that citizens can update periodically. Build an add-on application that uses AI to flag disease risk early and nudge course correction.

The digital rails already exist: ABDM’s ABHA architecture is now the default pathway for portable records, and official mission documentation places the emphasis on a national ecosystem rather than isolated facility-level digitisation.

Many developed countries invest heavily in health promotion and disease prevention because it reduces avoidable demand on hospitals and budgets. India cannot meet universal health coverage ambitions through financing and treatment alone. If the aim is a healthier population by 2030, prevention must move from rhetoric to a working architecture.

Dr Rakesh Sarwal is a leader in public health, public policy, and planning with more than three decades of experience in governments in India.