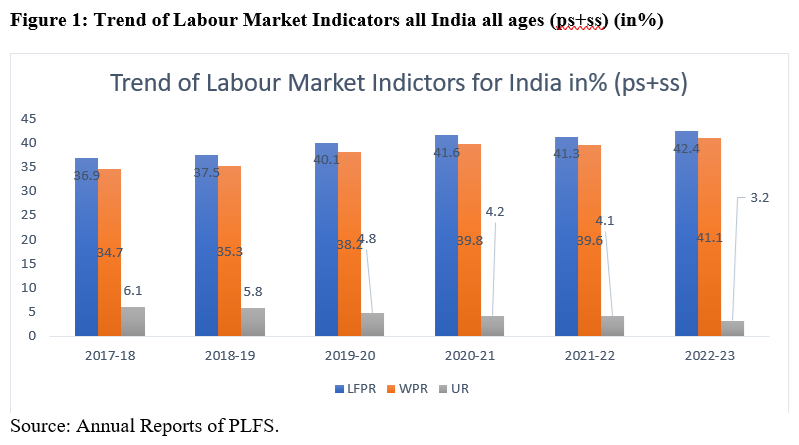

The Periodic Labour Force Survey 2022-23 highlights a steady increase in the overall labour force participation rate (LFPR) in the country, except for a marginal decline in 2021-22. The LFPR reached 42.4% in 2022-23, up from 36.9% in 2017-18. The workers’ population ratio (WPR) grew faster than the LFPR, rising from 34.7% in 2017-18 to 41.1% in 2022-23. Consequently, the unemployment rate dropped to 3.2% in 2022-23 from a high of 6.1% in 2017-18 (see Figure 1).

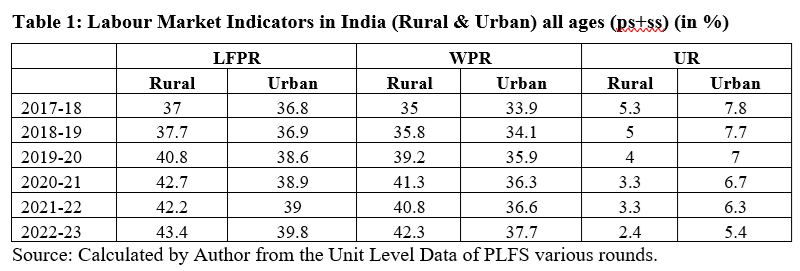

This encouraging performance is observed in both rural and urban areas, with rural areas experiencing a significant increase in LFPR and WPR. The convergence of rural LFPR and WPR implies a steady decline in rural unemployment. The overall decrease in unemployment can be attributed to a significant increase in rural employment. On the other hand, urban LFPR and WPR converged until 2019-20, but after that, the gap between them remained relatively constant, resulting in constant urban unemployment (refer to Table 1).

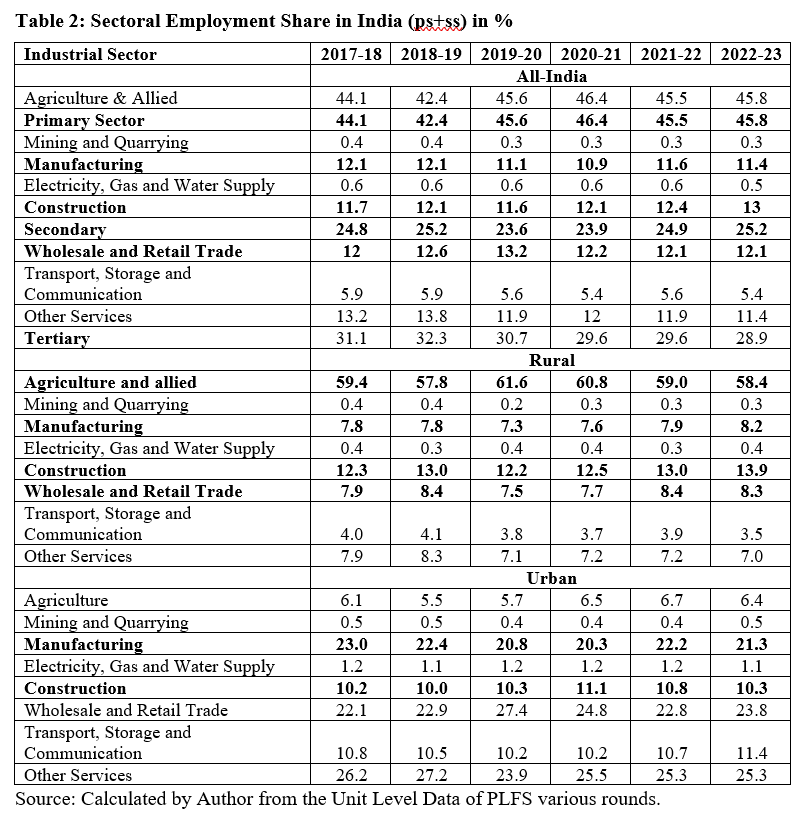

A sector-wise analysis of employment allocation across India reveals that the share of the services sector has gradually declined by 2.2% from 2017-18 to 2022-23. This decline has been largely compensated for by the primary sector (1.7%) and, to a lesser extent, the secondary sector (0.5%). Furthermore, when we examine employment by sub-sector classification at the all-India level, we uncover some intriguing findings.

READ I IT sector slams the brakes on hiring amid economic uncertainties

Three sectors behind low unemployment

Only three sub-sectors have been driving employment growth in recent years: agriculture and allied activities, construction, and wholesale and retail trade. This suggests that these sectors have been less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and have experienced the fastest rise in employment (see Table 2).

The annual Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO) replaced the previous quinquennial employment and unemployment surveys in fiscal year 2017-18. This survey provides numbers to analyse annual trends in the labour market. The sixth annual PLFS data and report, covering the survey period from July 2022 to June 2023, were released on October 9, 2023.

The emergence of the wholesale and retail trade sector as the second-largest provider of employment after agriculture in 2022-23 is a surprising development. This sector has also shown positive growth from 2017-18 to 2022-23. These trends indicate that manufacturing and services are still grappling with the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and have not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. Excluding wholesale and retail trade, which recorded impressive employment growth up to 2019-20 but then stabilized, only agriculture and construction activities are driving job growth in the country (see Table 2).

This emerging pattern raises several perplexing questions. Has the rural sector become the primary engine of employment growth in India in the post-COVID years? What are the major economic activities in rural areas driving this employment growth? Is the reliance on agriculture increasing, and is it sustainable?

A clearer picture of employment trends emerges when we consider rural-urban and sub-sector breakdowns. The share of rural areas in employment generation in the country is at an all-time high compared with urban areas. However, the growing gap between rural and urban WPR in recent years can be attributed to the fact that job losses during the COVID-19 pandemic forced people to return to their villages and engage in whatever available activities were present in rural areas, leading to a significant increase in rural employment.

There has been a noticeable surge in employment in the primary sector during the COVID-19 period in rural areas, indicating that agriculture became the last resort for employment, accounting for 61.8% of total rural employment in 2019-20, up from 57.8% in 2018-19. However, this trend began to decline after 2019-20 and returned to pre-COVID-19 levels (58.4% in 2022-23). This suggests that those who turned to agriculture during the pandemic found it unsustainable as a source of livelihood.

The likely explanation is that migrants returning to their villages during the COVID-19 pandemic initially resorted to agriculture as a subsistence option. However, as the impact of the pandemic waned, they found agriculture to be less lucrative due to its seasonal nature, greater lag in income, and lower wages compared to the non-farm sector, which provides higher and more consistent wages. Among non-farm activities, construction emerged as the leading employment provider in rural areas, growing faster than in urban areas (see Table 2).

As the situation improved, labour, mainly returning migrants, began to look towards the non-farm sector to alleviate their daily hardships. Among various non-farm sectors, the rapidly growing construction sector became a preferred employment destination. However, some return migrants who were comparatively better off in terms of land ownership (ancestral) and capital (accumulated from pre-COVID earnings) chose to venture into the manufacturing sector by starting their own businesses, utilising the expertise and skills they had acquired from their previous work in urban areas before the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is evident from the increase in rural manufacturing employment, which rose from 7.8% in 2017-18 to 8.2% in 2022-23. The construction sector is the only sector that has been least affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The construction sector’s share in total output (Gross Value Added, GVA) increased from 8.01% in 2017-18 to 8.41% in 2022-23 at constant prices. The growth of the construction sector in GVA has been in double digits in the last two financial years, averaging 12.42% at constant prices. In rural areas, the construction sector has been the fastest-growing sector in recent years.

Coupled with the overall demand for construction and the additional demand generated by the increasing non-farm activities in rural India in the post-COVID era, particularly from growing rural manufacturing and other non-farm activities, rural construction employment is experiencing a boom. The employment share in the rural construction sector of total rural employment increased from 12.3% in 2017-18 to 13.9% in 2022-23. Consequently, the improvement in the employment scenario is not driven by manufacturing or services but by the construction sector.

It should come as no surprise that in the near future, the share of agriculture and allied activities, along with construction, will continue to increase due to the constrained performance of the manufacturing and services sectors. However, this also poses some threats to the job market. There is a high probability that underemployment will rise as more people seek employment in the agriculture sector. The precarity of daily wage earners is also expected to increase, as jobs in the construction sector are mostly project-based and short-term with poor labor standards. There is a risk that this positive trend may come to an end, as there is a limit to the growth of employment in the agriculture sector.

Based on these trends, we can conclude that the rural sector is driving employment growth in the post-COVID years, primarily led by the construction sector. However, it would be accurate to say that dependence on agriculture is not sustainable, given the variability of monsoons, uneven rainfall distribution, and the El Niño effect. A coping strategy of enhancing rural entrepreneurship and industrialisation may provide a more sustainable livelihood solution.

(Puneet Kumar Shrivastav is Assistant Director (Faculty) at National Institute of Labour Economics Research and Development, Delhi. Nagendra Kumar Maurya is Assistant Professor, Economics, Department of Applied Economics, University of Lucknow, Lucknow. Views expressed are personal.)